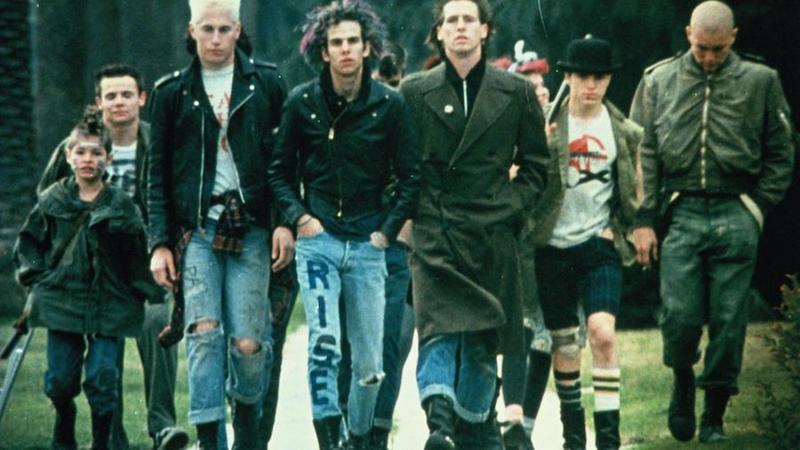

For many film buffs, filmmaker Penelope Spheeris will always either be The Punk Lady or the “Wayne’s World” Woman. Honestly: she’s both, and so much more. Spheeris—who wore several hats while working on short films written by and starring Albert Brooks and Richard Pryor—has more than earned her reputation as a big-hearted, but un-sentimental “rock ‘n roll anthropologist.” The humor in her movies—whether it’s the essential punk rock doc “The Decline of Western Civilization” or her irresistible 1994 homage to “The Little Rascals”—stems from her clear-eyed understanding of her characters, many of whom participate and re-establish a boy’s club-style society. Spheeris’s versatility as a filmmaker therefore arises from her consummate patience and humane love for all of her characters, especially the cruel ones.

I spoke with Spheeris this past January, a month that reminded me, in a couple of ways, why I love her films. On January 14th, I raced to buy Universal’s new blu-ray of Spheeris’s “The Little Rascals.” And on January 16th—upon hearing about the untimely death of Lorna Doom, the bassist for California punk group The Germs—I overturned my cluttered apartment to find my copy of Spheeris’s “The Decline of Western Civilization,” which features amazing concert footage of Doom and her band. Finally, I spoke with Spheeris last week, after reading that Shout Factory is releasing a blu-ray of her caustic punk melodrama “Suburbia” on January 29th. This is the third time I’ve interviewed Spheeris; each conversation reveals something new and hilarious about her and her work. This time around, we talked about working with child actors, directing Donald Trump, filming the recently-deceased Germs bassist Lorna Doom, and letting Motley Crue bassist Nikki Sixx date her daughter.

The thing that makes “Suburbia” and “The Little Rascals” feel like “Penelope Spheeris movies” to me is the way that you show an overwhelming sense of empathy for your young characters. It’s a very unsentimental love, one that seems to come from your need to understand where these characters are coming from. I have to ask: when you watch kids’ movies—do you ever get frustrated that they don’t really get the way that teenagers or pre-teens talk to each other or think?

I think what you’re asking is that you sense a feeling of compassion from me, as a director, toward teenagers and kids.

Yes.

That’s definitely true. I think it’s probably my way of trying to embrace my own horrific upbringing– not embrace it, but make it right. The last part of your question was what, do I get frustrated because teenagers today don’t get it?

No, just the way that they’re portrayed in movies and TV shows.

I have to make a huge confession: I became so frustrated in trying to find a good movie that I kind of gave up over the last five years…and so therefore, I very seldom watch movies anymore. Isn’t that crazy?

That makes me a little sad, mostly because that’s one of the reasons I wanted to do this interview: I selfishly want more Penelope Spheeris comedies and dramas. They’re the best!

Thank you so much, you’re so sweet. Not watching them and not making them are two different things. Just because I don’t watch them doesn’t mean I won’t make them.

Good.

Thank you for asking that. But the quality of films anymore and the way they’re made and the way that the studios…and the big TV distributors treat not just me and the directors, but the crews and everything else…it’s hard to be a part of it, you know? Movies come out so bad. I haven’t seen one movie this year. Can you believe it?

Jeez. I mean, my problem is. because I am so invested in this stuff—partly for professional reasons—but I’m just so invested in this stuff that my first instinct is to say, “Well, there’s this, that, and the other thing!” But I get what you mean.

(Laughs) Well tell me, because if there’s something worth watching, I want to! My god – I’ve always had a hard time looking at films in the first place although I used to see every single one. I was there at the opening of “Mommie Dearest” at the Chinese Theater at noon! I had to see every single film, you know? But there came a time now where I’ll start watching a movie and I’ll be like, “Oh my god, I can’t even get through it!” But I like to take suggestions from people and if I get enough suggestions about the same film, then yeah, I’ll check it out! It’s a terrible confession to make. The other thing is: I think it adversely affects my creativity to get too many bad movies in my head, you know?

That makes sense. There’s so much cliché…I get that. I think I get that.

My sister works a lot in television because she’s a set decorator, and I’m telling you, at least twice a week she says to me, “OMG, you’re so lucky you’re not doing this. There’s no money, there’s no time, everybody’s grumpy because they are making no money, and have no time.” And I mean, look, I feel like I’m being so negative in this conversation and I apologize for that, but I also feel like I just need to state how I feel, and also how a lot of my contemporary friends—people my age—feel these days about the state of the movie business and even TV. It’s just…I don’t care anymore, you know?

Totally fair. With that said: the difficulty that comes with making a movie that’s both a commercial and artistic success—that is, indirectly, why I wanted to talk about “Suburbia.” Because with “Suburbia”—and even before that: you were told, before you made “The Decline of Western Civilization,” that to make a popular film you had to make a fiction film, not a documentary. And when you did “Suburbia,” Roger Corman told you that your film had to have sex or violence every 10 minutes. How did you negotiate what you want to put in the film with that sort of P.T. Barnum mandate?

I wasn’t happy with that, but I was at least aware enough to know that if I didn’t do what he asked, that he would either do it anyway or tell me to go away. And mind you, that was at a point in my career where I really did want to establish myself as a narrative director. I mean, I had done “The Decline of Western Civilization,” and it was the most written-about film of that year. But that’s because nobody understood punk rock. Still, I really, I wanted to do narrative pictures, so I had to do what [Roger Corman] said. So I reluctantly had that scene where the girl gets her clothes torn off. And I reluctantly killed the little girl—very badly, by the way—with the dolls at the beginning of “Suburbia.” I did that, you know? I also knew: in order to keep going as a director, I had to do what he asked me to do!

Which is funny, because the hardest scene to watch in “Suburbia” is one that I’m 100% sure is all you—and it’s one that’s not explicitly violent. It’s where Sheila talks about how she’s almost raped by her abusive dad, and the response she gets is, “That’s what I thought you were going to say.” Is it fair to say it was easier for fellow punks to believe stories of parental abuse…easier to believe than adults, that is?

Well, back then, you didn’t go to jail for abuse. Now you do! When I was growing up, I wasn’t sexually abused, but I was extremely physically abused. So when I wrote “Suburbia,” I took stories of my own and integrated them with stories of the punk kids that I knew, and sort of merged them together to tell stories of these kids’ lives. I don’t know if you read this anywhere or not—because I’ve told other people—but the scene where they bring Sheila’s body back to her father? That happened to Darby Crash’s mother, because Darby’s brother OD’d.

God, that’s right, I did read that…

I took a lot of…actually, most of the situation I took from real life. Even those dogs that were let loose: that was a story in the newspaper.

For me, the most remarkable thing about “Suburbia” is that you’re able to take those stories and get these kids to convey them in a way that feels authentic. It feels like this is their story. I wonder in that sense, how tough was it to earn these kids’ trust and tell them: “Here’s the scenario, here are these deeply personal stories, hit your marks, go for it.”

I think the reason that they did, so generously, offer me their trust was because of “Decline.” I had a lot of credibility with punk kids after doing that movie. Because back then, punks were portrayed in an almost comic fashion; people didn’t understand them. So I think I was able to get performances out of these real-life punks because they trusted me. But I had to really argue with [Roger Corman] about being able to cast them; he didn’t understand punk rock either, you know what I mean? He was like, “Well, you gotta have real actors! You can’t just have these people!” and I was like, “Well, you used real Hell’s Angels in ‘The Wild Angels!’ You used real bikers!” And he goes, “Oh yeah. Well, that worked.” (Laughs) I remember me and the other producer taking Roger out to dinner at Spago after the movie was over, and I said to him, “Let me tell you the biggest new trend there is: rap music.” And Roger looked at me and tilted his head and goes, “Rap? Like, how do you spell ‘rap?’ What is that?” (Laughs)

One of my favorite scenes in “Suburbia” is the one with a very non-professional actor who’s famous now: Flea. It’s the bit at the convenience store where he pours that blue slushee in the jar of pickled eggs. That scene not only seems Corman-friendly, but is very character-driven. It’s that unsentimental quality we were talking about earlier: these kids go off on that convenience store clerk just because they don’t like what they’re hearing, or maybe even the tone of what they’re hearing. How hard was it to get them to act out on camera? That scene is not exactly flattering to them!

Well, first of all I was starting with a good, natural actor with Flea. Like, the moment I set eyes on him when he was 19 years old at Lee Ving’s house, I was like, “That kid’s a star.” I was right on a lot of different levels there. And Flea is just…I love him because the camera either—well, maybe I made this up—but the camera either loves you, doesn’t care, or doesn’t like you. OK? And with Flea, the camera loves him. You can’t go wrong. Maybe he mugs a little bit, but he’s just so damn cute with the split in his teeth and everything! Also: I didn’t tell him, “Oh Flea, put the rat down your throat!”

Right!

I didn’t ask him to do that, you know? Even though he doesn’t admit it, he truly is a punk rocker at heart. He likes to think he evolved beyond that, but you know what he says? He says that when he travels on tour with the Peppers, everywhere he goes, even in the most obscure countries, punks come up to him and say that “Suburbia” is the punk rock bible.

“Suburbia” is great, not only during the big emotional moments, but it’s got…I think the response you’re talking about is definitely at least partly because of these very little mood-driven scenes, like the bit where—and I think it’s also one of your favorite scenes, too—where the girls are talking to each other, and they go “Guess what? Chicken butt.”

(Laughs) I know! We’d been saying that for years! Not to compliment myself, because I didn’t notice it at the time. But for years now, people have been saying that scene where Skinner realizes that Sheila is dead, you know when he busts up the mirror? He did all that himself. I just kept the camera running and without saying a word, he expressed so much emotion. I’m just proud that these kids could do that. I mean, I feel like doing a “Suburbia” remake, I guess you’d call it. And I could probably do that, because the homeless situation here, especially in California, has gotten so crazy and out of control. Those kids were homeless back when I made “Suburbia”; they were squatters. They may have chosen to be homeless, some of them, but they were homeless, and it makes a comment about homeless people forming new families. That’s what I like about it and that’s what “The Decline of Western Civilization III” is about, too.

Your work with kids is so good, and it isn’t surprising that it’s so good since you and your daughter, Anna Fox, make such a good team. I know she was pretty instrumental in the restoration of the “Decline” trilogy. She also helped you book some of the bands for “The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years,” back when she was a teenager. There’s one story that’s always made me laugh…and if you don’t want to talk about it, I totally get it. But: I read that your daughter briefly dated Nikki Sixx—but it was only after you talked with him. I always wanted to know: what was that conversation like?

Oh, it was horrendous! She was like, 17 (which is underage obviously.) I kind of did a calculation the other day, because there was something on the news recently about Nikki having a baby with his new wife; I don’t know what number wife that one is. So he now has a brand new baby girl, and I think he has like two or three other girls. I often think: what is he doing now when somebody like him—the equivalent of him today—wants to go date one of his 17-year-old daughters? What does he do? Yeah, he got his karma back. (Laughs) But what happened with Anna and Nikki was: she said that he had asked her out, and I said, “Well, you know the rules. The rules are: if you’re going to go out with someone, I need to meet them. I need to know their name.” They didn’t have cell phones back then, but still: “I need to know how to reach this guy if I can’t find you.” So Nikki Sixx pulls up to my house in a stretch limo. He gets out of the car, and he’s wearing a black rubber catsuit or whatever the hell it was. And his hair’s sticking up a foot high.

Have you never read this story? This is hilarious. He sits on the sofa there and he says, “I don’t like something you said about me.”

I said, “What?”

And he said, “I don’t like that you said you didn’t want your daughter to go out with a 40-year-old heroin addict.”

And I said, “Oh, I’m so sorry: how old are you?”

(Laughter) Oh wow!

“I’m sorry if I got your age wrong, but—the other part is true, dude!”

Oh my god! Oh wow.

Anna went out with Nikki, but she couldn’t get into clubs. So she had to sit back in the limo, and wait for him to go party. It was such a great life lesson for her.

That’s amazing. Let’s fast forward to “The Little Rascals” though. That’s obviously a completely different project, not just in terms of the different tone, but also because there is an age difference between the kids in “Suburbia” and “The Little Rascals.” Those were young kids, even younger than the studio executives at Universal wanted. You kind of had to argue that…I love that you made a very studio-friendly argument with the studio executives: “If you want a sequel, these kids should be younger than nine.” Why seven year-olds?

When I first got connected over at Universal: there was no script. They just said they wanted to do…well, I’ll back up even more, just because I think it’s kind of interesting, and I’ve never really told people this. After I did “Wayne’s World” at Paramount, they wanted me to do “The Brady Bunch.” I did not know the “Brady Bunch” TV show very well so I said, “I can’t. I don’t know it well enough and I’m not interested in it, so no.” Then I was asked to do “The Little Rascals,” and I said, “Now that I’m interested in, because I know it by heart.” That’s why I did “The Little Rascals.”

But when I went over to Universal, there was no script. So I had to start from scratch and they said they wanted Steven Spielberg as the executive producer on it. But he didn’t want to do it. I said, “Well, that’s fine with me. Let me write the script.” So I wrote the script, they showed him the script, and after he read it Steven wanted to do it! Thanks a lot, dude! (Laughs) Anyway, it turned out he was such a pleasure, honestly. And I’m not bullshitting. He said to me, “Working with these children is going to be one of the best experiences of your life.” And I thought, “Right, dude, sure.” (Laughs) And he was right! My rule when I shot that film was that when the kids came on set, I gave a hug to every kid, every day!

Oh my god.

I know! So with the clubhouse scenes I’m like, “Oh, Jesus Christ, I’m on number 35 with the hugs,” you know? (Laughs) But it did put everybody in a really good mood! And seven year-old kids still have one foot in heaven, you know? They’re just all good, so when you’re around that, you feel that way, too. There was not one time on that shoot where any of these kids were a bummer. The only thing they did is they’d forget they were being filmed, and kind of walk off-camera! “Oh, there’s a butterfly! Lemme go get that!” You know? So oftentimes we had to have the [first assistant director] hold the kids’ feet underneath the camera frame, so the kids couldn’t move. That was the only little issue there. But for the most part: it was a total pleasure.

The thing you’re talking about, in working with these untrained actors: the difficulty in nailing a scene like the one where Porky and Buckwheat chase that duck with a buck…the difficulty seems to come not only from your knowledge and love of the source material, but also your love and patience for these non-professional actors. I love the fact that in the end credits, you show us some of the miscues you just talked about, the staring-at-the-camera stuff.

Oh my god: “Sweety, don’t look at the camera!” I know! You know why they did that? This is a good one: kids like to look in the lens to see themselves! They are these big Panavision lenses that are five inches across, so they like to look in there and see themselves! I could never get them to get their screen direction look correct because they’d look in the camera, so what I did was I asked the prop department to get me a mirror. And wherever I wanted the kids to look, I’d put the mirror. So they looked at that, and I got the screen direction right.

I read that there were a bunch of crew members who were kind of pissed off about having to constantly do repeat takes for these kids. Is that true, or even fair?

I don’t know, I don’t remember that. I didn’t…I didn’t ever get those complaints directly. But I’ll tell you one thing: that film had to be shot in tiny little pieces. That was shot on film, and some of the pieces of film were three feet long, little tiny pieces because I had to figure out how to put it all together. Casey Silver, the head of the studio, was looking at dailies, and said, “There’s no way in hell this is going to cut together.”

And I said, “Yes it will, because I know the pieces.” I’ve got that kind of brain where I can just remember where every little piece goes.

And he said, “Prove it.”

And I’m like, “Oh, you’re breaking the [Director’s Guild of America] rules, man! You can’t ask me to give you a cut before 10 weeks! But I’ll do it just to show you that it works.” And I cut it together, and it worked.

And he was like, “Sorry, keep going!”

There were also reviewers who, in 1994, watched the film, and complained that it was too “vulgar.” Which is striking, because you nail the tone of the Hal Roach-produced “Our Gang” shorts! You get everything: Alfalfa’s cowlick, Petey peeing on the fire, Buckwheat joking about catching “a big fat one”…it’s all there, all from the shorts.

Yeah. I think the original Rascals were successful on TV—and in theaters, when they’d run them as shorts—because they were like real kids, and real kids are not polite a lot of the time! So for that reason, I think it kind of did hit home. You look at what kids do today and you say, “Good lord.” Compared to today they’re like angels!

I also don’t find being called “vulgar” to be an insult, actually: I take that as a compliment.

By the way: did you remember that Donald Trump is in the movie?

Yes. There’s that great outtake where he’s being an utter shit. I love those!

Are there outtakes of Trump?

Yeah! There’s a bit where he spits out something and it’s like, “Oh, we’re still rolling?”

Yeah, like peanuts or popcorn!

“That is bad popcorn!”

Yeah, well, I had no idea I would be directing a future President at that point! I’m sure he didn’t either!

Exactly. Speaking of toxic masculinity: I wondered—because I know that including and emphasizing the He-Man Woman Haters Club as a prominent part of the film story was your idea. That literal boys’ club mentality is the subject, in a sense, of a lot of your movies.

Well, there was a He-Man Woman Haters Club in the original “Our Gang” shorts.

Right, but in interviews, you said that it was your idea to make the club the film’s focus. I think you said that you wanted to give the film “an issue.”

Well, I don’t know. I mean, as many times as I wanted to jump onto the #MeToo flurry…I mean, I’ve got stories you wouldn’t believe. But I’ve just seen the damn thing backfire so many times! And I’m sensitive to stuff like that, you know? I don’t know how some of these actors can just let it roll off their backs. Because if somebody criticizes me for something, I lose sleep over it, you know? Also: I could be impulsive. I don’t do Ambien, OK, but I could. And I could do a Roseanne thing impulsively, and realize it was a stupid idea later! So I don’t do any of that shit, you know?

But before I die, I’m going to write that book that tells all those stories about the way I was treated when I was coming up in this business – and it’s ugly. I don’t mean necessarily on a sexual level (well, one time). But most of the time, on an emotional torture level, especially with Bob and Harvey Weinstein. I was a little too old for Harvey to have assaulted me, if he did assault women. But the mental and emotional torture I went through with Bob was unbelievable. I’ll give you a quote on the movie “Senseless.” I was arguing with Bob, because he kept rewriting the script, and screwing the whole thing up. And I told him: “This scene doesn’t belong in there!”

And here’s a quote from Bob: “It’s my fucking money and I’ll spend it any fucking way I want!”

Jesus.

Yeah. How are you gonna argue with that?

I mean, I imagine that you can’t.

No. Because it’s like arguing with a brick wall with those guys, you know? It’s their way or the highway.

Still: the boys’ club was, as you said before, an “issue” for your “Little Rascals” film. I was never sure if that was a joke or not, because it is true on a basic level. That is the plot of the movie. At the same time, you treat that theme very lightly. You’re an anthropologist first, and then a satirist.

The reason I wanted to put that in the movie is so the boys could learn a lesson. Although it seems like the boys were just bad, bad boys, because they did that stuff. But that’s not completely true. These boys are OK, because they learn that hating women is not the right thing to do. I think that came through in the film. But like I said, it would be very interesting…they did a DVD remake of my film recently. I don’t know how it did or anything, because they refused to send me statements for my participation. So I don’t know how that remake did. But I would bet that the He-Man Woman Haters’ Club is not in there, because you can’t do that stuff anymore without somebody getting all over you and saying that you’re a sexist, you know?

Really?

I know! It’s just crazy.

The other reason I wanted to talk now is because of the recent passing of Lorna Doom. I hate saying “passing” because it’s weirdly disrespectful. But she died recently, and I was just rewatching the first “Decline,” looking for her in the Germs footage. I saw her performing “Manimal,” and “Lexicon Devil,” things like that. I guess the simplest way to ask this is: what was it like to film Lorna for that movie?

Honestly, she was one of the most elegant, mysterious, and I don’t know, just sort of confident—without ever being arrogant—women I’ve ever known. I really had a lot of respect for her, but along with being confident and elegant, she was also very private, and she was never very forthcoming. I think as you see in the film, in terms of just sitting around chatting: she often didn’t stay a word. In one scene, she’s holding [“G.I.”], the Germs album. I remember asking her questions, but she would just shake and nod her head: “Yes or no, yes or no.” I think she was very shy. I didn’t know her all that well, just because she had very few close friends, and I wasn’t one of them. But I did have a great deal of respect for her.

And the other thing is: she was probably, in that whole punk scene, one of the most gorgeous, beautiful women. Her face was absolutely perfect. She could have been a model or something, you know? And she always had the best, what should I say, style. The way she dressed, every time you’d see her at the club you’d go, “Oh, look at that! She sprayed her cowboy boots green! I need to do that! She put this kind of thing on her jacket and I need to do that!” She was a trend-setter and a very, very nice person. She never had any negative vibes.

I love that you said “mysterious” and “confident.” Just watching her perform “Lexicon Devil”– which is not in the film, but is included on the blu-ray as a bonus feature…just the way Darby goes over to Lorna, and talks with her before they start the performance. And the way she smiles at some of his acting out while he’s performing. Your footage really seems to capture exactly what you saw because that footage is like…that’s her, on stage, writ large.

Well, before she passed away, I was going to say maybe a year or two ago it had crossed my mind that I wanted to reach out to her, not for any sort of interview or any of that kind of reason, just more “Hello, how are you?”

And I decided not to try to find her, even though I knew how to. Because I just felt she would probably be as closed-off as she always was, you know? I don’t know. I mean, it’s very, very sad that she…was she 60 or something like that? Do you know how old she was?

Not offhand, but let me check.

She was older than I thought.

61.

61, yeah. She must’ve been a little older than Darby, because Darby was a kid. He was like 20 or something when I shot him.