“There ain’t no countries anymore,” a revolutionary leader tells the two buddy heroes of John Carpenter’s “They Live.” It’s a sentiment that echoes the second-most famous monologue in Paddy Chayefsky and Sidney Lumet’s 1976 media satire “Network,” from the scene where network boss Arthur Jensen (Ned Beatty) tries to scare prophet-of-the-airwaves Howard Beale into toeing the line. “You are an old man who thinks in terms of nations and peoples,” he says. “There

are no nations. There are no peoples. There are no Russians. There are

no Arabs. There are no third worlds. There is no West! There is only one

holistic system of systems, one vast and immane, interwoven,

interacting, multi-variate, multi-national dominion of dollars!”

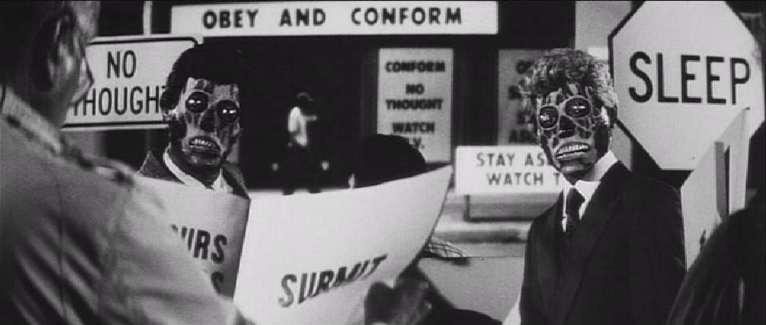

That’s what Roddy Piper’s unemployed drifter John Nada learns in “They Live” after he puts on a pair of sunglasses created by rebels who are trying to wake the sheeple up to the reality of the holistic system of systems, the multi-national—in reality extraterrestrial—dominion, which is run by otherworldly colonizers who look like bug-eyed, skinless humans. What he’s really seeing is the desperate underbelly of Ronald Reagan’s vision of “Morning in America”—a post-Vietnam, happy-gas exhortation quoted by one of the aliens in “They Live.” The rich are getting richer. The middle class is increasingly unemployed and stressed-out. The jobless, poor and infirm are out on the street, or else stuck in a “Hooverville”-type camp—like the one John settles in, and that is destroyed by police tactical units and bulldozers once authorities realize that there are revolutionaries hiding among the displaced. “They’re free enterprise,” says Gilbert (Peter Jason), the same guy warns John and his pal Frank Armitage (Keith David) about the conspiracy. “To them we’re just another developing planet…their Third World.” Billboards and magazine ads and TV commercials that seem to be selling specific products or services bear subliminal messages, in simple black type on white, ordering us to “Obey” and “Consume” and “Marry and Reproduce” and “Watch TV.”

John, who relocated to Los Angeles after the economy in his hometown of Denver collapsed, never considered the possibility that there might actually be an organized conspiracy to exploit working people, anesthetize their brains with tabloid culture and mindless, repetitive TV programs, and systematically rob them of their postwar standard of living, all while promulgating the “level playing field” and “up by your own bootstraps” messages drilled into Americans from birth and repeated by their politics and culture. But those sunglasses glasses reveal the truth—and how appropriate that the film would portray this hidden, horrible reality as black-and-white. There is no subtlety in the movie, no gradations of “color” in its message. It’s the ultimate tinfoil hat film; not since “Close Encounters” had an American studio picture so enthusiastically validated the notion that a seemingly insane hero might be seeing a reality that others either cannot see or have chosen to embrace.

Most of the cops in the film are human; some are aware of the conspiracy and most aren’t, but they’re all part of it. And there are Vichy-type collaborators everywhere, people who’ve decided to walk that “white line” that Frank Armitage speaks of. This character—named for the screenwriter, who is really Carpenter working under a pen name—is a warm and genial version of the “Good American” who just wants to keep his head down and get paid. It’s he that John concentrates on converting, perhaps remembering an early conversation where Frank talks about how the system is rigged against guys like him and John, because “he who has the gold makes the rules.” John succeeds in the film’s most famous setpiece, and the funniest thing in the movie besides the hero’s final bird-flip: a seemingly endless brawl in an alley that finds Frank pounding John into submission, then stumbling away without having donned the glasses, only to have his bleeding adversary come crawling or staggering after him, gasping, “Put the glasses…ON!”

Carpenter typically presents evil as quiet, implacable and vague, and has it shamble or walk slowly rather than run, as if it knows you can’t get away no matter how hard you try. Think of the murderer in “Halloween,” the vengeful ghosts in “The Fog” or the Satanically attuned masses drawn to skid row in “Prince of Darkness.” In “They Live,” it’s the police who are portrayed that way. Carpenter films them in what amounts to an inversion of the way he photographed the rotting lepers inching through blue mist in “The Fog.” The police move towards revolutionaries and bystanders in a human wall formation. They’re shrouded in fog from the tear gas they triggered. The lighting is hellish red.

Carpenter based “They Live” on a mid-’80s comic-book version of a 1968 short story by Ray Nelson, “Eight O’Clock in the Morning.” He has said that the political satire wasn’t there in the original; Carpenter added it as a response to the way American politics and culture changed in the ’80s, becoming more openly acquisitive and hateful under Reagan, who broke the backs of the unions and rolled back a lot of the economic reforms put in place by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Carpenter always had counterculture leanings, but they weren’t expressed as obviously as in films by his colleague and friend George Romero (both of whom are name-checked in the “Hey, what’s wrong, baby?” gag). Here he made what may be the most unabashedly counterculture-left studio picture of the 80s not directed by Oliver Stone. The movie is propaganda, more accurately counter-propaganda. Carpenter later said he hoped it would influence the 1988 presidential election, but even if it had been released earlier (“They Live” came out on Nov. 4, the election was Nov. 8) it might not have had any impact. Voters installed another Republican, George H.W. Bush, as president after eight years of Reagan; the movie bombed. Late-eighties movies that amplified the messages Carpenter found grotesque—like “Secret of My Success,” “Working Girl” and “Cocktail”—were hits.

“They Live” is one of Carpenter’s oddest and most distinctive works, not just because of its overt political messages or the fact that it’s basically a comedy, but because it simultaneously invokes a tradition of more realistic soclal problem-driven fable movies, like “Sullivan’s Travels” and John Ford’s big screen version of “The Grapes of Wrath.” As his name suggests, John Nada—is his full name even spoken?—is as much an iconic blank slate Everyman as the characters that appear in the “parable” sections of Steinbeck’s novel. But he doesn’t suffer silently or lash out impotently; he gets himself a police shotgun and announces that he’s here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and he’s all out of bubblegum. In the bank shootout, especially, “They Live” asserts itself as a consummate tinfoil hat film; every few days in this country there’s a shooting incident in a public or quasi-public place, and sometimes the shooter claims to have been trying to send a message, usually a nonsensical and deranged one, but here we cheer for the gunman because we’re seeing the world through his eyes.

If you show this film to young viewers, you might have to explain “Morning in America” and “trickle-down economics” and perhaps some basic Marxist concepts to get across exactly what made this film so surprising at the time. You might also brace yourself to expect laughter at how “primitive” certain features of 1988 American life now seem. There’s no Internet, no smart phones, and the police (aided by tiny hovering camera-bots that are like today’s drones) have to look hard to find their prey. And television is portrayed as a monolithic, bland evil, as it tended to be in 1970s and ’80s films by directors like Carpenter and David Cronenberg; today, television is a thing you can watch on a computer or a phone, not a squarish box that people stare into for hours on end, and the idea of entirely disabling an enemy’s ability to broadcast mind-controlling propaganda by taking out one transmitter seems quaint in an era of atomized data and asymmetrical warfare.

But these and other culture-technological details aren’t terribly important, ultimately. Look at the police marching ominously forward, clunking their batons and raising their firearms, and you see Ferguson, Missouri. Listen to the rants about how we’re all just cattle to be bred and slaughtered by the elites, and about how there is really no government anymore, only “owners,” and you’ll feel like you’re Twitter or Facebook. In all the superficial ways, this is a dated movie. Put the sunglasses on and you realize it hasn’t aged a day.