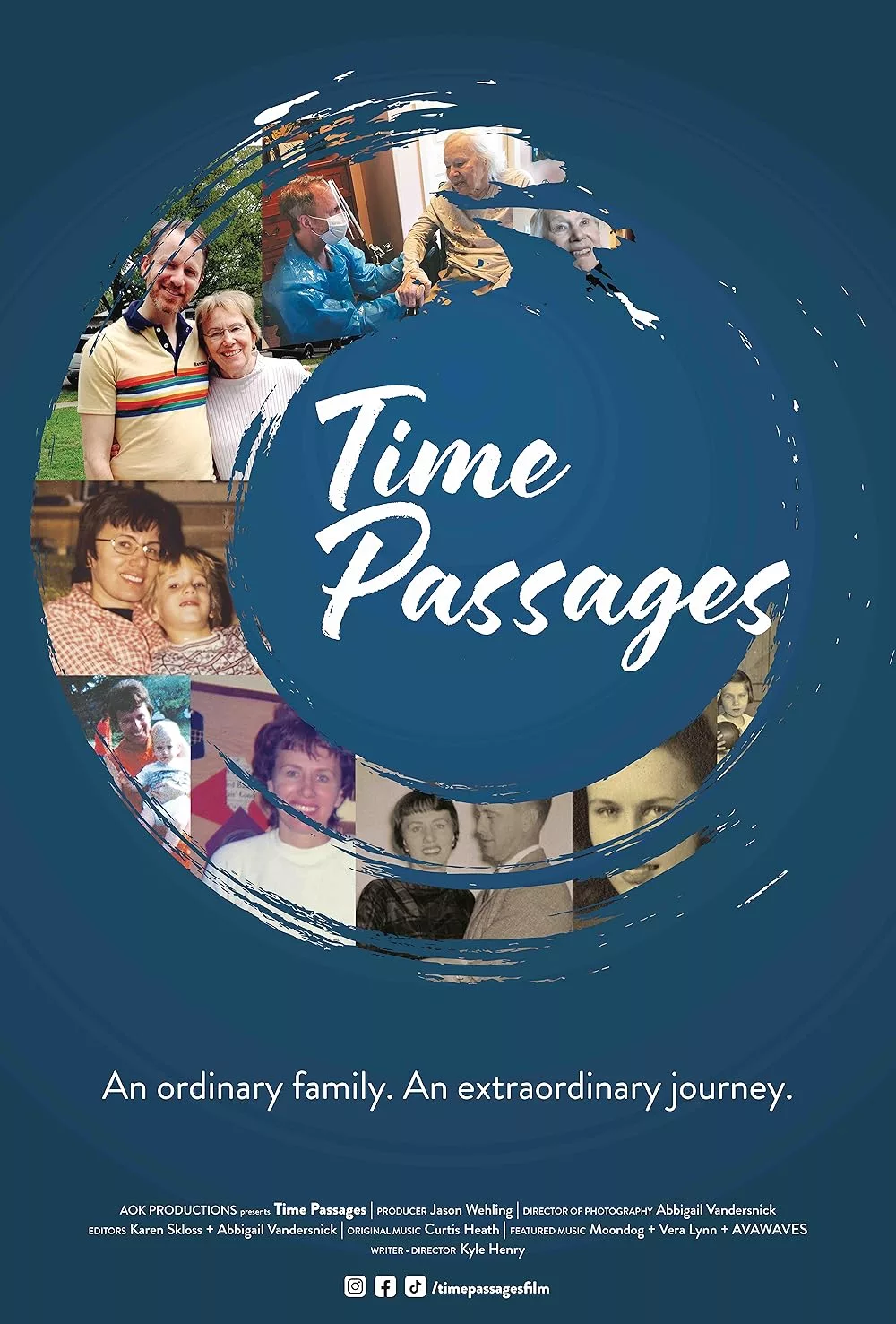

Kyle Henry’s nonfiction film “Time Passages” is a quasi-experimental work in which the filmmaker grapples with his mother’s decline from dementia, reconstructing his own life and the formation of his personality as he tells the story. I haven’t seen anything quite like it before. That alone makes it worth seeing, as long as you accept the proposition that a movie like this is unique, in some ways beyond genre labels, and feeling its way towards the right flow and shape as it goes.

At its best, “Time Passages” becomes one of those movies that makes a reviewer wish the star rating could be suspended for certain titles. You could reasonably argue that parts of it don’t “work” in any conventional sense, and it sometimes lacks focus. Despite a deep archive of family records, including reel-to-reel audio recordings and home movies shot on film, it sometimes seems there isn’t enough firsthand interactive material documenting the filmmaker’s direct interactions with his mother, Elaine, to keep the focus on her. And so Henry’s own autobiography (including ruminations on his emotionally and politically conservative upbringing in the American South, his status as the youngest of five siblings, and his coming out as a gay man) takes center stage a lot. That is not in itself a bad strategy, just one that substitutes a movie you’ve likely seen before for one you likely haven’t. But the movie you haven’t seen is amazing.

Henry, a film professor by day, has taken the struggle to sift and organize his raw material and structure it into a coherent narrative and turned it into part of the experience of watching the movie. He has a performer’s instinct and often presents material as if we were watching a stage play in a “black box” theater, where the actors have minimal props and no backdrops. The first sequence in the movie shows Henry holding canvases of varying sizes against himself as he projects home movie footage onto them, visualizing the idea that his mother’s memories have become his own by virtue of having been recorded, preserved, and played. There’s also the simpler idea that our parents’ lives are encoded within us.

“Time Passages” is filled with many such scenes. When it’s in this investigative/archival mode, it’s about as personal and uncategorizable as movies get. The struggle to figure out whether a piece of data “fits” into the story and might connect emotionally with the viewer, or is interesting only to Henry for his own private or familial reasons, shows in moments where we hear Elaine speaking on one of the audio recordings, but we are looking at a series of disconnected family photos or mementos. It’s as if a historian is going through an archive for the first time and doesn’t always know what they’ve just pulled out of a box.

There are long sections where the movie seems to have no idea how to solve a new problem, tell a story for which inadequate (or zero) visual or audio material exists, or connect the stories of the mother, the father, the son, and other important figures. There’s also an ongoing sub-thread about the Kodak corporation that never convincingly merges with everything else—but, paradoxically, it does feel relevant to the project, at least in terms of contrasting the idealized imagery presented in Kodak Motion Picture Film ads and the messy realities of real people’s lives, as well as the fact that artistic formats, corporations, and institutions decline and die, too.

The editing, by Karen Skloss and Abbigail Vandersnick (who also shot the movie), is functional and purposeful but also expressive, somehow communicating the feeling of chaos being collected and dumped into a container marked “order” but spilling over the top anyway. Only those suffering from dementia can know what the experience is like. Still, I would imagine that this movie’s more lyrical and intuitive moments approximate the struggles and burdens of a person in that state. It rings true. A word springs to mind: inchoate, which means a thing “only partly in existence or operation: incipient; especially: imperfectly formed or formulated.” This is an inchoate movie, inevitably so, and heroic for embracing a challenge that it might not be possible to master.