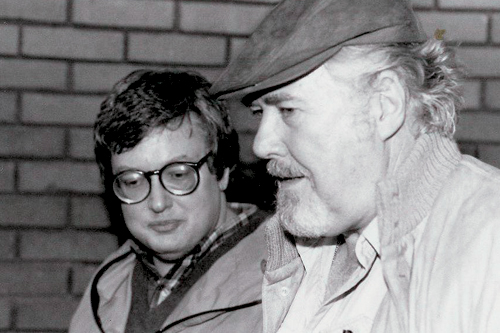

He’s a big, cheerful, bear-like man with the ability (unusual among film directors) to poke fun at his own work. “I stay with my films all the way,” says Robert Altman. “Through the editing, through the post-production, all the way until they’re in the theater and really failures.”

Laughter. Altman is sitting on a table in front of a room jammed with University of Iowa students. He has come to Iowa City to take part in a film festival named Refocus and to preside over the Midwest premiere of his new movie, “Thieves Like Us.” It’s an awfully good movie the story of a lanky young Depression bank robber and his sweetheart but it hasn’t been very successful at the box office in the only two cities where it has played, New York and Washington.

Altman tells the students he’s inclined to blame the distributor, United Artists. The movie was launched with a lot of good reviews, including high praise from the influential Pauline Kael, but it was booked into an out of the way Manhattan theater. “And all the ad campaign says is that the movie’s a masterpiece,” Altman complains. “Would you go to a movie that was hailed as a masterpiece? Already it sounds like hard work.”

Altman’s previous film, “The Long Goodbye,” also suffered at the hands of United Artists. “They were promoting it as a hard boiled detective movie,” he said. “It was anything but. I tried to take Raymond Chandler and do what he did. He paid no attention to his plots. He used his action as an excuse to hang about a hundred thumbnail sketches on. That’s what I tried to do. My obligation wasn’t to the plot of his book, but to the spirit of his book.

“There’s a famous story about the time when Leigh Brackett and William Faulkner were doing a screenplay based on Chandler’s ‘The Big Sleep.’ They got, to a point where they couldn’t figure out what happened. They called up Chandler, who was working over at Columbia, and he asked them to wait a minute and he’d look at the book himself. He came back and said, ‘My God, I can’t figure out what happened either’.”

“The Long Goodbye” was released a year ago and bombed. It never even opened in New York until last autumn, some six or eight months after its California premiere. But for the New York opening, Altman personally junked the old ad campaign and came up with a new one featuring illustrations by Mad magazine regular Jack Davis. The new campaign made the wry nature of the movie clear, and it did well in New York and had a comeback nationally. “But nothing like it should have had,” Altman says. “That should have been a $20 million picture. Even United Artists admits it.”

Altman labored for years on several television series, especially “Combat,” before moving up to theatrical features. His first great success was “M*A*S*H,” an enormously profitable 1970 release. Since then he has had great critical successes with “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” and “The Long Goodbye,” and mixed reviews for “Brewster McCloud” and the elusive “Images.” But no big successes at the box office.

“I’d better make some money for somebody pretty soon or I’ll be out of business,” he said, but not too cheerlessly. Like the characters in his movies, he seems to go through life with a kind of calm faith that things will somehow turn out all right. In most of his movies, of course, things don’t turn out all right but the characters think they will.

“All of your films since ‘M*A*S*H’ have been depressing,” one student said.

“You didn’t find M*A*S*H’ depressing?” Altman said “Then I failed.”

He thinks his new film, “California Split,” may be a commercial breakthrough. He did it for Columbia, which is laboring to come up with the right ad campaign, and it is a movie about two junkie professional gamblers (George Segal and Elliott Gould).

“The entire movie is shot with a very slow, almost invisible, zoom in,” he said. “The idea is to involve the audience in gambling, to pull them into the story. The movie is totally authentic in all of its gambling sequences. For a poker game in Las Vegas, for example, we refused to use stacked decks in order to rig dramatic poker situations. Instead, we used real poker players in a real game. And we watched them so closely that even if you don’t play poker you can understand what they’re trying to do.”

Altman pays a lot of attention to the look of his films, he said, and works closely with his cameraman. “For ‘McCabe and Mrs. Miller,’ we wanted an antique sort of look, and I think we got it,” he said.

“For ‘The Long Goodbye,’ we did an interesting thing. The camera never stopped moving in that film. We’d lay our camera tracks along one side of the room we were shooting in, and I’d have the grip push the camera platform very slowly from one side to the other, then back again. At the same time, the camera would be moving, very slowly, up and down. And, very slowly, zooming in and out. All the time. The idea was to make the audience feel like eavesdroppers, always craning their necks to see what was happening.”

“Thieves Like Us,” a very good film, dreamlike and poignant with sudden flashes of violence, stars Keith Carradine and Shelley Duvall. They’ve both worked for Altman before. Carradine was the kid who, to his own vast surprise, got shot on the bridge in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller.” Duvall was the young girl who went to work in Julie Christie’s whorehouse in the same movie, and she was also in “Brewster McCloud.”

Altman brought the two of them along with him to Iowa City, and they answered questions about acting in general and, especially, acting for Altman. Carradine comes from a theatrical family (his father is John, his brother is David). Shelley Duvall never acted before Altman discovered her in Houston; to a question about her acting methods, she replied rather shyly that she’d never even seen a stage play until a month ago in New York.

Altman’s films sometimes have the feeling of improvisation, but the three of them described his method this way: He starts with a script that gives a good notion of what’s wanted, and then on the set he works with the actors in a broad improvisation of the material that eventually — he didn’t say just how — locks itself in. “And when it’s set, we shoot.”

He prefers to do scenes from beginning to end, without interruption, even if all he really needs is a close-up. And he never rehearses. “Well, once I called the actors together four days early for a rehearsal,” Altman said, grinning, “but when they got there I was very embarrassed because I didn’t know how to rehearse.”

Nor does he know how his methods on the set differ from other directors. “I’ve never seen another director work. In fact, I’ve never been on a set other than my own. All I know about movie directors is what I see in the movies.”