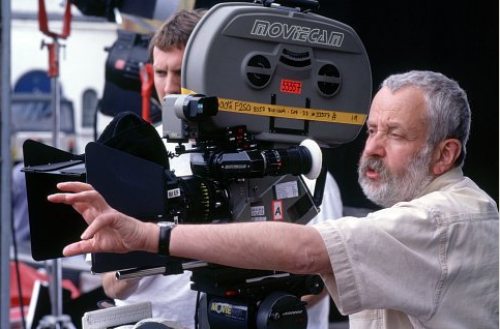

Interview on Sept. 9, 2008 at the Toronto Film Festival.

Roger Ebert: I find myself so drawn inside your work. Nobody else does what you do, and it was all there right from the start.

Mike Leigh: Well, I have to say, if anybody knows that, you do, and it’s always special to catch up with you because your review of [Leigh’s first film] “Bleak Moments” is one of the seminal experiences in my life. The original the connection, the continuity, between “Bleak Moments” and “Happy-Go-Lucky,” I know what you mean. It makes absolute sense.

RE: I’ve seen Sally Hawkins, but I haven’t seen her play characters anything like this. What made you believe she was the right choice for this extremely difficult role?

ML: What I do is collaborate with an actor to create a character and somehow two things came together. One was having worked with her in the last two films and having gotten to know her, I felt now was the time to make a film that would put her at the center and to create something which would be extraordinary. At the same time, I wanted to make a film that in some way, I could call an anti-miserableist film. A celebratory film, in some way, because there is a massive amount for us to be gloomy about in 2008.

There are people out there who get on with it not least amongst whom are teachers, who are by definition cherishing, nurturing the future. I knew that Sally and I could create as a character who was explosive and energetic and positive . And also, every time I make a film, I try within my limited genre, I try to do something different. Every time I invite you around to dinner I don’t like to serve up the same dish. And I felt, having done “Vera Drake” and “All or Nothing,” I thought actually now is the time to do a film which is positive and upbeat and kind of a celebration of life. And so the collusion of those two things, there’s that, and the notion putting Sally at the center of things and tapping into her own unquestionable energy and humor and spirit, I just thought it was the right thing to do.

RE: Her character has to build toward that powerful confrontation with Eddie Marsan, but you keep that progress mostly under the surface, I don’t know if we see it coming, but it seems right when it arrives.

ML: Of course when it arrives we know it’s inevitable. A lot of people now keep saying they I thought something terrible was gonna to happen and they were going to crash in the worst way. To some degree that’s all about the expectations that are hardwired into people from watching Hollywood movies. The important thing is, that she knows how to deal with it The question is, why the hell does she go on having driving lessons? But there’s a point in this game when she’s told, “You can always go to another instructor.” She says, “Well, we’ll see how it goes.” Her earthen spiritedness and generosity gives him the benefit of the doubt. And her own sense of humor gets the better of her, because like all people with a highly developed sense of humor, amongst who we can include ourselves, when you meet somebody who is totally devoid of a sense of humor it brings out the worst of you. She knows that. So when she’s kind of cheeky, she’s just really trying to be nice. She just can’t help it. Obviously it takes a serious turn when he’s obviously stalking her outside her flat. The important thing is that finally she knows how to deal with it, because we’ve already seen that she knows how to deal with kids and he’s a kid, basically. He’s a very immature man, and she can see what’s going on.

RE: Eddie Marsan has been around for a long time, and is well known as a comedian. Without having seeing everything he’s done, it looks to me that in “Vera Drake,” you were the first, certainly one of the first, to use him in a serious role.

ML: Yes. I don’t know whether _____ entirely true of actors. I mean, you have minor serious role and even in “Gangs of New York,” and “21 Grams,”….that was after the _____. Well, anyway, what’s the question?

RE: You saw him as a serious and a good actor.

ML: He’s a very great actor, actually. He is, incidentally, as a person, an extremely funny man, as Sally Hawkins is. But, boy, can he bore down find to the core truth of a character. A real find, as far as I’m concerned. He does a remarkable thing, does he not, in “Vera Drake” [as the daughter’s shy suitor]. He’s a classic case of what I do, which is where I get an actor and I have no idea of what we’re gonna do except that I know that it’s going to be a feast of possibilities and we’re gonna find something extraordinary.

For me, that’s the turn-on of the whole business of making these films; going on this journey, discovering for myself what it is that I’m after, with all its concomitant surprises. Sally and all these people with no exception really are hardworking actors, uncompromising, who really won’t let it go. There are the car driving lesson scenes. Apart from initially doing improvisations which involved having the actual car and going around the streets and actually improvising the situation from the word go, not having met each other in character, and me lying in the back seat with the hilarity of what was going on, and trying to control myself. and then the dreadful London street which the rear suspension of a Ford Focus is hardly the answer for. And then converting all that into scenes, we took a lot of days during the shoot, time outs, to work very thoroughly to get those complex scenes right. And these guys would leave no stone unturned. And it’s very rich and stimulating but at the same time, they hung on to these characters . It’s about the truth of the moment. It’s “moments” again.

RE: When you began in filmmaking, you were the classic outsider. Now you are considered one of the greatest British directors, and you have the O.B.E. Yet at the beginning, your films had trouble even being shown in the U.K. Is there a lesson to be learned in all of this?

ML: It’s just not a question with an answer, with all due respect. I don’t know whether the O.B.E is very relevant. I am obliged to tell you, unless it’s something you already know, and Ken Loach would be here telling you the same thing, he probably has, but it remains quite tough getting our films on British screens. With “Happy-Go-Lucky” it’s not quite as bad as it has been. It’s not the way the market is dominated by the Hollywood films; we are swamped with so many films. That’s an international problem. There are just so many movies kicking around that, other than being out-blockbusted, it’s very hard to hang on in there with more than a limited amount of time, which is a shame. The films go to DVD much quicker and sooner than they used to do.

But I would have to say in the terms of your question that I think I’ve probably progressed from being the outsider’s outsider to perhaps, in fact, the insider’s outsider. I’m still really an outsider. And I think that’s quite a healthy thing to be. I haven’t especially sought it although I make choices that probably, consciously or otherwise, guarantee that I remain an outsider. I will only do projects where there’s no interference in casting and all that business. There are prices I pay for that. I still can’t get budgets beyond a certain sphere; therefore we make films that look comparatively good working with such skilled people. I’m still extraordinarily cheap, and the truth is that I would dearly love to paint on a bigger canvas. The only time I’ve really done that was “Topsy-Turvy.” “Vera Drake” you could argue is that to some degree. Even “Topsy-Turvy” which was made 10 years was made for only 10 million pounds which was very little.

There are some specific projects. I would like desperately to make a film about J. M. W. Turner, the great painter, who is a fascinating character. It would lend itself to a great cinematic revelation. With “Topsy-Turvy,“ we actually started out with a bigger budget, but while we were actually doing it the budget shrank particularly because of the Southeast Asia crisis. the area pulled out, to the tune of a million and three-quarters pounds while we were already doing the picture. So, we made compromises. There are virtually no exteriors in “Topsy-Turvy,” and the ones you see–there are three, I think–were constructed in a very cheap way at the back of the building somewhere. So it’s a very interior film.

You don’t make a film about the great Turner who struck himself to a mast of the ship to paint his dog . He went to Venice and everywhere else in the Mediterranean and painted seascapes. You don’t do that by cutting out all the exteriors. You can’t for a second leave anything out in England. So it would be vastly more expensive but I have floated the idea in various places, but actually, nobody, but nobody, is interested, because I insist on my scripts, no interference, etc., etc., which is absolutely non-negotiable. It stitches me up and leaves me in this curious territory where I can have absolute freedom but only with limited resources. And, in a way, you could argue and perhaps you, Roger Ebert, would argue that, well, actually, it’s not a bad thing because that made me have a bit of discipline to make the films that I made. And I think that’s true, but however, I’m 65, and I will go on making films as long as I can physically….how old are you?

RE: Sixty-six.

ML: Sixty-six. So, we know that we keep it going, I should keep going, but time will run out and it’s good to get on with these things if you can.

RE: Our London friend, Gillian Catto, spent years trying to put together a Turner film starring her next door neighbor, Peter O’Toole. He would have played Turner’s father and Bob Hoskins would have been Turner.

ML: Oh, really? Well, I’m sorry that she couldn’t do that but I’m delighted that it didn’t happen because I would hate to not have it to aim for. It’s interesting that somebody’s already had the idea, really.

RE: In the years of exile from mainstream film, you worked constantly in the theatre and directed many of your scripts for television. Did that period contribute to your emergence as a film director, or was it simply a delay?

ML: No, it wasn’t a delay. I mean, at the time, I, like others, spent a lot of time sitting around lamenting the fact that we weren’t making feature films. Certainly, if you’d told me in 1971 when we made “Bleak Moments,” the next feature film will be in 17 years time, I think I would have been extremely distressed. I’d probably have jumped over Waterloo Bridge. But, of course, the truth is that it would have been impossible, during that period, to have made feature films.

First of all, it was impossible to make feature films; indigenous, independent, serious, feature films in the UK anyway. It didn’t happen for anybody. But even if there’d been a way of doing it, I don’t think I would have got into trouble with it because I don’t think the system would have cared for the way I did things. But, of course, worked on and off, freelance, partly doing theatre and partly doing the television films, as you say, over 12 years. And the thing about the BBC, because that’s where it all was, was it was then, as you know, a totally liberal organization. I would go in and they would say, “Well, those are the dates, that’s the budget, five weeks, six weeks, shooting, whatever– go away and make the film.” And that was the end of that.

So by the time Channel 4 started in the early to mid-80’s, which changed the landscape because the whole notion of theatrical production financed by television could happen, I’d got a portfolio and established that this kind of work was viable. But apart from that, apart from the economics and politics, I had spent all that time developing and growing and learning the craft and making these films without interference and, getting better at it, really. And I’m making mistakes and some of them are not as good as others and by the time you get to the likes of [the BBC film] “Grown Ups,” that is well-crafted. So there is no doubt that the reality is just what you say, which is that, absolutely, had I gone straight into the one or two feature films that were out there, there would have been many less films that would have been made. I can’t really see how any would have been made at all but if I had, it would have been much less rich experience and certainly, the sheer fact of doing, I think, nine films or something like over a decade or so, I could do what artists should do, you know, is to be out there with my sketchbook. My camera was actually doing it, you know, and not just sitting around in filmmakers’ offices, just dreaming and procrastinating and becoming embittered and frustrated. I mean, I found things like “Abigail’s Party,” which was much advanced stuff.

RE: I was so happy to see that DVD collection.

ML: Have you seen the actual DVD collection? Have you got it, in fact, the boxed set? The British boxed set? Yes, not the American pirated one, the British one.

RE: I have an all-zone player.

ML: Oh, good. You have the British one. There’s another one coming out…

C: Is that pirated?

ML: Oh, there’s always been a pirated one in the States. We let them do it years ago on the basis that at least people would be able to see the damn films. But that’s been superseded now by our popular new British collection. And there’s another one coming out next year of all the television films which have been re-mastered and I’ve done direct commentaries and everything so you’ll actually have the complete works. And I’m very pleased too because, you know, you make these films and then they sink into obscurity and then all that effort goes to waste

RE: Changing subjects slightly, it seems to me that Timothy Spall is the ideal actor for you, for creating a man who to one degree or another is laughing on the outside, crying on the inside. [Leigh used Spall in “Life Is Sweet” (1991), “Secrets and Lies” (1996), “Topsy-Turvy” (1999) and “All or Nothing” (2002).]

ML: Absolutely. He’s very much an actor with an incredible emotional depth and great compassion for the pain with a massive sense of humor, you know, absolutely. He’s a great actor. And I haven’t finished with him yet.

RE: Some of your critics say you make your characters into targets of condescension. I have never, ever, felt that. I believe that you accept their shortcomings and complexities and you love them.

ML: Well, you know that and I know that and we’re in total agreement about that and I think that those critics to whom you refer, tell more about themselves than about the work I do. In a way, it’s interesting that there’s a reaction, albeit a minority one, but it is nevertheless a constituency that is around that reacts to “Happy-Go-Lucky” by very unequivocally, saying, “I can’t stand this woman. By the end I wanted to kill her.” I don’t know if you’ve seen any of those but there are some. It’s quite a number of British critics and there have been some responses here at Toronto, from some of the press people. I just don’t get it. It really comes from cynicism. And it comes from a way of looking at movies which is more about looking in terms of movie language than it is about looking at films in terms of people and the world out there. It’s insular and cynical.

RE: Poppy [the Sally Hawkins character in “Happy-Go-Lucky” has great empathy. For example, with the little boy she’s teaching

ML: What is important and to me fascinating and significant about her is, she has great empathy, she’s open, she listens. I mean, she’s walking about later on in the film and she hears this strange chant and, she comes across this guy, this tramp, and she’s open, she’s non-judgmental.

RE: I loved the scene with the homeless man. She listens to him, asks him if he’s hungry. She is not afraid; she’s worried about him. I think he’s aware of that, and it soothes him. It is possible nobody has spoken to him in days or weeks.

ML: Absolutely. The interesting thing is that there is again a constituency of people who said, “I just don’t understand that scene. It’s out of style with the rest of the film. It’s a red herring.” Indeed, I’ve been encouraged to cut it at certain stages. I mean, it beggars belief, but there it is. There are important things about this scene. Prior to that, you see her walking about in a kind of park. She’s in her own space, you know, just in a quiet place . She comes across this guy, ask him how do you do, goes back to her apartment, and she never says where she’s been. It isn’t a kind of a plot thing, you know, what she’s trying to hide. It’s just that some things are private, some things you kind of just hang on to.

RE: I think that scene is instrumental.

ML: I feel that. Also, apart from anything else, the man is another remarkable actor, Stanley Townsend, he’s an Irish actor, he did a remarkable thing. Did I tell you where it was shot? That was shot in the guts of the old Battersea Power Station, if you know that building on the River Thames? It’s a strange building with four chimney stacks, on the South Bank and nobody knows what to do with it, but it’s a listed building, a great art deco building and it stands there and costs a fortune to maintain. On the whole, I don’t tell people where we shot it because I like that scene. I realized that if she just ran into him in the park in broad daylight, it wouldn’t have the same edge to it and the same focus and so I said to the production designer, it needs to be somewhere where we don’t actually know where we are, you know, so we shot it in there and you can’t tell where it is. I wanted somehow subliminally to have the audience to be pulled out of their comfort zone.