Editor’s note: Sara Alexandra Pelaez is one of three recipients of the Sundance Institute’s Roger Ebert Fellowship for Film Criticism for 2016. The scholarship meant she participated in the Indiewire | Sundance Institute Fellowship for Film Criticism, a workshop at the Sundance Film Festival for aspiring film critics started by Eric Kohn, the chief film critic and senior editor of Indiewire.

Biographical documentaries were something of a vogue presence this year at the Sundance Film Festival. Over a dozen titles were dedicated to stories of individuals with hefty cultural significance, and upon viewing them I noticed a factor that heavily influenced how these films played: whether or not the subject was alive to tell their tale. The more cogent films expanded upon the gray area of a person and did not cede to just praise and sympathy. I found that the more compelling biographical docs were produced when the subject had passed on, though there were notable exceptions.

Documentaries with subjects who are no longer alive elicited more imperative urges of empathy, in which the viewer desires to understand the subject as best as possible, without the subject’s firsthand perspective. With this, the film can easily fall into a distorted representation of the individual; whether it glorifies them or condemns them is a tricky balance of which directors have to be wary. The documentaries “Jim: The James Foley Story” and “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures” both stride across this tightrope with undeviating confidence, both persisting on developing upon the individual’s gray area, the part that makes the subjects human and empathetic candidates. Meanwhile, a doc like “Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You” shows little grace by becoming a black and white portrayal.

Concerning “Jim” and “Mapplethorpe,” there are generous amounts of talking heads from family members, close friends and others in their fields. With each of these interviews, there are definitely moments of adoration and mourning, but the people also expand upon the subject’s faults. Both of these films have rich interview segments that befittingly expose the humanity of the two men in their respective films.

“Jim: The James Foley Story,” released on HBO on February 6, is about a real stand-up guy from New England, who became a conflict journalist. He went overseas to Libya and Syria and was taken hostage before when he was publicly executed by ISIS. In the film, all of Jim’s family members express extensive frustration with how Jim habitually returned to such dangerous environments. As much as Jim loved his family, after his first trek in Libya he could not sit still in a suburban lifestyle. One of the fellow hostages that spent two years with Jim comments on how the two would take turns massaging one another. He honestly admits Jim simply was not cut out to be a masseuse … at all. Faults are not the only way to express humanity. An accompanying conflict journalist and friend told the story of a lucky lighter her and Jim had shared. The cigarette torch had the Islamic Evil Eye printed on it to ward away malevolent forces; the trivial object became a superstitious emblem, a literal beacon of hope. This sentiment is ripe for empathizing.

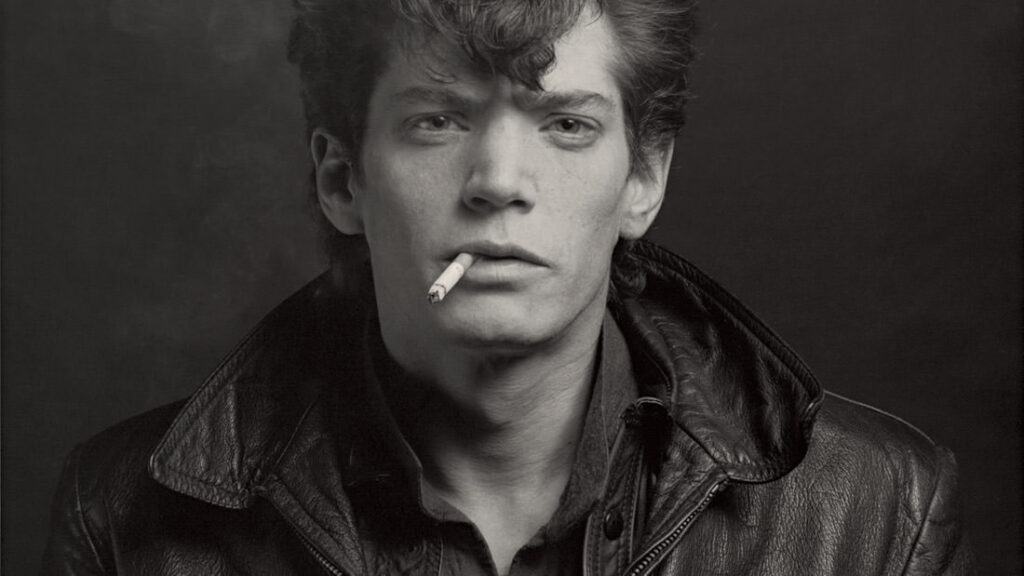

The contributions in “Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures,” scheduled for release in April on HBO, are even more critical of the subject’s character, partly due to him being less apt for compassion than James Foley. Robert Mapplethorpe was a controversial black-and-white photographer from New York City, known for celebrity/self-portraits, nude models (both sexes), flowers, homoeroticism and BDSM. He was egocentric, offbeat and savagely ambitious, characteristics confirmed with input from family, past lovers, and colleagues. One of his college friends from Pratt Institute discusses how Robert had a pet monkey that would perch on his shoulder. He elaborates upon how devastated Robert was when his exotic companion passed away (then he used the monkey’s skull to complete a final for one of his classes). Mapplethorpe’s younger brother, Edward, took on photography as a profession, and it immensely bothered Robert as he did not want to share his last name, and forced his brother to take on another. Edward discloses how he hoped to earn his older brother’s acknowledgement, but that day never came.

Another interesting facet of the documentary is that there is only one instance where Robert is shown speaking with video and audio in sync. All other clips of his voice are edited to narrate over photographs of his life. This removed aspect of his depiction flawlessly supplements his mysterious, private disposition. The filmmakers also incorporate an interesting idea to introduce the interviewees: they put a camera frame around them and then “take a photo” to transition to the next cut. This allusion is elegant and falls in congruence with the subject.

Other biographical documentaries at Sundance strain under the pressure of a subject who could tell their own story, as if there was an invisible net that protected producers from asking their subjects the real questions. The film “Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You” movie becomes black and white, despite the plentiful gray areas to explore that would have made Lear much more commendably human. When discussing his days as a WWII pilot, Lear admits to not caring if the bombs he was dropping missed the target and killed innocents. Norman Lear, this laudable humanitarian who humorously brought social issues into American homes, did not care if he killed innocent people? And what happened with his wonderful activist wife Charlotte? They were in such a happy marriage, and then she committed suicide. There is so much to investigate within a Norman Lear doc, and instead viewers are spoon-fed “He’s the most influential producer in television! He’s just like you!” It feels as though the writers did not make a conscientious decision to fully expand upon his personal life nor his career; both are elaborated on, but not to a satisfying extent.

At least the documentary “Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper: Nothing Left Unsaid” lives up to its name. Vanderbilt eagerly articulates her regrets, flaws and mistakes from her youth. And though she shares a similar timeline and age to Norman Lear, her biographical documentary goes miles further into her truth and tragedy. Contrast to Lear’s bio documentary, which feels safe. In a documentary filmmaker’s panel, Heidi Ewing, the director of “Norman Lear,” verbalized how she specifically did not want Lear nor his children to be in the editor’s room at all during post-production in an effort for them not to influence the film. For films like “Norman Lear,” they might as well have been.