In honor of Roger’s birthday on June 18th, we will be republishing some of his classic articles throughout the week. Paul McCartney was born on the same day and in the same year as Roger, yet I wasn’t aware of this interview until one of our readers, Ramin Serry, mentioned it online. It was originally published on October 21st, 1984.—Chaz Ebert

Roger Ebert Interviews Paul McCartney (October 21st, 1984)

IT WAS LIKE A SCENE out of one of those movies where the crazy teenagers are trying to break into the Beatles’ hotel. I had made my way past the security guards in the lobby, and the crowds of fans with autograph books, and the stern-faced hotel assistant managers, and now here I was, alone in Paul McCartney’s suite at the Ritz-Carlton! This was the big time. Maybe I could sell the pillowcases as souvenirs.

The phone rang. I hesitated a second. Should I answer it? What if it was a female voice offering me unspeakable favors in return for the key to the room? I picked up the phone. It was my editor, who is a Beatles fan. “I have a question for you to ask Paul McCartney,” he said. “Ask him why his music has been really lousy for the last couple of years.”

I hung up the phone. Larry Dieckhaus, the man from 20th Century-Fox came into the room. I told him it was a strange sensation, for anyone who grew up with the Beatles, to actually be in Paul McCartney’s hotel room. I’ve interviewed John Wayne and I’ve interviewed Sophia Loren, I said, but this is a Beatle.

“This isn’t actually Paul’s room,” Dieckhaus said. “We told everybody he was at the Ritz-Carlton, and then they booked a floor at the Ambassador East and put him over there, to throw off all the fans. Then he comes over here for the interviews. This is all a little amazing. It’s like Michael Jackson.”

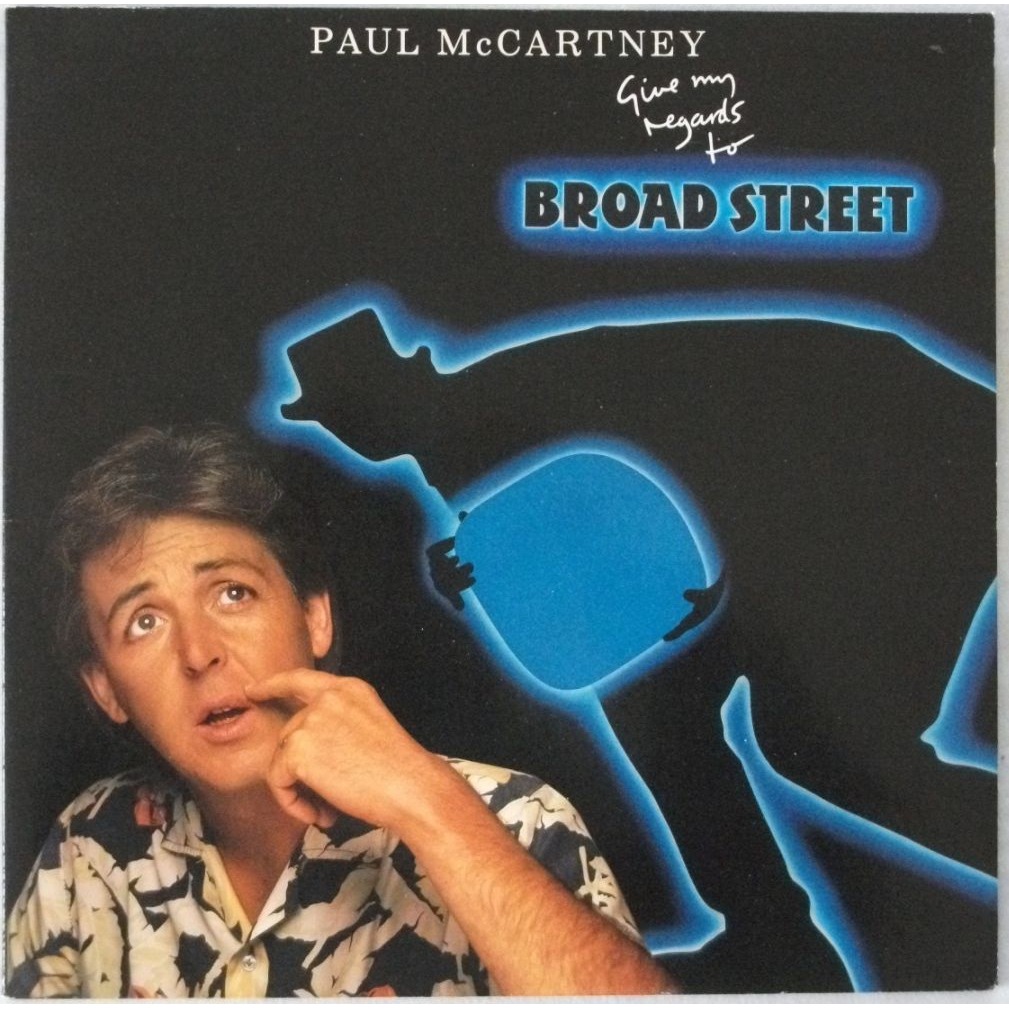

McCartney was visiting Chicago to promote his new movie, “Give My Regards to Broad Street,” opening Friday. It is not, in my opinion, a very good movie. It contains a lot of wonderful music, and the soundtrack will be a treasure, but the movie’s story about Paul in search of some missing tapes is, to put it charitably, idiotic. Still, McCartney could do anything and I’d watch it. He could even do a music video with Michael Jackson and I’d watch it.

He came into the room. He was, undeniably, Paul McCartney, and there is that star aura about him, for anyone like me who saw “A Hard Day’s Night” when it first came out. We have the same birthday, June 18, and McCartney is the kind of star who makes you remember dumb fan things like that, long after you start picturing yourself as a hard-bitten reporter. Besides, as long as I’m the same age as Paul McCartney, I will never really be old.

A publicist led him to a chair. A publicist gave him a glass of water. A publicist started taking his picture. There were several publicists left over. I told him it was a little astonishing how many McCartney fans there were: I had been getting phone calls for days from people who wanted to come along on the interview.

“I understand that,” he said, “because I was a fan. When I was about 14 or something, I was one of the boys at the stage door at the Empire in Liverpool, waiting for the Crew Cuts to come out. Do you remember them? They covered a lot of hits. They had the hit on ‘Earth Angel’ in England. And they talked to me. They gave me an autograph. They weren’t afraid of me. The word was out that Frankie Laine was not so friendly. That meant a lot.”

And so you stay in touch with that 14-year-old when fans come up to you?

“Oh, yeah. It can be a real warm thing. They just want to say, ‘Hey, Paul! Hi, man! I like your music.’ This morning I was jogging along the lakefront and a few people recognized me and it was fine.”

And when you were 14, did you want to be like the Crew Cuts?

“I stood in front of the mirror and practiced my stance, my expressions, the exact curl of my lip. Sure.”

And then, just a few years later, suddenly you guys hit the big time.

“Suddenly over here. Not suddenly in England. The old vaudeville and music-hall performers would say we hadn’t really put in time learning the ropes, but actually we had: In Hamburg, at the Indra Club, we were literally paid on the basis of our ability to get people in off the streets. We had a lot of work together before we began to know who we were. That’s spelled I-n-d-r-a.”

At the moment McCartney spelled the name, I got a sudden glimpse into the exact nature of this interview: The questions were new for me, but not, of course, for Paul McCartney, who has been interviewed in one way or another every day of his life for the past 21 years. He was being very pleasant, offhand and modest, but there was just the slightest suggestion that he was on automatic pilot.

“I’m a ham,” he said. “I love to get up in front of people and perform. What we were doing in Hamburg, in some way I’m still doing.”

Is that why you made this movie?

“I wanted to be involved in the making of a movie. I remembered from the time of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ and ‘Help!’ what a pleasant experience it is. And there’s a funny thing. It’s a real luxury, having 10 people looking after you. It’s silly, I know, but I come from a big working-class family in Liverpool, and we had to look after ourselves, and if someone wants to come and brush my hair, I must admit I like it. And being fussed over for makeup and costumes, I like that, too. Also, I like creating an illusion. I think I could have been very happy as part of the Muppets team.”

Let’s talk about the movie, I said.

“Right. I wrote the screenplay, you know.”

I wanted to ask you about the Victorian fantasy sequence during “Eleanor Rigby,” I said.

“Right. Well, I didn’t know anything about writing a screenplay, of course, but I just thought I’d try, and I got my pads and pencils and worked on it at odd moments over a year’s time. Most of it was quite detailed. But when it came to ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ there’s that moment when we’re playing with the string quartet in Albert Hall, and what can happen, when you know a song very, very well, is that your mind can drift. You know, what to give the kids for Christmas, and so on, while you’re still singing. So I just sort of imagined a group of images, graveyards and carriages, and wrote them in during the instrumental section. I think it’s a good thing to leave it unexplained. Like Bergman’s dreams. You know, like you’re holding Daddy’s hand and then his wrist is a tree branch, or you’re flying high over the school…”

Do you have that flying dream? The one where you suddenly realize that all you have to do is flap your arms and you can fly? And you feel silly that you didn’t know that before?

“Oh, yes. Definitely. And Michael Jackson figures he can fly. He really does. Given the right conditions. Me, I dream that I can do it, but only about a foot above the ground. In the old days, I could fly over the school, but these days about a foot off the ground is more my speed.”

But the fantasy sequence during “Eleanor Rigby” has no particular significance to the song?

“It’s more free association. Eleanor Rigby is symbolic, really.”

I figured that, I said.

“Some guy in Liverpool makes a living selling Beatles tourist books, and he claims to have found her grave. But there are a lot of Eleanor Rigbys.”

Yes, I said.

“As to why she’s called Eleanor Rigby…”

Well, I said, it’s the most pleasing grouping of syllables for a name. Three syllables in the first name, two in the second. Eleanor Rigby, Christopher Robin, Robinson Crusoe.

“McCartney Paulis. Make a note.”

You’ve started to paint?

“Oils. When I turned 40, I decided it was time to give myself permission to do things. I now run a bit, I paint a bit. The thing I’m most proud of is a portrait of Linda that I did one night while she was watching telly. It was when I realized that skin is not all one color. I painted her black, pink, red, blue, working them into the flesh tones.”

Do you think you’ll have a show?

“Perhaps, but the purpose isn’t really to have a show. The purpose is to do it for myself. Like writing. I’ll never be a great writer, so for a long time I was so intimidated that I would always get stuck at the first paragraph. Then, after my pot bust in Japan, I thought I had to write about it, and I did.”

That must have been a strange experience, I said, to go from being Paul McCartney to being just another prisoner in a Japanese jail.

“For nine days. Yes. I could have done without it. In the rich tapestry of life, that certainly provided a few threads. I wrote 20,000 words about it. Not for publication. Just for my kids to read someday.”

You’ve never made a secret of the fact that you smoke pot. But you’ve never gone over the edge into self-destruction like so many rock singers. When you were younger and could have had anything you wanted, whenever you wanted it, what enabled you to hold back?

“This may sound like a simple answer, but you see, it’s all in my roots. My family in Liverpool. My father was a cotton salesman and my mother was a midwife, and they raised me to do the best I could. Mom wanted me to be a doctor. He was a crossword man. Self-educated. He was the man who taught me to spell ‘phlegm,’ which I always knew would come in handy one day in an interview in Chicago. He was a lovely man. And the thing I always heard from him was ‘moderation.’

“I tried the teenage craziness of drinking pints and getting crazy. But with my upbringing, I never went over the edge. I’ve been near to it. When I first met Linda, there were nights when I had trouble getting my head off the pillow. I’d go out every night to the clubs and come home at 4 a.m., and finally she said, ‘Look here, buddy, you’re not in very good shape.’ A lot of people I knew were getting into trouble. In those days things were always around, but I never, for example, got addicted to heroin.”

Did you ever try it?

“No. But I was on a sort of unhealthy wavelength, and Linda did a lot of good for me at the right time.”

What about the days when the Beatles went to India to study under the Maharishi? Does anything remain of that spiritual period?

“When I have a headache, I’ll meditate to make it go away. Otherwise, I’m not wildly religious. I believe in God. I believe the Maharishi was a good man. They said he was taking in a lot of money, driving a big Merc, and all that, but he never wore anything but cheesecloth, and how much can you spend on cheesecloth? What I believe in mostly is the power of nature.”

One of McCartney’s publicists was hovering nearby, inhaling in a significant way, as if preparing to say that the allotted time for the interview was now over. As I was leaving the room, McCartney said, “Happy birthday. Next June 18th.”

Right, I said.

“You’d be surprised,” he said, “how many people I meet who have the same birthday that I do.”

I hardly ever meet anyone who does, I said.