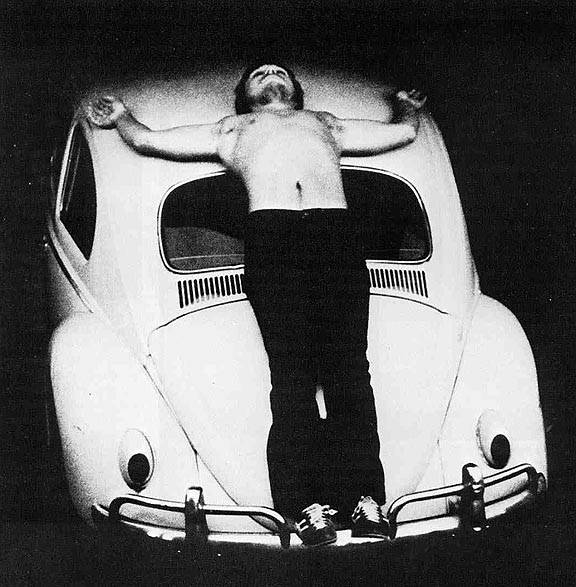

“‘The Volkswagen piece?'” Chris Burden was saying. “Let’s see. I was standing on the rear bumper of a VW bug, nailed to the roof of the car through the palms of my hands. The car was inside a garage, and the spectators were outside.

“The garage doors opened, and the VW was pushed halfway out, with the engine in neutral. It ran at full blast, making a screaming noise. Then the ignition was turned off, the car was pulled back into the garage and the doors were closed. To the spectators, it was well, sort of like an apparition.”

He sipped a tomato juice, plain. This was only his third day back on food and drink (except for celery juice) after a period of 21 days during which he lived, slept and fasted on a triangular platform so high above the floor of a New York art gallery that no one could see for sure if he was really there. Then he had climbed down, and now he was in Chicago, having lunch at the Arts Club and talking about what he would do at 8 p.m. Friday at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Chris Burden is a “body artist,” And at 28, he is one of the best-known practitioners of this strangest and most controversial expressions of modern art. He does things with, and to, his body. And the works, or “pieces,” that result usually are recorded by photographs or videotapes. He defines body art as “an examination of reality, a calling into question of what it is to exist.” His critics have described him as the Evel Knievel of modern art.

Burden is a slight, quiet, almost shy person. It must take an enormous ego to fuel his most difficult pieces. (He has crawled 50 yards through broken glass and then purchased time on a commercial TV station to show a l0-second film of the event every night for a week.) But when he talks about his work, he seems somehow diffident.

“Everything is out there in the world,” he said, “but it is what’s happening inside the mind that makes it real. Most people allow only a certain amount to come in. Perhaps what I’m doing is providing people with the opportunity to let something more in, to stimulate their imaginations.

“When I use pain or fear in a work. It seems to energize the situation. In works with violent or unpredictable elements, the fear is really the worst part, worse than the pain. Getting nailed to the Volkswagen, for example. I had no idea what to expect. But the nails didn’t hurt much at all. It was the effect that was fulfilling.”

In one of Burden’s most famous pieces, he had himself shot in the arm by a friend. He called it his “Shoot Piece.” The bullet penetrated his arm, but that wasn’t the plan, he said: “It was supposed to be a graze wound, but my friend missed. We didn’t even have a first-aid kit on hand. In retrospect, the whole thing seems incredibly stupid. But at the time, you see, we simply couldn’t allow for the possibility that the piece wouldn’t work.”

I asked if it wouldn’t have been safer to have his friend shoot at his right arm, which was, after all, farther from his heart.

“Noooo,” he said, musing. “The idea was not to miss. At first, I wanted the graze wound to be across my rib cage, but my wife talked me out of that. There’s very little pain in getting shot. It’s more of a shock — like getting hit by a truck.”

Burden has not yet had himself hit by a truck, but he has risked his life in a variety of ways. Once he had himself fastened to a concrete floor with copper bracelets around his neck, wrists and ankles. Buckets of water were placed nearby with live electrical wires in them, and then the audience was invited to enter.

“I had absolute faith that nobody would kick over a bucket,” he said. “If they had, I would have been electrocuted. With some of the more absolute pieces, like that one or the piece where we sat on stepladders in a basement filled with electrified water, you have absolute faith. It’s a way of really confronting life and the passage of time and what you think about people. After all, I’m not suicidal.”

Some of his pieces have been almost mystical experiences, he said. During the 21 days he was invisible on the platform in the art gallery, people tried to climb up the walls to see if he was really there.

“My close friends in the art world knew I was there,” he said. “For other people, it was really an experience. Some of them thought it was a put-on. I could hear everything they were saying. One person said to his friend that being in that room was almost spiritual – because I could hear them and didn’t respond, and that colored how they spoke and thought.”

As his master’s thesis at the University of California at Irvine, Burden had himself locked into a locker measuring 2 by 2 by 3 feet. The locker directly above him contained five gallons of water, and the locker below had an empty five-gallon bottle. He stayed in the locker for five days, and during that period, his piece became wildly controversial on the campus. People came to talk to him through the grill at all hours of the day and night.

“It was like hearing confessions,” he said. “People couldn’t see me, but they knew I was there. They told me about their Army experiences, about things they’d done they were proud of, or ashamed of. I was like a box with ears and a voice. That was interesting. The rest was pretty hard. I was in a fetal position. I could scoot around a little, but I couldn’t bend my knees. The cramps were always there.”

Burden said it’s always his violent or sensational pieces that get talked about: “Even I talk about them more, because they’re . . . well, easier to explain: But one of the most interesting things I did was the ‘Disappearance Piece.’ I disappeared for three days, and nobody knew where I had gone.

“Actually, all I did was check into a motel. But it was a funny thing: I didn’t feel I could do anything during those three days. I didn’t read, or eat or even watch television. How could I, when I’d disappeared?” Burden’s reappearance at the Museum of Contemporary Art at 8 p.m. Friday will be part of the museum’s current, and controversial, survey of recent body art.

I can tell you that admission is $1.50 for adults, $1 for students and free for museum members, but I can’t say what Chris Burden is going to do. Perhaps he doesn’t even know yet, Toward the end of the lunch, Ira Licht, curator at the museum, asked if Burden could give any indication of how long his piece would take on a scale of from 5 minutes to 21 days, say. “No, I can’t,” Burden said.

“It’s not a question I’m supposed to ask?” Licht said. “Right,” said Burden. “Something that lasts 45 minutes is not necessarily richer than something lasting 5 seconds.”

“But a lot of our audiences come from the suburbs,” Licht said. “What if they’re a few minutes late and the piece is already over?”

“Well,” said Burden, “you can’t please all of the people all of the time.”