Jeff Shannon, who died Dec. 20, was a Seattle-based film critic and RogerEbert.com contributor who often wrote about issues facing the disabled. He was a gifted writer and fiercely independent man, and his aesthetic opinions often intertwined with his life experience in ways that made him unique, and uniquely important.

As his friend Scott Jordan Harris wrote in an appreciation, Jeff “was more than just a disabled person: he was a disabled activist.” He served on the Washington State Governor’s Committee on Disability Issues and Employment, wrote widely about his experience as a disabled person, and often wove political analysis into his film writing.

One example is Jeff’s 2011 review for RogerEbert.com of the documentary “Life is Worth Living,” which mixed biographical nuggets (“I had just turned 29 and I’d been disabled (C-5/6 quadriplegia) for 11 years, since a diving accident on the coast of Maui in 1979, two weeks after high-school graduation and three weeks before my 18th birthday”) with critical appreciation of a documentary about the history of disabled activism in the United States. The piece includes a sharp assessment of what the landmark 1990 Americans with Disabilities act has accomplished and where it has fallen short. “To be disabled in America, in 2011, is to realize that you may have gained your civil rights, but most of society didn’t get the memo,” he wrote.

Jeff died yesterday at Stevens-Swedish hospital in Edmonds. He’d been on life support due to pneumonia, which made it hard for his heart to process oxygen without assistance. He is survived by family and friends who remember his humor, compassion, and determination to make a difference. You could see this quality manifested not just in his political activism and straightforwardly prescriptive writing—for New Mobility, and more recently for FacingDisability.com— but also in his reviews and features. Jeff’s life experience let him speak with authority on subjects that other writers might have had to imagine their way into.

One example is Jeff’s writing about “Million Dollar Baby,” which he loved and defended, both on his own and in concert with Roger Ebert, who loved Jeff and promoted his work for years. Jeff was angered by conservative activists who blasted the Clint Eastwood film as an ad for euthanasia. He reached out to Roger and praised it.

“Until ‘Million Dollar Baby’ become an issue,” Roger wrote in a 2005 piece, “I didn’t know he was a quadriplegic. He is writing an article about the movie from his point of view; he thinks it is a great film and takes issue with those in the disabled community who attack it. Shannon has chosen life, and leads a full and productive one. Ramon Sampedro, the character in ‘The Sea Inside,’ refuses to be supplied with a chair he could control by his head and breath. He has given up. Jeff Shannon wrote me about the movie: ‘Despite considerable pain and anguish for a variety of quad-related reasons, I agree with Ramon Sampedro’s cause, but I cannot share his attitude for one simple reason: I look at life the way I look at a good movie — I can’t wait to see what happens next.'”

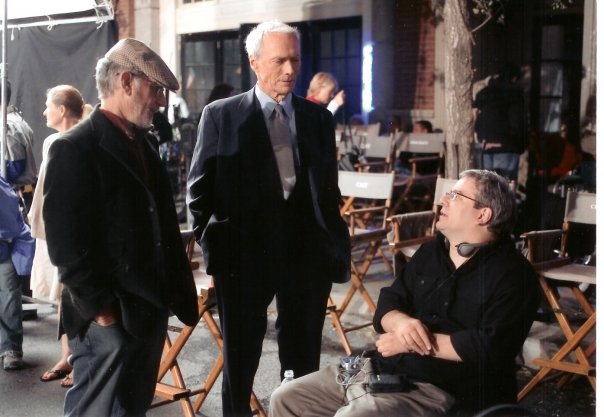

Jeff’s personal authority allowed him to play devil’s advocate and ask knowledgable and pointed questions of Clint Eastwood during an interview about “Million Dollar Baby.” “Some disabled people are very discouraged by the film,” Jeff told Eastwood, “because they perceive a potentially harmful image that suggests that disabled people are ‘better off dead.’ “I don’t think that’s the situation [in the film], and it wasn’t the intention at all,” Eastwood replied. “The intention was just to tell the story of these two people, and it’s not advocating that at all.” Eastwood was so impressed by Jeff that he invited him the set of his next film, the Steven Spielberg-produced “Flags of Our Fathers,” where the photo at the top of this article was taken.

Most of all, though, Jeff leaves behind a legacy of friendship.

“I met Jeff when I arrived for a party and found him outside, freezing, unable to reach the doorbell or, for that matter, the door to the host’s house (stairs!),” Seattle-based journalist Christy Karras wrote me. “Once we got that sorted, I spent a fair amount of time that evening talking to Jeff about our common interests – film, music, politics. We remained friends, mostly online but occasionally in person. He, my husband Bill and I went together to a Prince concert a couple years back. Jeff wasn’t feeling very well and wasn’t sure he’d be able to drive, so we drove to Tacoma with him in his van. We had to argue with ushers in order to make them let us sit near him so we could keep an eye on him. He taught me a lot about what it meant to be a person with a disability, and I’m grateful for both his work on behalf of others with the same issues and his patient willingness to educate the rest of us.

But mostly, I’m grateful that he let me into his wide and interesting group of friends, some of whom only knew him through the magic of the internet.”

She continues, “What happened to Jeff really could have happened to any of us, and I’ve thought about that a lot. I was happy when he started writing for the Ebert blog, because if anyone could understand the shit sandwich (my husband’s words) Jeff was dealt, it was Roger Ebert. And Ebert could understand Jeff’s love of film…but also of philosophy and culture and life in general. I like to think the two of them have found each other again.”

RogerEbert.com contributor Edward Copeland, a dear friend of this author, was one of many people who shared an experiential as well as emotional bond with Jeff. Edward has been bedridden with primary progressive multiple sclerosis since 2008.

Today Ed wrote me, “I wish my friendship with Jeff Shannon started long before it did and, with the sad news of his death Friday, I desire more than anything that our relationship could continue. Another much-missed mutual friend of Jeff and myself, Roger Ebert, brought us into each other’s orbit of the blogosphere when Roger promoted reviews we’d each written of the great documentary ‘How to Die in Oregon,’ dealing with the Death with Dignity law in the title state and the fight to eventually legalize it in Washington state as well. Our perspectives on the film came from far more personal places.

“Jeff amazed and inspired me. Being able to drive a car until recently; living by himself with just visits from caregivers for a few hours on certain days; getting out to do things with friends, such as see movies and write about them; fixing up snacks in a nearby microwave and delivering them to himself as we chatted on the phone. What I’ll treasure most are our phone conversations where we’d share useful information in terms of health care ideas to suggest to doctors, and services to use to help defray costs and for other means.

“In our final email exchanges, he apologized for not returning a phone message, particularly since he was concerned about me checking myself out of a hospital. I reassured him he’d understand when I got to tell him the story, but unfortunately that opportunity passed, as he wrote that he had a bad cold and couldn’t really talk on the phone. This led to me being the worried one. His last email told me that he was in a clinic awaiting chest x-rays because he thought he had pneumonia. He wrote, ‘What a fine pair we make, eh?’ True, but I don’t relish that I’m now a solo act.

“Farewell my dear friend. Our friendship ended far too abruptly.”