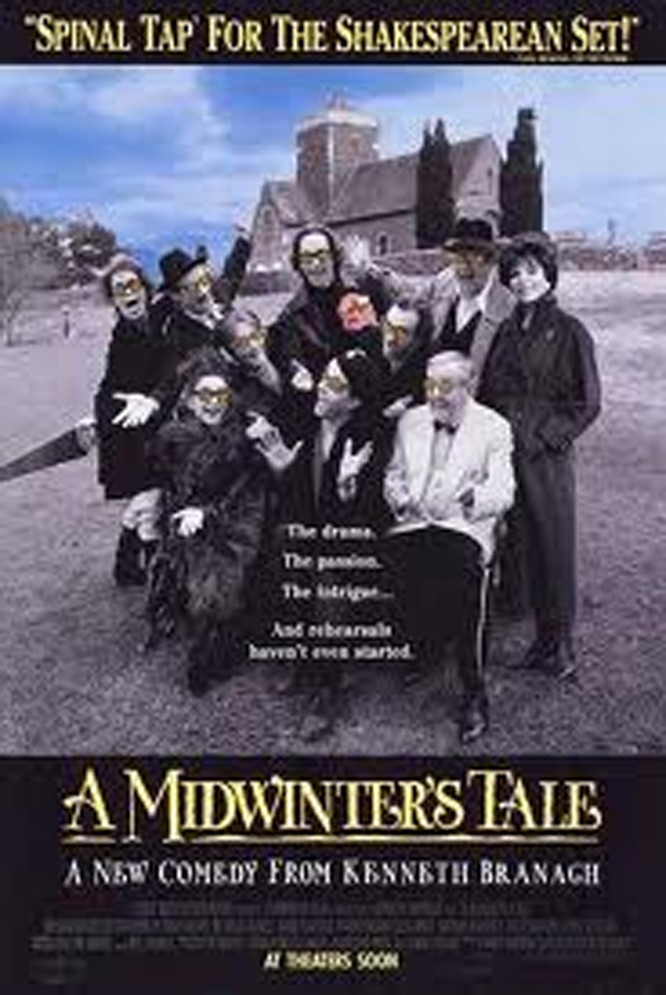

“A Midwinter’s Tale” may not sound like a cheery title for a comedy, but reflect that when I saw the film the first time, at the Venice Film Festival, it was titled “In the Bleak Midwinter.” Nor is the subject matter promising: A poverty-stricken group of has-been and would-be British actors band together to put on a Christmas play in a cold, drafty old church. The play they choose is, somehow inevitably, “Hamlet.” And yet this is the kind of movie you can settle down with.

Populated mostly with unfamiliar faces and photographed in black and white, it’s like one of those 1950s British comedies that assumed the audience was paying attention. It’s about characters and dialogue.

The writer and director, Kenneth Branagh, has toured with his own troupe of Shakespeareans, and so he knows first-hand some of the problems of personality conflict, ego with or without talent, and grim living conditions.

The movie stars Michael Maloney as Joe Harper, an actor who feels he is adrift and must make a dramatic gesture to reclaim his soul. So he determines to put on a holiday production of “Hamlet” in a small provincial town. His agent is played by Joan Collins (somehow my fingers, with minds of their own, continue typing, and spell out “of all people”). She thinks it’s a bad idea. Well, it is.

The broad outlines of this kind of movie have been established ever since Mickey and Judy decided to rent the old barn and put on a show. First there are auditions, at which everyone is spectacularly untalented. The best of the lot are cast in the play, and turn out to be career failures with severe psychological difficulties. They complain about the food, the lodging, and one another. But they all agree the show must go on, and somehow it does, even though the movie’s theme song is Noel Coward’s “Why Must the Show Go On?” Among the members of the cast: a weird production designer (Celie Imrie) who turns the church into an Elsinore that looks, well, exactly like the church looked to begin with. A nearsighted Ophelia (Julia Sawalha) who won’t wear her glasses, and makes her first entrance by falling spread-eagled down the stairs. A Gertrude (John Sessions) played by a drag queen. A Claudius (Richard Briers) who remembers much better days in his career, and is aghast to learn he will share a room with the drag queen, since he hates homosexuals (“The English theater is dominated by the class system and a bunch of Oxbridge homos”). And, of course, the cast drunk (Gerard Horan).

A compulsion that many actors share is the need to say a great many unnecessary words about productions that speak for themselves.

Branagh’s screenplay has fun sending up this tendency. The Laertes (Nicholas Farrell) assures Joe, “Hamlet is Bosnia. Hamlet is me.

Hamlet is this desk. Hamlet is the air. Hamlet is my grandmother!” And an auditioning actor, asked if he can fence, replies, “I live to fence. In a sense, I fence to live.” In the tradition of backstage movies, camaraderie somehow builds among this motley crew, and then, of course, there is a crisis. The crisis is engineered by the Joan Collins character, who is the movie’s one false note. She plays the agent well enough, but would actors at this grubby level be represented by an agent so sleek and glamorous? I envision an agent more along the lines of Zero Mostel in “The Producers.” “A Midwinter’s Tale” is the kind of movie that probably will appeal best to those with a background in the theater and Shakespeare. It asks, but never really answers, the question of why intelligent adults would devote their lives to such an ill-paying, frustrating, disappointing profession. Of course a great many other intelligent adults devote their lives to professions that are equally frustrating and disappointing, and, while they may pay better, are boring, and never have opening nights.