Musical films have always had a home at Cannes. From concert films to biopics to rock docs, these are often a respite from the slow-burn art cinema that occupies much of the slate. Jacques Demy’s masterful film “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” remains the only true musical to take the Palme d’or—though, technically, it received the first Grand Prix du Festival International du Film, joining the likes of magnificent films like Altman’s “MASH,” Coppola’s “The Conversation,” Antonioni’s “Blow-Up” (with the Yardbirds playing a prominent role!) during a 10-year period when the top prize of the fest was changed.

A few years ago “Rocketman” had a splash premiere, complete with Elton John and the film’s star Taron Egerton serenading the black-tie crowd in the Grand Lumière. Having just walked down the beach to arrive at my press screening of that film, I had the most surreal experience of realizing that the “I’m Still Standing” video that is mirrored in the film’s climax was shot on the very path that I strode, images I’d seen since early childhood now retroactively made sense of as I recognized the Carlton Hotel’s beachside strip.

Rob Reiner was in town this year to show “This is Spinal Tap” on the beach to an appreciative public crowd, and it was tied in part to the announcement that a sequel of sorts in the works. I, for one, cannot wait to take another bite of that shark sandwich. Meanwhile, the 4K restoration of “Singin' in the Rain” played at the Agnès Varda theatre, a slight downgrade in screen size from the usual Warner Bros. Showcase where I saw likes of “Unforgiven,” “2001: A Space Odyssey,” and “The Shining” on the superior Debussy setup.

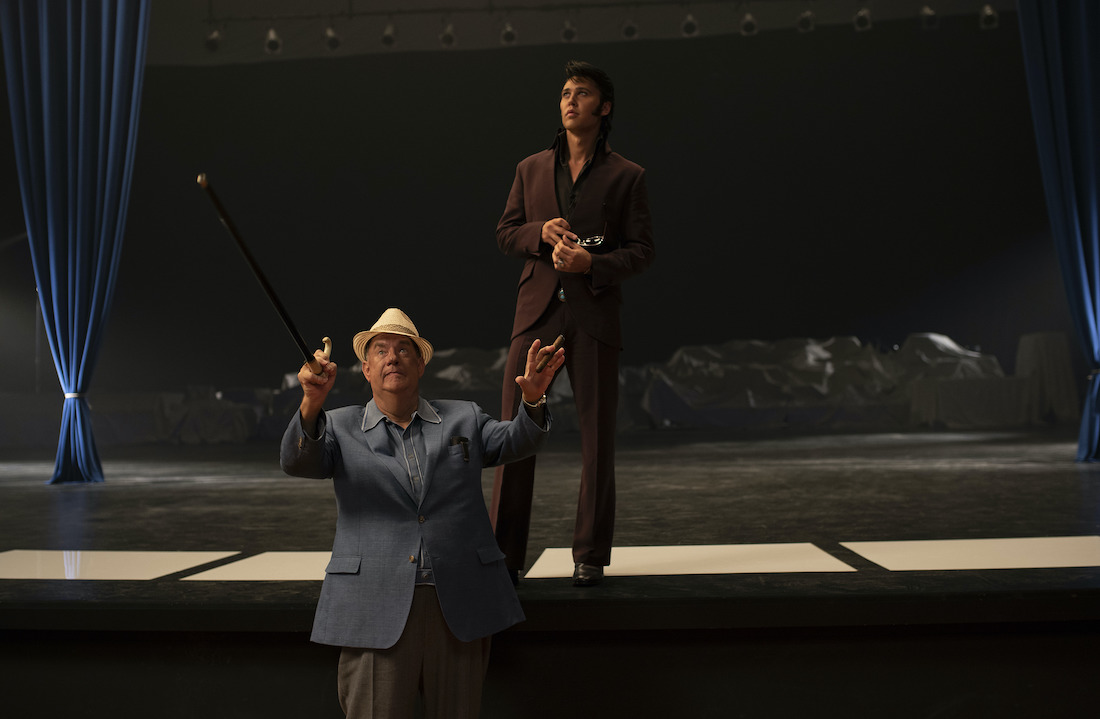

Speaking of WB, their splashy contribution to this year’s fest was Baz Luhrmann’s ecstatic “Elvis.” From the opening shots you know you’re being thrust into one of Luhrmann’s kinetic film worlds, with diamond-encrusted logos spinning in kaleidoscopic fashion and the music thumping away. While not quite as narratively sophisticated as “Rocketman,” “Elvis” does well to surpass the schlocky stereotypes and tabloid fodder to try and get to the heart of the man and his music. Similarly, his relationship with the mercurial Colonel Tom Parker, played by Tom Hanks uttering a Dutch-inflected Southern drawl that’s both impressively precise and will be off-putting to many.

Yet it’s Austin Butler’s uncanny Elvis that’s truly the center of the show. His physicality is extraordinary, going beyond the regular impersonator vibe and seemingly inhabiting the man both in terms of his charisma as well as his extraordinary physical presence. The way Elvis’ music is messed with proves beneficial, reminding younger listeners especially of the explosive urgency that the vintage recordings may not achieve for those who have had such moments of experimentation and genre-blending baked into 75 years of rock ‘n’ roll’s evolution. I compare it to how David Milch uses filthwords in “Deadwood,” amplifying language of contemporary impact to elucidate how these things felt at the time.

Yes, “Elvis” is about a singular figure, but more than that it’s a celebration of a particular time of musical expression, when the entirety of Presley’s own musical gaze was firmly placed upon gospel, country, blues, and other music whose delineation would only become further solidified by the institutions of recording and transmission. Luhrmann’s trademark mash-ups remind us that the barriers are arbitrary if not counterproductive.

The man that followed Presley’s reign at Sun Records in Memphis, and whose own success was initially financed by the RCA deal that saw Sam Phillips finally able to showcase his retinue of artists on a national scale, is documented in Ethan Coen’s “Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind” documentary. Along with his wife and editor Tricia Cooke, the two have taken archival interviews and concert performances to weave a relatively chronological overview of the man known as “Killer.” The big hits are here, with clips familiar to any fan of early rock ‘n’ roll, but it’s the other, more obscure elements, particularly from his later “country” career, that may be more of interest to long-time fans.

The film deftly interweaves these musical and interview moments, buttressed by Lewis’ compunction for laying it all out when discussing his life and career with journalists. The salacious moments, including the U.K. reaction to his teenage bride, are explored directly. Similarly, his other career missteps and faltering asides are documented, including a bearded Jerry Lee talking about his upcoming role playing Christ (I, for one, would welcome a late 1970s inclusion of him in a rock musical version, but that’s perhaps my own bias showing through). Coen’s film a good introduction to the man, and even long-time fans should be pleased by the accessible yet interesting telling of the man’s musical life.

Finally, there’s Brett Morgen’s “Moonage Daydream,” a wondrous, dreamy, ambitiously experimental take on the music doc formula. Stylistically borrowing from David Bowie’s own visual and auditory output, the film dances between disparate timelines of a decades-long career, changing in mood and tone almost as often as the musical artist changed costumes.

In describing the movie I’ve found the easiest shorthand is to reference the last act of Kubrick’s “2001,” which it must be remembered became a massive box office success in part because of a promised cinematic “trip.” Above all else Morgen has created a film that’s to be experienced on the biggest screen possible, and my experience of sitting dead center at the Grand Théâtre Lumière during the midnight world premiere will never be forgotten.

Swirling images, animated shapes, and a wide assembly of stock imagery collide with images of Bowie drawn from concert footage, music videos, and even his own experiments with filmmaking. At times the film settles down to simply revel in a performances, with D.A. Pennebaker’s justifiably revered “Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars” being a repeated touchstone. Yet it’s the way that Morgen strips the songs down to their constituent elements that impresses the most, allowing a unique marriage of interview words and musical fragments to merge into a new, vital work scored by Bowie and his musical collaborators.

This need not be a definitive Bowie documentary that tells his full story, and I’d welcome one that would shy away from some of the more complicated aspects beyond the image he wished to present to the world. That film may come, should come, but no penalty should be accorded to this obvious celebration of the man. That being said, by allowing the contradictions to remain intact, to have Bowie essentially arguing against himself as he shifts justification or description of his art over many, many years, you at least get a glimpse under the mask of the man. You recognize like many of the pop musicians of his era that his interactions with the press were for the greater purpose of shaping his communication to an audience.

I cannot overstate how powerful an experience it was to see “Moonage Daydream” on that giant canvas, and whether you’re a Bowie fanatic or simply one open to a remarkable feat of documentary filmmaking, I strongly encourage all that are able to view “Moonage Daydream” on the biggest screen possible, including the IMAX screens that are planned for the film’s theatrical run. It’s Bowie at his biggest, Bowie at his best, all thanks to Brett Morgen and his remarkable talent in elevating already iconic artists in ways few other filmmakers (Pennebaker a leader among them) have been able.