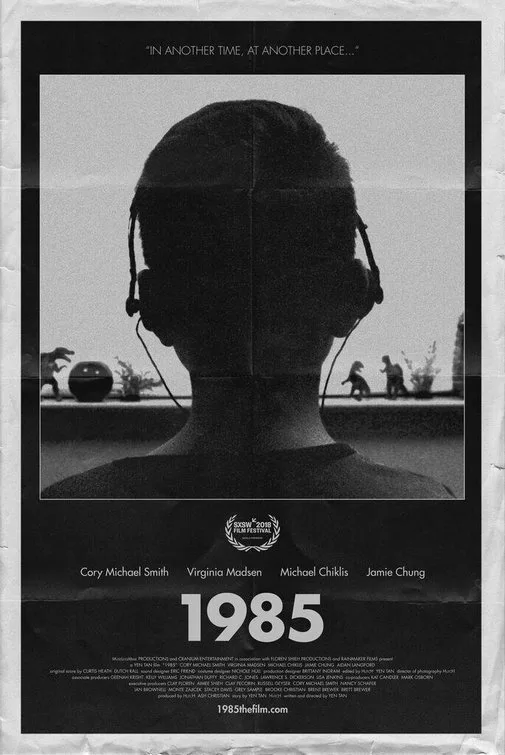

A sensitive drama that slowly builds in power, “1985” feels like a missing minor classic from the decade that preceded the rise of the so-called New Queer Cinema, when independent filmmakers had to struggle to cobble together budgets that let them tell their stories in the form of modest art house movies. Although it builds on decades of similar movies, this tale of a young gay New Yorker (Cory Michael Smith of TV’s “Gotham”) who comes home to North Texas at Christmastime never plays like an exercise in stylistic mimicry. It feels immediate and rings true, thanks to the performances of its lead actors, and the storytelling of director Yen Tan and his co-writer, co-editor, and cinematographer, the single-named Hutch.

Hutch’s Super 16mm photography—with its pointillistic film grain dancing beneath the characters and their environments—instantly situates the viewer in 1985. This is how low-budget art house movies looked in the ’80s and ’90s. The lighting, clothes, and production design all further the sense that we’re seeing a missing artifact from that era—along with 1985 signifiers like Walkmans and synth drums and references to Madonna, The Cure, Ronald Reagan, and Walter Mondale. But the filmmakers’ attention to detail and deep respect for how these specific people would have communicated with each other are what put “1985” over the top. Despite the film’s gay-themed story, its North Texas, working-class-suburban setting, and its constant talk of football and Jesus, the movie it most strongly evokes is “Ordinary People,” a classic about repressed suburban white folks whose social conditioning stopped them from discussing their pain.

Adrian is back home in Fort Worth, Texas, visiting his parents, Dale and Eileen (Michael Chiklis and Virginia Madsen), and his kid brother Andrew (Aiden Langford), a middle schooler. Right away we sense that unspoken tension clouds the family’s ability to communicate. We also deduce that the major characters know more about one another than they let on. There are strong hints that Adrian’s fundamentalist Christian parents know that their eldest son is gay even though they haven’t discussed it with him and are in no hurry to. We sense it in the way that Dale, a Vietnam veteran turned repairman who drives a pickup truck, awkwardly stands next to his son at the airport’s baggage claim area, and in the hopeful, almost pleading way Eileen lights up when Adrian reveals that he’s been hanging out with his high school girlfriend Carly (Jamie Chung), a Korean-American standup comic.

There are intimations that Andrew might be gay, too, and that he senses his own sexual orientation even though he doesn’t have the language (or maybe the courage) to label it. Andrew is initially resentful of Adrian for reneging on an offer to host him in New York—the result of Adrian getting cold feet about the prospect of letting his kid brother see him living as an openly gay man—but he forgives his older brother the minute he starts talking about the new pop music they both love, and that their father has forbidden Andrew to listen to.

A climate of fear and repression clouds the home. Adrian’s family are politically conservative religious people living in North Texas in 1985. They are enamored of a particular view of scripture that’s hostile to anyone who isn’t straight. Their preferred radio station talks of sin, damnation and salvation. Dale’s Christmas gift to Adrian is a new Bible. During a supermarket shopping trip, another high school classmate of Adrian’s who is now an assistant manager follows him outside and offers him a pumpkin pie in order to create an opening to apologize for past bad behavior. We don’t need to hear the specifics to figure out that the classmate was cruel to Adrian for being gay, and feels bad about it now. Like so much in “1985,” this moment shows us the outer edge of a confrontation or epiphany, then lets us fill in the rest with our imaginations, because that’s how almost everybody in this world deals with each other.

The specter of AIDS looms over every scene. Adrian’s lover recently perished of complications from the disease, and there are suggestions (which the film takes its time confirming or denying) that Adrian might’ve contracted it as well. A lot of Dale’s (and to a lesser extent, Eileen’s) discomfort with Adrian can be explained as basic homophobia, inherited from mainstream culture and amplified by their religion and geographic surroundings. But they’re also scared that one of their sons will die from (in their minds) being gay. Their fear and hatred is fused to sincere and abiding love, and this sparks contradictory emotions that they can’t even begin to deal with.

The lead performances are all thoughtful and honest, and Tan’s direction is subtle. Adrian’s drawl becomes more noticeable when he settles back into his old hometown. Dale’s jawline sharpens when Adrian gives the family a series of lavish gifts at Christmas, hoping to prove how happy and comfortable his New York life is, but succeeding mainly in making his father feel poor. The camera keeps zooming into scenes very, very slowly, as if the film doesn’t want its characters to realize that somebody is watching them.

There are perhaps a few too many wordless lyrical interludes, and they go on a shade longer than they needed to in order to make their point—something you could also say about the movie, which is in a hurry not to hurry—but these are small flaws. Each choice, small or large, furthers the film’s story, themes, and sense of life—especially visually. Notice how whenever the characters open up, to the degree that they’re able, Tan and Hutch’s camera keeps its distance for as long as it can, as if to respect their privacy during a difficult time. A trio of intimate conversations between Adrian and Carly is conveyed mainly in medium shots. One of the most wrenching scenes—a backyard heart-to-heart talk between Adrian and Dale, who’s drunk on beer and feeling both sentimental and resentful—spends four minutes framing the characters from head-to-toe before finally jumping into a closeup of Dale. When these characters break down and cry, the sight feels almost obscene, like a form of blasphemy.

Different as they are, Dale, Eileen and Adrian are united by a desire to return to a sentimentalized past that preceded the now. That’s why Eileen’s favorite secret spot to sleep in is Adrian’s impeccably preserved bedroom, the place where she used to read to her sweet son before he hit puberty and started to figure out that he was different from the other boys at school. But you can’t go back. After a certain point, you can’t go forward anymore, either. Which means that the moment that matters most is the moment you’re in, no matter what year it is.