America wasn’t created with the existence of the Black man in mind. All of that jazz about “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness” protected the hopes and dreams of white men seeking freedom from their tyrannical giant across the pond. However, those same privileges were never meant to be extended to the Black bodies slaving in the fields to grow America into an empire.

Today, in the 400th year since the first Africans stepped foot on this land as slaves, the Black man still suffers in the America system. In fact, throughout the last 300 years, America dreamed up ways to beat the Black man into despair whenever there was an opportunity to better himself.

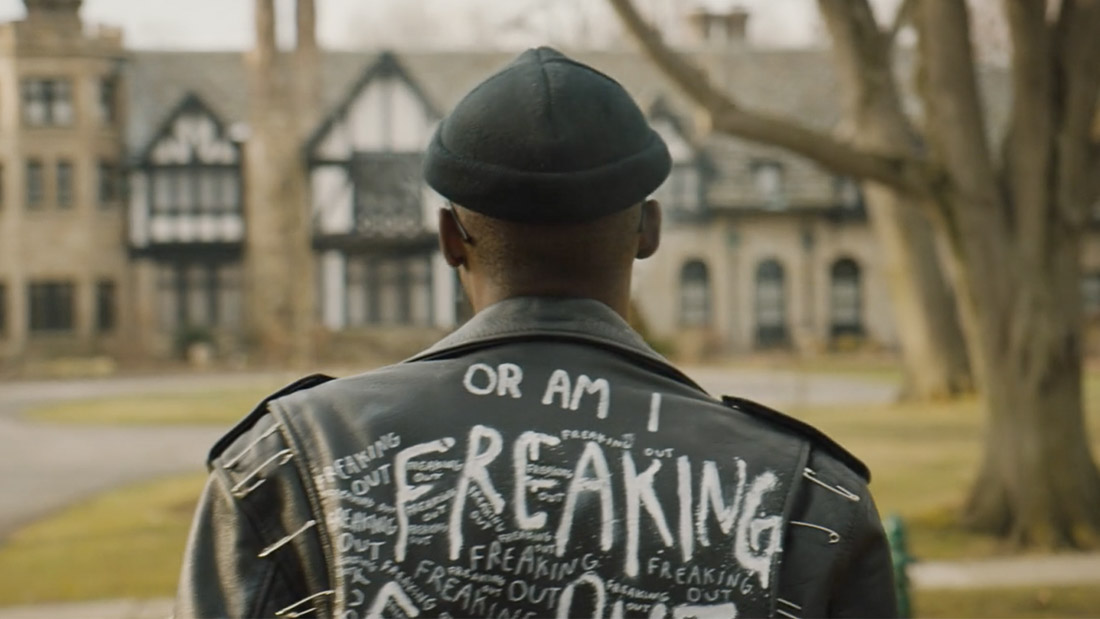

It’s this hopelessness that bleeds through director Rashid Johnson’s heartbreaking film adaptation of Wright’s 1940 novel, Native Son. With Suzan-Lori Parks as screenwriter, the film version of “Native Son” breaks away from crucial plot points in Wright’s novel to produce a suspenseful critique of the painfully inescapable fate of a Black man trying to do right in a system that’s demonized and oppressed him since birth.

“We all know that stories like these are still happening today. What we lack are the tools to have conversations about these stories,” Parks said during a Q&A session at the film’s Sundance premiere.

“Hopefully, this [Native Son] will give us some of these tools,” Parks added.

Set in Chicago, a longtime playground for segregation and Black inequities, 20-year-old Bigger Thomas is a bright kid who is caught between two completely different worlds, one where he constantly has to prove his Blackness and manhood through his allegiance to street life, and another where code switching and being the “good Negro” is required to keep a high-paying chauffeur job with his rich, white North Shore employer.

Ashton Sanders (“Moonlight“) makes us fall in love with Bigger’s charm. He’s a super witty Black dude who loves punk, paints his nails, listens to Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, and reads Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. It’s Bigger’s otherness, and unapologetic drive to be himself, that we root for early in the film. It’s also those character traits, though, that lead to his demise as a Black man.

“It wasn’t until Big started trying to play by the rules that the shit went down,” Parks said.

Bigger doesn’t want to fall into the same stereotypical street life trope to which other young Black men succumb. His only other option is to work for the white man, which isn’t an appealing choice to Bigger, a free spirit of sorts. But when do Black men, in a racist American system, ever have the option of being a free spirit? When his mother’s boyfriend gets him an interview to be a driver for Henry Dalton, he puts on his “good Negro” face and wins Dalton over.

As with any job in white America, there are rules and expectations. Bigger must live at Dalton’s North Shore home, where his blind wife and activism-driven daughter live. Also, Bigger can only use the back staircase to get to and from his bedroom – the rest of the house is off limits.

Their daughter, Mary, immediately takes a liking to Bigger, asking him to drive her to the People’s Freedom Movement meetings instead of school, and to bars and druggy parties with her boyfriend. It soon becomes a recipe for disaster, with Bigger having to do whatever is necessary to satisfy Mary while keeping his job.

Full disclosure: I haven’t read Wright’s book. I plan to now after watching this film. Purists immediately pointed out major flaws and deviations from the book, which they saw as an attempt to build more compassion and sympathy for Bigger’s character. Parks, though, said she felt it was more important for the film to speak to the experiences of a Black man in today’s world than to follow Wright’s novel word-for-word.

“We’re just rolling that wheel that he [Wright] invented, rolling it forward,” Parks said.

It’s a hard watch, for sure. But it’s definitely a must-see.