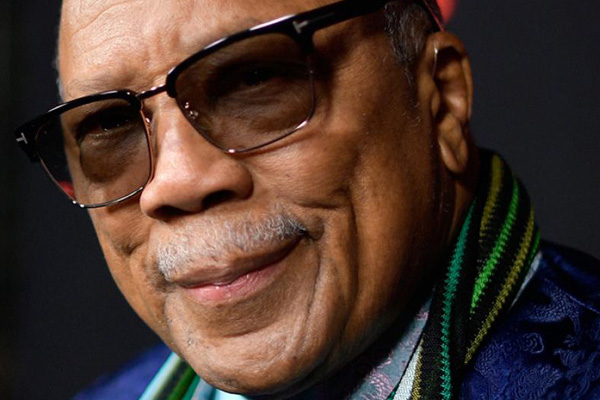

In the new documentary “Quincy,” the acclaimed producer/composer/artist Quincy Jones narrates his own life story, from his troubled childhood in Chicago, to his achievement in just about every musical field, to his tumultuous personal life. Directed by Rashida Jones and Alan Hicks, “Quincy” strives to craft a legacy narrative of Jones, one that covers the breadth of his accomplishments and places him as a pivotal figure in the history of 20th century music. The film flashes back between the past and the present, showcasing Jones’ many accomplishments and documenting his contemporary efforts, which includes producing the opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

We sat down with Quincy Jones and co-director Alan Hicks at the Toronto International Film Festival to discuss “Quincy,” music, life, and everything in between. For Quincy Jones, questions are merely a catalyst for free association, providing a certain musicality to his interviews. If you follow the thread, he’ll lead you to wonderful, unexpected places.

When did this documentary come to fruition? When did you [and Rashida] decide to create this tribute to Quincy’s life and legacy?

ALAN HICKS: Our journey with Quincy, he was involved with “Keep on Keepin’ On,” which is my first film. We got to know each other through that, and once that had finished, I met his daughter Rashida and we’ve become good friends. She had already started on this documentary kind of by filming him piece by piece, and she came up and asked me if I would co-direct the film with her. We said yes and all of sudden we started following Quincy, Rashida and I and two camera guys (a guy called Adam Hart and another bloke named Rory Anderson), and we followed him for three years filming. We filmed 800 hours worth of vérité footage, which is a lot. [Laughs.] Then we also collected 2,000 hours of archival footage. That’s how it kinda came about, but the seed of the idea for the “Quincy” film [came from a] conversation between Rashida and Jane Rosenthal. This is before I came into the fold…

QUINCY JONES: Into the fold?

AH: [Laughs] Yeah! That Rashida should do a film about her dad. So, that’s what ignited it and then we put together the same team as “Keep on Keepin’ On,”: Paula DuPré Presman, the producer from “The Cove,” and another film called “Chasing Ice,” and a lot of the “Harry Potter” films, and then the same film crew, and Jane Rosenthal, obviously, and me and Rashida.

I’m curious when the structure of the film came into place—the flashback structure, specifically. Was that from the beginning or was that developed over the course of the film?

AH: Rashida and I had talked about the structure when we were just coming up with ideas for the film, that we’d love for it to be a dialogue between the past and the present. This is before you see any film, no footage had been shot or anything, this was just a seed of an idea, and also within that we weren’t going to do any talking heads, no interview at all. Just use sound bites from Quincy from the different periods of his life so it could represent the era.

My next question’s for you, sir. This film crafts a narrative of your life and I’m curious how important is legacy to you?

QJ: It’s important to anybody. It’s proof that you’re on this planet, or doin’ whatever you’re doin’. [Points to Alan Hicks] They’re the best. They are! You saw “Keeping on Keepin’ On?” They don’t play. That was his first film.

In the film, you keep returning to your “humble” origins in Chicago and how you escaped the—

QJ: Humble?!

[Laughs.] I meant that tongue-in-cheek.

QJ: ‘40s. Depression. You kidding? Chicago is rough enough when it’s fine. Please, man. Imagine the ‘30s.

Of course. At what point in your life did you feel like you needed to confront the past as opposed to escaping it?

QJ: I confronted it all my life. Couldn’t help it. Were you close to your mother?

I am.

QJ: Well, I had no mother. They took her away in a straitjacket when I was seven years old. Dementia praecox. That’s not easy for my brother and I. He couldn’t handle it, he died in 1998, because the next one he married was like the lady in “Precious.” She was not a nice lady. Anyway, we got through it.

What does celebrity mean to you?

QJ: Not much.

You surround yourself with all these luminaries, I’m just curious if …

QJ: I’ve been around it all my life, you know. Billie Holiday at 14, Billy Eckstine, all of them.

My next question involves the concept of being a survivor.

QJ: Oh, I’ve definitely been a survivor.

Something that the film neatly conceptualizes is the idea that you’ve had all these close calls, and you’re sort of grateful …

QJ: To be vertical, absolutely. I’ll take it anytime.

Do you feel like you’re living on borrowed time?

QJ: No, not at all. Just startin’, man. They promised me 30 more years. I’ve been on the board at MIT with Marvin Minsky and [all these guys]. They don’t play. Nano technology is gonna turn this world upside down. Marvin Minsky created that. He was also the co-founder of artificial intelligence with Patrick Swyggerty [INTERVIEWER NOTE: He might mean Patrick Winston. I can’t find anybody by the name of Patrick Swyggerty, spelled various ways.] They don’t play.

Is the documentary a new chapter in your life?

QJ: New chapter? It’s on the old chapter! It’s based on the old chapter.

My next question is for you [Alan Hicks]. What did you learn about Quincy that you didn’t know beforehand?

AH: Oh my God. Growing up, I started playing music and jazz when I was about 13 years old, and one of the first records that I got was a Quincy Jones record. I’d been so familiar with Quincy—well, a little bit familiar as a child growing up, then when I moved from Australia to New York, my dad, when I was at the airport, he bought me a book and said, “Here’s a book for your flight,” and it was the Quincy Jones autobiography.

QJ: Really?

AH: Yeah, man. In that book is a chapter written by Clark Terry as well.

QJ: That’s right.

AH: Yeah, the Rugrat. So you fast-forward a bunch of years and, thankfully, I ran into Clark Terry and was able to make his film. For me it’s been a total education. When you’re making a documentary like this, you spend every day learning something about the character. For me, it wasn’t like—I dunno, if I had to do a film about another figure that wasn’t a musician that I didn’t really admire, it might’ve been boring. But for Quincy, every time I found a new song, or a new record, or found out he did this or did that, it was just invigorating, every step of the way.

But the best thing was that we got to spend so much time with Quincy. We traveled with him for years.

QJ: All over the world.

AH: All over the world. I think it’s about 25 countries that we were lucky enough to go with him to. I dunno, it’s just been a pure pleasure and honor to be around such a great.

QJ: Right back at you.

AH: Thanks, Q.

[To Quincy] What’s your favorite place to visit in the world to visit?

QJ: You mean between Stockholm and Cape Town and Cairo and Rio and St. Paolo and Beijing and Tokyo? C’mon. They’re all great, especially if you know 30 or 40 words in the language, it takes you through the food and the music. Rio, come on. Angola controls all of the culture of Rio, it’s Portuguese language, but all African influences, polyrhythms and all that stuff. It’s why Bossanova is so good. They don’t play, man. And Cuba, too. And Puerto Rico.

I’ve always wanted to go to Puerto Rico.

QJ: Is your girlfriend Puerto Rican?

No, no. I’ve just always wanted to go.

QJ: We’re gonna get you in trouble, huh?

[Laughs.] I think the most interesting part of the documentary is your belief in decategorizing music and breaking down genre walls.

QJ: Well, I was trained for that with Ray Charles, because we used to play everything in Seattle when we were 13 or 14. We played white tennis clubs, played pop music back then in the ‘40s. Then we go to the black clubs, the Washington Social and Education Club, which was a bottle club. Reverend Silas Groves was in charge of it. We played for strippers, and rhythm and blues, everything you can imagine. I mean, Debussy, Sousa, bar mitzvahs, bat mitzvahs, we played for everything, man. I came up with guys, Bumps Blackwell and Ray Charles, that said you have to respect each genre of music, you know? It’s either good or it’s bad, but if it’s good music, you respect each genre. We’ve been stuck with—well, blessed, I should say—with 12 notes for the last 700 years. That’s heavy. That’s all we have is 12 notes. The first guys—Brahms, Bach, and Beethoven—took all the good stuff, you know? Through rhythm and harmony, we had to find a way to make those melodies ours. It feels like you belong to it, and that’s not so easy.

What do you believe is your most overlooked accomplishment? What is something that people don’t talk about enough that they should?

QJ: I don’t know. I just keep on going. Really, man. I got promoted to be the first black vice president of Mercury Records, that’s the first time that happened, and I was happy about that, but I really wanted to write for movies. They offered me a million dollar contract for 20 years. I said, “No, man. I’m gone.” And I quit, and I went to Los Angeles to start writing for movies, because that’s what I really wanted to do. I have never, ever done music for money or fame. I mean, never, and I never will.

What was your favorite movie growing up? The one that got you into wanting to write for film?

QJ: I used to go to down the Skid Row when I was, like, 14 and 15 in Seattle. 11 cents a movie. After about a year or so, I could tell the influences that Alfred Newman had at 20th Century Fox. Every composer there used him as a guideline. The same with Victor Young at Paramount and Stanley Wilson at RKO. I could tell, I could feel that. I had a natural passion for film scoring. I don’t know why. I was into art before I was into music, and I have synesthesia. You know what that is?

Yes I do.

QJ: Okay, I have synesthesia, too. I see it before I hear it. It’s off the wall, but I like it. It worked good for me.

Do you see music in colors?

QJ: Yep. Primary and secondary colors. Watercolors. Black-and-white sketches. And then oil, because oil is final. But the psychology of it is a good leader, too.

Do you think you invented the Wall of Sound before Phil Spector did?

QJ: Oh, man, gimme a break. It’s about orchestration, man. I went to Nadia Boulanger to learn about orchestration. She taught Leonard Bernstein, Aaron Copland, and Stravinsky. I saw Stravinsky every day. And [Maurice] Ravel’s like my favorite orchestrator on the planet. He was influenced by [Nikolai] Rimsky-Korsakov. He was a virtuoso orchestrator. Boy, the French people really know how to do it. The woodwinds and the strings. That’s why I went over to Paris. Sat with musical director of Barclay Records. Boy, that was the best experience in the world.

[To Alan Hicks] When did you come to an ending with this documentary? What did you see was the culmination?

AH: Well, Rashida and I … you’re always looking for an ending. Even when you’re filming, you’re trying to figure out what’s the through line. Something that really popped out was the African-American museum and because we figured that out while we were filming, we were able to focus in hard on that. It’s really once you get into the editing that Rashida and I could really shape it and figure it out. The funny thing about documentaries is that they’re done when they’re done. They organically come about. For example, a single scene we might have been slightly editing that for a year-and-a-half. The editing process went over almost the course of two years. So, you are continually revising, but with a story like this, it just happened. The ending presented itself. That’s what it was. It doesn’t work like that.

QJ: There really is no ending.

AH: Yeah.

QJ: Not yet, I hope.

AH: That was also our thing with the ending, to give that feeling that there isn’t an end. Quincy is going to keep flying forward.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. “Quincy” will be available to stream on Netflix on Friday, September 21.