The strength of a

great performance should never be underestimated. They can be intoxicating to

the point where everything else appears better at first viewing than it does

upon reflection. In the case of

“Suffragette,” Carey Mulligan’s performance as a worker-turned-activist

is so passionate that the whole project suddenly feels more involving. But soon

after the film ends, when one leaves the theater and tries to take parts

of the movie with them, that performance high dissipates, as nothing else here

really compares.

“Suffragette” is inspired by the movement by British women in the

early 1900s to earn the right to vote. When their cause was not heard,

they turned to civil disobedience, throwing stones at glass windows and bombing

mailboxes. They became public enemies, were jailed for their protests, and

responded to this treatment by going on hunger strikes. To keep their voices

heard, they would repeat this cycle, abandoning their families and their

jobs, while trying to support each other. Director Sarah Gavron introduced

the film by saying she has been trying to make this film for ten years. It’s

a saga that needs to be told, especially as civil disobedience

still proves the best, and most confrontational way to get the world’s attention.

Mulligan stars as Maud

Watts, a laundry worker, wife and mother who has been raised in the factory.

Maud has also been raised to not question the roles put upon her, and only

express discomfort, not outrage, when her slimy boss gropes her in the factory.

Through the women she knows from the factory, she becomes involved in the

suffragette movement. When we meet the rebels, they have evolved past peaceful

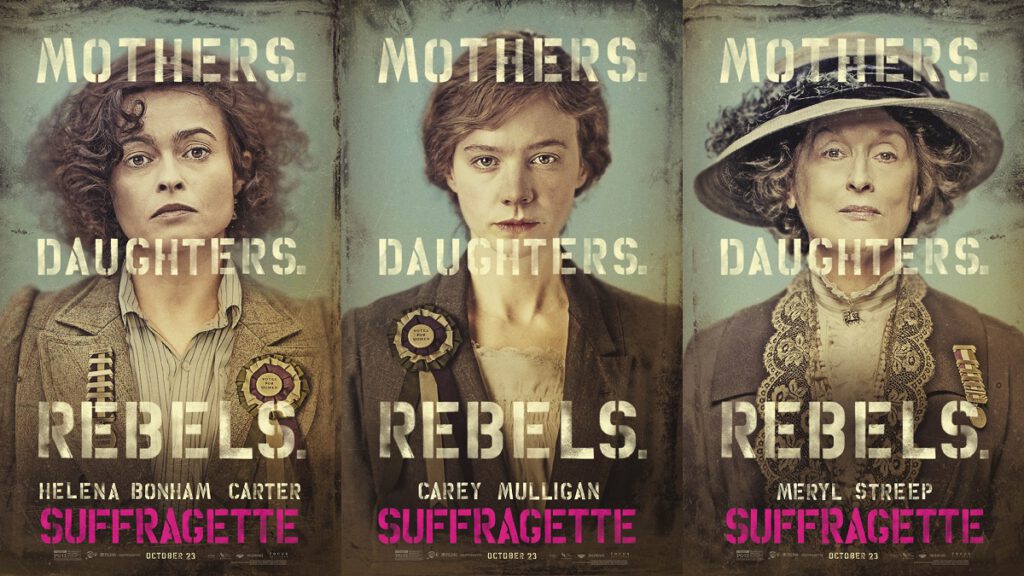

rallies into civil disobedience. Protestors led by Edith Ellyn (Helena Bonham

Carter, not given much to do) follow the words of ringleader Emmeline Pankhurst

(Meryl Streep), and take to the streets, where the likes of authority figures

like Inspector Arthur Steed (Brendan Gleeson) surveil them.

Maud is written

efficiently enough, but her journey only comes to life with Mulligan’s inner

workings. Her precisely expressive face and emotional gravity show the natural,

complicated progression to becoming a full-fledged suffragette, and we are

right there with her. Her soulful gazes achieve more without words than the

script ever does with dialogue. It’s enough to make the script’s slices of plot

feel more urgent than they actually are.

The work of Mulligan

even affects other actors and making their moments better. Ben Whishaw’s

performance as her husband Sonny is even more tragic when he has to destroy

someone like Mulligan’s Maud because genre roles say so. The same can be said

for scenes in which Mulligan acts opposite her on-screen son George, played by

Adam Michael Dodd. They have a couple scenes together with an unexpected

emotional power; I was hit harder by a scene in which she tries to make her son

laugh, while she stands soaked in the pouring rain, than any moment in

Telluride favorite “Room.” It is a genuinely heartbreaking passage in

this story.

It is when “Suffragette”

lacks “The Mulligan Effect” that it displays its clumsiness and limited nature.

Its handheld cinematography is fitting, but the editing can be pretty rough.

When rallies becomes violent catastrophes, they’re more often than not visually

incomprehensible. The same can be said for how it chops up Streep’s

heavily-anticipated cameo, distracting from an already klutzy attempt at vigor

(her accents have had better days).

Touching upon the

history of the suffragette movement doesn’t make for a full script in Abi

Morgan’s adaptation, especially with the complicated, decades-long battle that

would require coverage of more than just a single victory. After showing these

women in action, eventually “Suffragette” just ends itself,

concluding that it has goals no bigger than to mention a great cause, show what

it was like for an outsider, but then turn the rebellion’s fervor into a

crowd-pleasing rally. With or without its leader, “Suffragette”

doesn’t have enough power to spark its own movement.