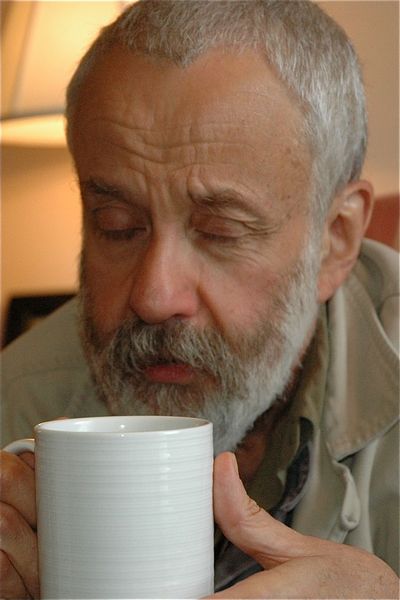

For years he was the consummate outsider in the world of British film. Now he’s hailed as one of the UK’s greatest directors. He is still an outsider, but things are looking better. “I think I’ve probably progressed,” Mike Leigh told me, “from being the outsider’s outsider to perhaps, in fact, being the insider’s outsider.”

This was in September at the Toronto Film Festival, where Leigh’s wonderful new film “Happy-Go-Lucky” was playing. It plays Friday in the Chicago Film Festival, where his entire career got its start in 1971, and he will be awarded CIFF’s Lifetime Achievement Award. It opens here Oct. 24.

Leigh spent 17 years between his great first theatrical film, “Bleak Moments,” and his second, “High Hopes” (1988). Since then, he’s made eight more films, all of them vibrating with his peculiarly engaging characters and liberated plots. He’s probably best known for “Secrets and Lies,” “Topsy-Turvy” and “Vera Drake.” During the 17-year drought, he worked steadily writing and directing theater and making films for the BBC. But the working method he insists on made it impossible to find financial backing.

Although there is an impression in some circles that Leigh films are improvised, they are actually tightly scripted. It’s how they get that way that scares backers. He starts with a notion for a story and some actors he admires. Together, they define characters and “devise” improvised situations for them, and a screenplay emerges. Leigh refuses to show backers a script in advance, will accept no consultation on his choice of actors, and demands final cut. Still, I can’t understand why investors are shy of him: What do they really know about movies? They often end up backing trash and losing money. What other director do you know who has never made a bad film, has been nominated for three Oscars, and whose films have oodles more nominations?

Sally Hawkins deserves a nomination for her virtuoso work in “Happy-Go-Lucky,” where she plays an unflaggingly cheerful school teacher of around 30 whose life takes a bizarre turn when she signs up with the wrong driving instructor. The instructor is played by the British comedian Eddie Marsan, in anything but a funny role.

“Initially our improvisations involved having the actual car,” he told me, “and going around the streets and actually improvising the situation from the word go, the actors not having met each other in character, and me lying in the back seat with the hilarity of what was going on, and trying to control myself, and then the dreadful London street which the rear suspension of a Ford Focus is hardly the answer for. We worked very thoroughly to get those complex scenes right. And these guys would leave no stone unturned. It’s about the truth of the moment. It’s ‘moments’ again.”

So okay, you’ve sunk your money into the production and Leigh is driving around lying on the back seat. What did he start with?

“What I did,” he said, “is collaborate with actors to create characters, and somehow two things came together. One was that, having worked with Sally Hawkins in the last two films and gotten to know her, I felt now was the time to make a film that would put her at the center and to create something extraordinary. The other was, I wanted to make a film that I could call an anti-miserableist film. A celebratory film, because there is a massive amount for us to be gloomy about in 2008. There are people out there who get on with it, not least amongst whom are teachers, who are by definition cherishing, nurturing the future. I knew that Sally and I could create as a character who was explosive and energetic and positive.”

And they did. It’s impossible for you not to smile along with her, unless you hate her, of course.

“It’s interesting that there’s a reaction,” he said, “a minority one, but nevertheless a constituency that reacts to ‘Happy-Go-Lucky’ by very unequivocally, saying, ‘I can’t stand this woman. By the end I wanted to kill her.’ It’s quite a number of British critics and there have been some of those responses here at Toronto. I just don’t get it. It comes from a way of looking at movies which is more about looking in terms of movie language than about looking in terms of people and the world out there. It’s insular and cynical.”

Every Leigh film takes a detour into an unexpected direction. In this one, the heroine has a conversation with a shabby homeless man who seems to have nothing to do with anything but turns out to be emotionally invaluable to the scenes that follow.

“She has great empathy, she’s open, she listens,” he said. “I mean, she’s walking about and she hears this strange chant and comes across this tramp, and she’s open, she’s non-judgmental.”

I loved that scene, I said. She listens to him, asks him if he’s hungry. She isn’t afraid; she’s worried about him. I think he’s aware of that, and it soothes him. It is possible nobody has spoken to him in days or weeks.

“Absolutely,” he said. “Again there’s a constituency of people who said, ‘I just don’t understand that scene. It’s out of style with the rest of the film. It’s a red herring.’ I’ve been encouraged to cut it at certain stages. It beggars belief, but there it is. There are important things about this scene. You see her walking about in a kind of park. She’s in her own space, in a quiet place . She comes across this guy, ask him how-do-you-do, goes back to her apartment, and never says where she’s been. It isn’t a kind of a plot thing, you know. It’s just that some things are private, some things you kind of just hang on to.”

The thing about Mike Leigh is that, using his method, he figures out where the private things are, and goes there.