The first thing that happened to Stanley Kramer after he walked through the door of the Old Town Saloon was that a young lady said: “You Stanley Kramer? I hated your movie.”

“Caution, my dear,” Kramer said. “Don’t get irregular before your time.”

“What a fink-out,” the lady said. “What a phony plot. Not only would the girl marry Sidney Poitier, but anyone would marry Sidney Poitier. So what did you prove?”

Kramer put his hand on the young lady’s arm, looked deep and steadily into her eyes and pronounced: “To know you is to love you.”

“Yeah,” said the girl, “but I’m not Sidney Poitier.” Kramer wrinkled his brow. “If you were,” he said, “we would have had to make some big changes in the story.” “Funny, funny,” said the young lady. “Who writes your jokes? Raymond Massey?”

Kramer sat down in a front booth of the saloon and found an enormous photograph of Brendan Behan staring him in the face. “Whose idea was it to come here?” he asked. “What was wrong with the Pump Room? Wasn’t I wearing a tie, or something?”

“You’re in one of the most famous bars in Old Town,” someone said. “In the seat you’re sitting in now Mike Nichols and Elaine May once sat.”

“No, that’s probably not true,” someone else said. “This place wasn’t here when Nichols and May were here.”

“What did they do?” Kramer asked. “Sit on the ground?” He ordered a pitcher of half-and-half and asked what everybody else was having.

“This is all I need, the most famous saloon in Old Town,” he said. “I spend six days talking to students on the campus, and they give me the most famous saloon in Old Town.”

Where had he spoken?

“Oh, Stanford, Michigan, you name it. I had a rough time. It used to be a movie director could make a speech on the campus, and that was that. But the college kids have been poisoned by that Kael woman before I get there. Pauline Kael. The one who wrote 9,000 words about ‘Bonnie and Clyde‘ in The New Yorker when 90 would have been enough. She goes around giving speeches about all the phonies in Hollywood and then I arrive in town. A big, fat sitting duck.”

He sipped his half-and-half and found it good.

“You know what’s the matter with the approach these college kids take to movies?” he said. “They operate on the fetish system. If a director is an official hero, he can do no wrong. Hitchcock. Howard Hawks. The kids worship them; they memorize every foot of film. Hitchcock is very good, sure. But sometimes he makes clinkers, too. You’d think so. But not the college kids.”

He stretched out his feet and looked around. There was a coal stove in the room, and he said, “If there is no central heating in this building, then that coal stove is a nice touch. If there is central heating in this building, the coal stove is phony.” He was told the building had no central heating, and bestowed the coal stove a benevolent nod.

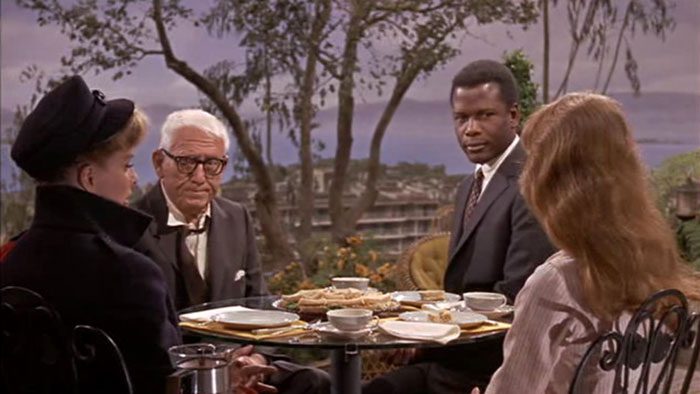

“Now you take this movie,” he said. He was talking about “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner,” his latest film, in which Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn play the liberal parents of Katharine Houghton, who marries Sidney Poitier.

“People attack the plot on the grounds that it’s too perfect,” Kramer said. “You know. Poitier is rich and famous and practically ready to win the Nobel Prize. And Tracy and Hepburn are progressive, enlightened, liberal parents with lots of cash. And Katherine Houghton is an ideal young woman.

“Hell, we deliberately made the situation perfect, and for only one reason, If you take away all the other motives for not getting married, then you leave only one question. Will Tracy forbid the marriage because Poitier’s a Negro? That is the only issue, and we

deliberately removed all other obstacles to focus on it.

“I look at it this way,” Kramer said. “This movie has a good, well-written story and great performances. People come out of the movie happy and satisfied. They wish the young couple well. Sometimes people even cry during Tracy’s last speech.”

He leaned forward. “Think about that,” he said. “Here you have an interracial marriage, and audiences are practically throwing rice. But then the critics come along and say I chickened out by making Poitier a perfect Negro. He should have been a mailman instead of a famous doctor, according to them. But they’re wrong. They’re dead wrong. Because if Poitier had been a mailman, the girl’s family would have disapproved of him because he was a mailman, not because he was a Negro. Don’t you see?”

Sure. But couldn’t you solve that by making the girl’s father a mailman, too? Then, if they were both mailmen…

“That would have been another movie,” Kramer said. “We made this one. For one thing, the roles we made were perfectly suited to Tracy and Hepburn, and a great many people are going to be pleased that those two got together for one more film before Tracy died. They had something on the screen no other couple ever matched.” He poured another glass of half-and-half. “Tracy was a hell of a guy,” he said, remembering. “When he was a young guy, he was a real roustabout. Used to throw chairs through windows about once a night. He really screwed up his liver and kidneys. But after he slowed down and started to take care of himself, they patched him up pretty well. I did his last four pictures, and he felt better when he made this one than on any of the others. And then, what killed him was the first heart trouble he ever had in his life. Ironic.”

Kramer stretched his legs again and looked around, contented. “Tracy would have felt at home in a bar like this, for example,” he said. “No fancy stuff.” he scrutinized the photograph of Brendan Behan again, and said, “You know I’ve been looking at that damn picture since I came in and I’ve finally got it figured out. When you look at his mouth, you can see what he was saying the instant they took the picture.”

“What?” said the young lady, materializing from somewhere.

“My dear,” said Kramer, “I would like to tell you, but I really cannot.”