“Some people in life know exactly what they want to achieve. This is a book for the rest of us.” With these opening lines, Victoria Labalme’s invaluable new book, Risk Forward, invites readers to embrace the very uncertainty they are so often told to fear. It subverts and transcends the didactic tropes of the self-improvement genre by illustrating how no one, not even the author, “has it all figured out,” a truth that can free us to explore untapped realms of potential. Like Alan Watts’ The Wisdom of Insecurity or David Lynch’s Catching the Big Fish, Labalme’s book is a singular achievement that prompts us to view the world and our place within it in a wholly new light. It is an insightful, witty and deeply moving mosaic that is guaranteed to enrich the lives of people across countless professions, which is precisely what Labalme has done for over two decades as an acclaimed keynote speaker, performing artist and performance coach.

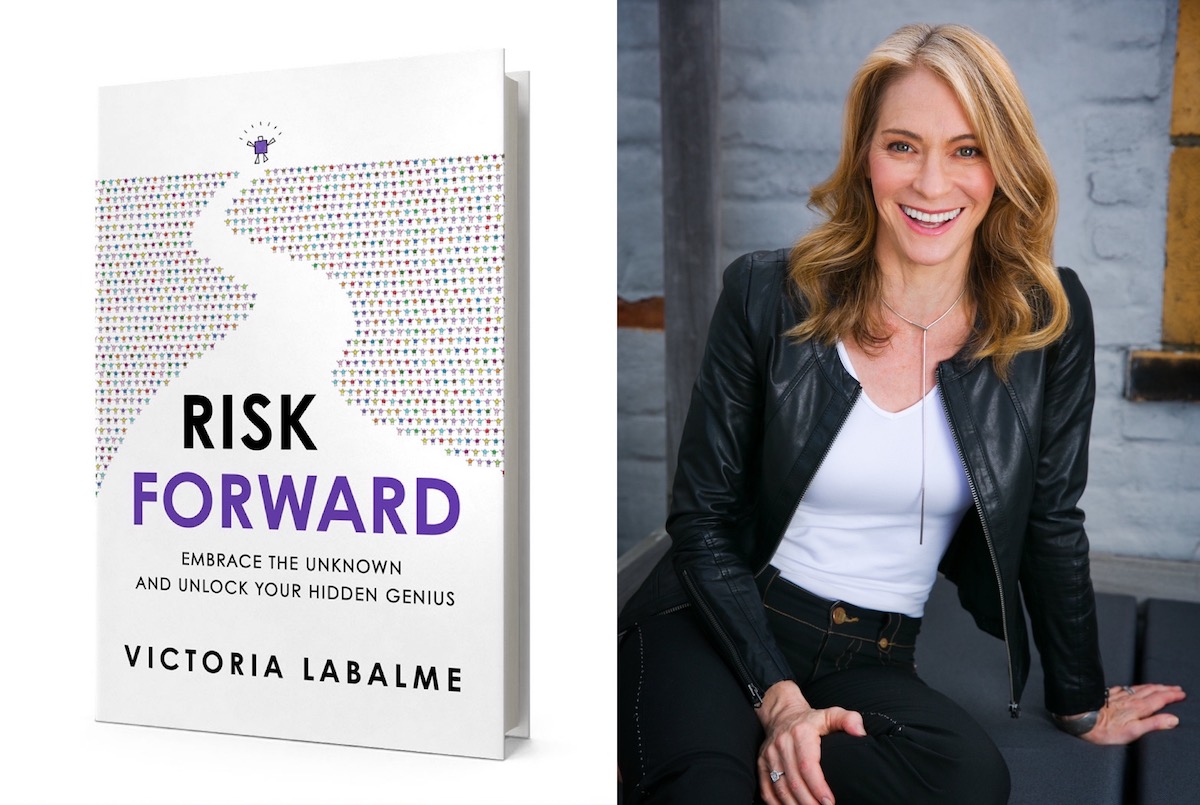

In 2018, I interviewed Labalme and her husband, Frank Oz, about their wonderful documentary, “Muppet Guys Talking,” which illuminated how the collaborative environment established by Muppet creator Jim Henson could be applied to so much more than puppeteering. “The film is really for all types of people—leaders, entrepreneurs, artists, anyone trying to do great work and innovate and create,” she noted, and the same is true of her book. What’s perhaps most surprising about Risk Forward is how cinematic an experience it provides readers, both in its vibrant imagery and engrossing pace. Prior to the book’s release on Tuesday, March 30th, Labalme spoke with me about her approach to writing and illustration, the unforeseen obstacles she tackled on the road to publication and the Risk Forward community she’s already begun to build (you can find all the bonuses readers can acquire for pre-ordering the book here).

Was Pete Docter’s process of “finding the film” when making “Inside Out,” which you reference in Risk Forward, similar to how you found the book?

Absolutely. For many of us, when we have a creative project in our mind, we have some vague sense of what it’s going to be. Sometimes it’s clearer than at other times, and as you get into it, it starts to change. I think that’s actually a good thing. If we tried to make just what we had in our mind, we might be limiting ourselves instead of letting the project tell us what it wants to be. For example, I had first envisioned that the book would be like a souvenir program from a Broadway show, where you have a mixture of photography, text, stories and illustrations. But since early readers of the initial drafts all felt my pen and ink designs that I had added to various pages were much more compelling than the photographs, the project went in that direction.

What inspired your approach to the illustrations?

The pen and ink figures were born, if you will, in the early 90s and I actually trademarked them back then. I had returned to the states from West Africa, where I had been for a few months. I was disoriented in the way you can be after you’ve come back from another country, especially a third world country. It was so shocking to return to our culture, and I spent a few weeks just acclimating. For reasons I can’t explain, I wandered into an art gallery section of a store, and there on the wall was a painting which had these little designs. They were totally different from what my own designs became, but they were so inspiring to my eye that when I came home, I started drawing again. The original figure I drew is quite different than the one that lives on today, which is comprised of a square box body with a square head and triangular arms and legs.

For the early versions back in the 1990s, I had additional geometric shapes and I colored in all the arms and legs. The dimensions were also different. Just like the book, over time they developed into something that was very simple, clear and easily identifiable. After I trademarked the design, I started drawing the characters on various forms of stationery and printed a whole series of cards, some of which I still have today. I made other types of stationary products as well—a calendar, a poster, note pads, mini books and—and over the years, I illustrated some of my teaching handouts with them. Clients seemed to really love them. The characters have their own light and energy, their own spirit and it’s a spirit full of whimsy, wisdom and playfulness.

Those designs are part of why Risk Forward transcends the conventions of what would be considered the book’s genre by making it interactive, much like the books I loved reading when I was a kid.

It’s so interesting you referenced children’s books because when I was growing up, there was a particular children’s book that my sister and I loved. In the early 2000s, a number of publishers and literary agents had approached me about writing a book, because I was on the speaking circuit and because of this, had a built-in audience—what’s called a “platform.” But the agents and publishers who approached me wanted me to write a standard book. I kept saying, “I want to write a book like this,” and I would hold up the children’s book.

They didn’t quite understand—they couldn’t see what I saw—and I suspect some thought I was crazy. But what I meant was exactly what you noted. I wanted it to be an experience and visually exciting. So the book is interactive and highly designed. Every page is different. Each chapter is unique. It’s fun to look at and it’s easy to read. Eventually, I found a publisher who trusted me and let me create based on the vision I had. I explained to them early on how I saw the book, and they were supportive all along the way. For that, I’m so immensely grateful. Coming from a performing arts background, and a theatre and film background, I’m always keen to create an experience and take the audience—in this case, the reader—on a journey.

In the book, you mention Marcel Marceau’s principle of “trusting your own rhythm.” Did that also help you in your process as a writer?

Yes. I built the book—and I use that word very intentionally—in Keynote, which is the Apple software program for slides. It has the same function as PowerPoint on a PC. I was so accustomed to building my presentations using the slide software and format that I built the book in the same way. It enabled me to play with the order of the pages by moving the slide order and in this way, create an experience. Literally like frames in a movie, I could slide around different chapters or “scenes” and “moments” in the Keynote software to create the right flow.

One of the things that I did more times than I can count, just like when you’re editing a movie, is to go back through and watch the flow. I would click through the slide progression to gauge the rhythm, ensuring that I didn’t have too many long chapters. The experience needed that momentum. There were some really beautiful stories and bits that I had to pull out because they clogged the flow. That was incredibly hard, but in service of that larger rhythm, I excised those pieces, and some of those will go in the online “resources” area for the book.

I like how the book has a Circle of Contents™ rather than a Table of Contents, thus encouraging readers to have a nonlinear experience.

I called it a Circle of Contents™ because that’s how I see it. You can go through the book in any order, and to make that possible, I wrote the book so it could be experienced front to back or in any order, at your own pace. It’s written for both types of brains—the logical and the free.

One of the elements I wanted to avoid is that in a lot of books that focus on development, whether professional or personal, there’s often homework at the end of the chapter. Sometimes even the writer tells you not to move on until you’ve done certain work. Of course, invariably as a reader, you finish that chapter and you think, ‘Ah, I’ll turn the page,’ but then you feel a tad guilty. In the case of Risk Forward, I never wanted people to feel bad as that goes against the whole message of the material and because it has no restrictions in how it’s to be read, people are feeling this incredible freedom and ease. It was important that the style of the book matched the message of the book.

You also illustrate the value of not knowing when navigating through a crisis, whether it be 9/11 or COVID-19. How do you see this book helping people through the time we’re living in now?

That’s a great question. One of the first ideas that I share in the book is that it’s okay not to know. Not only is “not knowing” okay, it’s actually rife with possibility. So many of us think we’re wrong when we’re in this phase, but that’s purely due to the culture. As I say in the book, we’re always being asked, “What’s your plan? What’s your goal?” I think the worst thing we can do when we don’t know is to make a decision too quickly. In the book, I call this period of not knowing “the fog” and the book offers readers a series of ways to navigate out of that fog. If you were in an outdoor field of fog, the first thing you wouldn’t do is run. You might hit a tree. You want to find your way out intentionally and the book offers a series of principles to aid you in doing that.

What made you decide to open up about your challenging experience of acting in an episode of “Sex and the City” and the lesson you learned from it?

Any story I tell in the book from my own life involves sharing the mistakes I made. In terms of my experience on “Sex and the City,” even though I only had five lines in that scene—and I’ll keep the story here a surprise for the reader—to this day I still think I never quite got back to my original impulse. I regret the times in my life when I didn’t trust myself—I think we all do—but the older we get, the better we get at honoring those instincts.

Featured prominently in the book is Dave Goelz’s observation from “Muppet Guys Talking” about the nobility behind the Muppets. How did his words resonate with you?

“What is the nobility behind your work?” is a core question I developed for my programs. I’ve asked this question to people around the world and the responses I’ve received are usually statements like, “Helping people communicate and collaborate,” “Improving the health of communities” or “Making the world a better place.” That’s the kind of answer I thought Dave’s was going to be when I posed my “Noble Intent” question to him. But his answer was one I hadn’t seen coming and it also beautifully emphasizes the message of the book.

It’s so easy to look at someone else who has greater success in your field and assume they have it all figured out. What Risk Forward offers and what Dave is basically saying is, “Everyone is figuring it out.” And we do that each in our own way. The book offers people permission and a series of prompts to help them figure out their next steps—whether they’re an artist, a leader, an entrepreneur, a student or recent graduate, someone going through a change in health, relationships or career. The book helps us bring out the best in ourselves and others, even when we’re in a place of uncertainty. Covid certainly taught us all a lesson there. When people say we are now living in uncertain times, I respond, “We’ve always been in uncertain times. It just became more apparent to us now.” Because nothing ever is guaranteed—our jobs, the market, our health, our relationships, the world around us. I learned that on 9/11 when I watched from my window as the towers exploded and then collapsed. I learned it when my mother, who was the queen of health—Yoga, chamomile tea, healthy food and a calm demeanor—was diagnosed with cancer.

I was so moved by your mother’s wisdom, which beautifully articulates how all of us have strived, in one way or another over the past year, to do the best with what we have.

Not only was she a graceful woman—I say she was like a white lily—she was also ahead of her time in so many ways. She received her PhD from Harvard a few days after she got married. She wrote books, she taught, and she later went on to become Associate Director of the Institute for Advanced Study down in Princeton, which is a think tank where social scientists, historians, mathematicians and physicists—including Albert Einstein—developed and created their important work. My mother would always say to me, “Let things unfold.” Years before I came up with the concept of “Risk Forward,” the title of my book was Finding Your Way.

Roger Ebert demonstrated how profound insights could be conveyed in ways that are accessible, and your book is an example of that as well.

People have told me that they’ve found the book profound and thought-provoking, but also whimsical, fun and easy to read. Each word was carefully chosen. I was an English Literature major in college and was specifically interested in poetry. Part of my training in writing poetry was understanding the importance of economy in language. I had a wonderful poetry professor at Stanford, and there was a poem I wrote early on where I described a jazz player on the street in Manhattan. I wrote, “I picked up a small, hard coin and I tossed it in his case,” and my professor said, “You wasted a word there. Actually, you wasted two words, because we already know that a coin is ‘small’ and we know that a coin is ‘hard.’” So I changed it to ‘a cool, moist coin’ to provide two new descriptive words to the concept of a coin. It was a profound lesson in language, and I have been very careful about word choice ever since.

I also studied standup comedy for a few years. Great comedy requires economy of words and excellent structure. There’s a famous quote from Thomas Mann in which he notes, “A writer is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” When I teach speaking skills in my Rock the Room® programs, people will say, “I just like to get up and wing it, and I’m really good that way,” and I always tell them, “You could be a lot better if you had some key structural elements in place.” In Rock The Room®, I show them how to do that.

The many different vibrant colors used throughout the book are, to me, evocative of nature.

Robert McKee, who wrote the book Story: Style, Structure, Substance and the Principles of Screenwriting, refers to what he calls the “image system” of a film. For example, in “Casablanca,” the image system is prison. There’s a scene when Ingrid Bergman is against a wall. Bogart is talking to her, and the light coming through the shades creates a slatted set of shadows, like bars across her dress. The sense of prison also appears when Bogart is at the club standing behind the iron gates. That prison imagery is throughout the film, but it’s very subtle. What’s interesting about the image system for Risk Forward is that I did not create it consciously. Only gradually as I was editing did I start to notice that the majority of metaphors in the book have to do with earth and the natural world.

I noticed that you adapted your “Conveyor Belt” bit of never-ending activities, which is so hilarious onstage, for the book.

Yes, “The Conveyor Belt” went in and out of the book. I thought it was a fun way to illustrate the pressures that can keep us from risking forward. When I perform “The Conveyor Belt” live, I customize the bit for each audience. If it were the same words strung together each time, it would be so much easier. Though the opening and closing of “The Conveyor Belt” are pretty much the same each time, the middle ninety percent is always different. When I do keynotes for different organizations, I interview the core team beforehand and ask, “What are the activities and events of a typical day? What are your acronyms? What do people complain about or make fun of?” Then I custom craft the bit and memorize it. The payoff is that in the first ten or fifteen minutes of my keynote, the audience realizes, ‘OK, she’s done her homework. She knows us.’ And it’s always funny. It’s also the moment when I first win an audience—because they know I understand their world and I’ve done my prep. And they know the keynote is not going to be a typical talking head—it’s going to be an experience.

The exclusive bonuses readers can access when pre-ordering the book seem to connect with your skill in building community through your livestream events.

There are two types of bonuses. We have a special set of bonuses for people who preorder the book and we have another set of bonuses for people after they get the book. Those are housed in an online resource center. Risk Forward is the kind of book that people return to again and again. I also wanted it to be the kind of book that people could read in one sitting, so I took some of the extra material, like the extras on a DVD, and placed that in a special online resources area. And then for those who want to take the Risk Forward experience even further, we also have additional experiences and opportunities.

We have an online community, too, and it’s already thriving. The people in the group are so wonderful. They’re having a great time and they’re from all walks of life. In Risk Forward, everyone’s on their own path.

For more information on Risk Forward and to preorder the book prior to its release on March 30th, click here. You can also visit Victoria Labalme’s official site here.