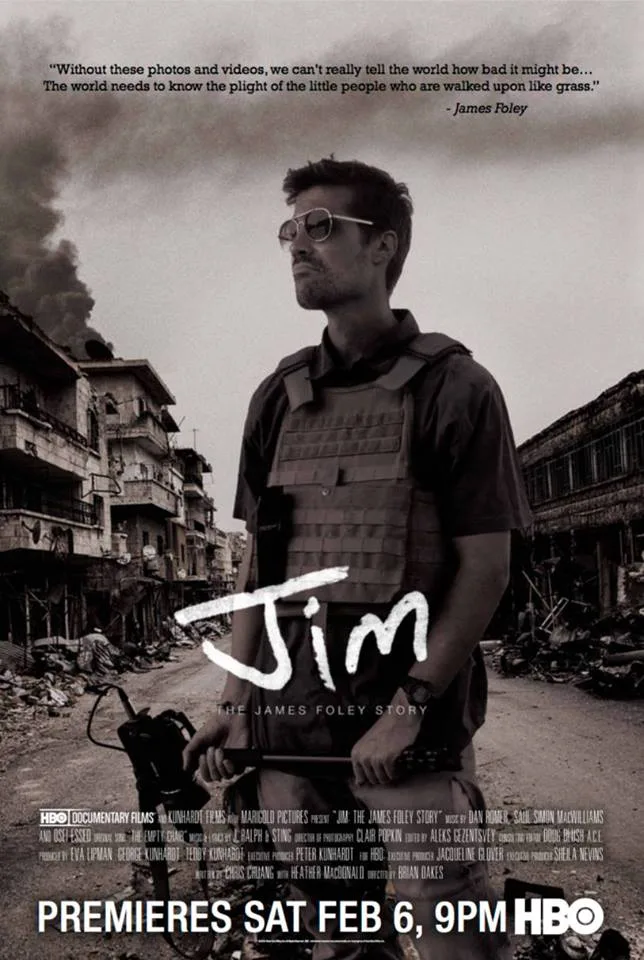

We all know the image. It’s when many of us first heard the acronym ISIS. It’s a still of a man in an orange jumpsuit with his executioner standing behind him in the desert. The man is James Foley, a conflict journalist who was kidnapped in Syria and beheaded in 2014, the video of that horrible act travelling the world as a pronouncement of a new international threat. Brian Oakes’ “Jim: The James Foley Story,” an Audience Award winner at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, premiering on HBO this Saturday, February 6th, reclaims that image. It turns it into more than a tool of terrorism, fully capturing the life of a man who knew he was at risk every time he went out on a job. Directed by an old family friend, “Jim” is a moving portrait of courage, but it is most of all a concerted effort to take back the life of James Foley.

Oakes accomplishes this by speaking to three distinct groups of people—Jim’s family, Jim’s colleagues and Jim’s fellow prisoners. Jim’s family, who often refer to the director by his first name indicating their high comfort level with him, still struggle to understand him. Why would he continue to put his life at risk covering stories in war-torn areas? As stories of kidnapped journalists and embedded reporters being killed continue to proliferate, his family tries to relate to a man who always felt like he needed to be doing something. He would come home, but be restless enough that he had to go back out again. His brothers, father and mother do a phenomenal job of coloring in the emotional details of Jim’s life, letting us get to know him in the way only a family can. It’s remarkable how open and honest they are about their loss.

But a family only knows so much about you, and Oakes’ documentary adds another layer in the way the director interviews those who spent time with Jim in the field. We hear stories about his work ethic, his kindness and his empathy. He’s the kind of man who on doing a story about an under-funded hospital in Syria (in which they were transporting people via cab to the facility), he raised enough money to get them an ambulance. As sketched by his colleagues, Jim was a quiet man who felt like he was doing good by shining lights into dark corners of the world. His work ethic really comes through in these chapters of the film. The people who knew him in the field come to life when they talk about him.

“Jim” transcends typical talking-head documentary when Oakes gets to interviewing the people who were held captive with Foley in Syria. They speak of a man who sacrificed himself for others, always trying to look past the horror of his situation. He would create games for them to play in captivity, and, again, these men who spent days and nights in physical agony speak glowingly of a man who changed their lives simply by being a part of it. As captured by “Jim,” James Foley was a man who impacted everyone he met, whether he did so in the comfort of his family home, in the field, or in captivity.

“Jim: The James Foley Story” is undeniably, primarily a talking-head documentary—a series of interviews more than anything else—and that’s a type of non-fiction filmmaking that critics are increasingly tiring of, with good reason. We need new ways to tell true stories other than through interviews. However, I’m more forgiving of it here for a few reasons. Not only is Oakes’ interview approach—the three different groups—more deliberate than a traditional then-this-happened documentary, but it’s an appropriate style for a movie about a man whose greatest impact was on the people he met. And so we hear from those people. In doing so from three definitive angles—family, work, captivity—we get a full picture of a man. Not a victim in an orange jumpsuit turned into a symbol. A compassionate, caring brother, son, friend, colleague and journalist.