I feel sorry for the Earth’s population

‘Cause so few live in the U.S.A.

At least the foreigners can copy our morality

They can visit but they cannot stay

—Bad Religion, “American

Jesus” (1993)

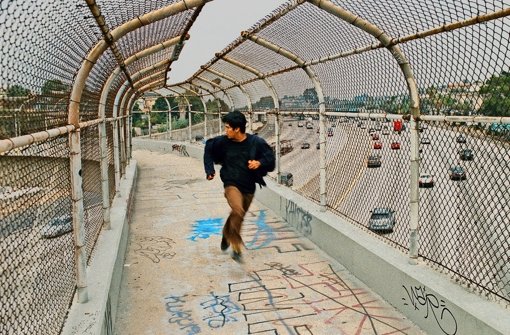

Border incident: as the midnight sky blazes with New Year fireworks, a young

man sprints full-pelt across the wide expanses of a colossal, concrete

river-bed, small rucksack jiggling his slender shoulders. Behind him, Mexico,

land of his birth; ahead of him, California, the state where he grew up and to

which he ardently longs to return. He’s Nero Maldonado (Johnny Ortiz), whose

negotiation of frontiers both geo-political and personal is the focus of

Iranian writer-director Rafi Pitts’ fifth fiction feature “Soy Nero.”

On paper, this was perhaps the most promising of the eighteen contenders for the

2016 Golden Bear: Pitts debuted in Berlinale competition a decade ago with his

international breakthrough “It’s Winter” (2006) and tried again in

2010 with “The Hunter” (2010). Both went home empty-handed, but

Pitts’ reputation was steadily growing. “The Hunter”—spare study of a man partly defined

by and partly at odds with his geographical/political contexts—starred Pitts

himself as an ordinary individual pitched into a cycle of violence by the

killing of his wife. It obtained art-house distribution in numerous major

territories including the USA, Australia and most of Europe.

Two years later, Pitts scored a small but crucial role as a consular official in

Ben Affleck’s Best Picture winner “Argo“—controversies over which have effectively prevented him from

returning to his homeland. The half-English, London-educated Pitts—a

familiar face around the festival circuit—has now become not so much

stateless as a truly international, frontier-transcending figure. Likewise, his

films: German-French-Mexican-American “Soy

Nero” (Spanish for “I am Nero”) was shot by Greek

cinematographer Christos Karamanis (“Chevalier”); edited by France’s

Danielle Anezin; co-written by Pitts and Romania’s Razvan Radulescu.

The latter was also responsible for Cristi Puiu’s epoch-shaping “The Death

of Lazarescu”, Cristian Mungiu’s Palme d’Or laureate “4 Month 3 Weeks

and 2 Days”, and “Child’s

Pose” by Călin Peter Netzer—the 2013 Golden Bear winner. Added to this

impressively auspicious pedigree, the picture’s subject-matter—the “Green

Card soldier” phenomenon, by which aspiring Americans can fast-track their US

citizenship via military service—strikes topical chords in an year when

right-wing presidential candidates have adopted predictably belligerent stances

on complex immigration issues.

The Republicans’ attention-seeker-in-chief Donald Trump set the hawkish tone

back in June 2015, in the very speech that announced his candidacy: “I

would build a great wall,” he thundered, “and nobody builds walls

better than me, believe me, and I’ll build them very inexpensively. I will

build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay

for that wall.” Ambition is one thing, of course; achievement quite

another. And while “Soy Nero” may yet pick up some kind of prize here—from a jury headed by the politically-engaged American actress Meryl Streep—Pitts’ breathtaking frontier pyrotechnics turn out to be a false dawn in more

ways than one.

Early, largely wordless sequences set around the Tijuana border—whose fences

extend out into the Pacific Ocean, and form ad-hoc volleyball nets for

international “teams”—make an impact. But screenplay issues kick in

almost as soon as Nero has made it to California, quickly obtaining a ride from

a genial-seeming veteran, Seymour (Michael Harney). “I’m a DREAM

kid,” he enthuses, detailing his plan to obtain the magical Green Card via

the “DREAM Act” which he says came into force in the aftermath of 9/11. Seymour,

a nicely ambiguous figure who comes across like a chummy uncle one minute and a

potentially murderous reactionary the next, is scathing about Nero’s goals.

Showing him a plain filled with wind turbines—which, he reckons, consume more

energy than they create—Seymour explains that the green-card soldier program

is, like much else in the United States, a “set-up” built on cruel

deception.

Nero does seem to have been somewhat misinformed about the DREAM Act

(Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors)—which has so far

failed to pass into legislation despite seven separate senatorial attempts. Not

that you’d grasp this from the film, which is very fuzzy about how the business

of Green Card soldiers actually operates. Pitts and Razulescu reportedly drew

particular inspiration from the case of former USMC combatant Daniel Torres—credited as an advisor on the film—who was deported despite having served a

tour of duty in Iraq. Theirs is a fictionalized take on the experience of people

like Torres—end titles inform that the film is “dedicated to all the

Green Card soldiers who were deported after having served” in the US

military—and it’s one that rings slightly but naggingly false at nearly every

turn.

The picture’s pacing unhelpfully slackens off once Nero meets up with his

half-brother Jesus (Ian Casselberry), whose name he idiosyncratically

pronounces “Jee-zus” rather than the usual Latino

“Hay-soos”, and who seems to have struck it very rich indeed in this

golden land of opportunity. As Nero hangs out in Jesus’ palatial Beverly Hills

mansion, the lap of luxury he’s enjoying is obviously far too good to be true,

far too good to last. The explanation, when it finally arrives, involves a

louche rock-star who’s only glimpsed for a few seconds in deep shadow—but who

looks very much like Jack White (thanked in the credits)—and makes little

retrospective sense.

Soon after, Nero

somehow uses Jesus’ fake ID to get into the military—details of this are

blithely skipped over via ellipsis—and the rest of the running-time takes

place in an unspecified middle-eastern location where Nero/Jesus mans a

checkpoint with a pair of African-American comrades. The film again grinds to a

halt as these two soldiers, who are referred to only via their home-towns of “Compton” (Darrell Britt-Gibson) and “Bronx” (Aml Ameen), heatedly discuss

pop-culture matters—there’s a definite improv air here, and one suspects that

the screenplay here merely says something like “[they argue over rap.]”

“Bronx” later reacts with unlikely incredulity and insult when he meets a

fellow platoon-member whose name happens to be Mohammed (“he’s a f**kin’

A-rab!”); Compton gets his time in the spotlight when he’s impressed by

the music coming out of a family’s car and launches into an impromptu dance

routine. Several painful minutes seem to elapse before the performance is

mercifully ended by Compton’s commanding officer McCloud.

The latter is played by Pitt’s fellow “Argo” alumnus Rory Cochrane,

who gets all of 20 minutes on screen and roughly half a line of dialogue, but

inexplicably nabs second billing—in both the opening and closing credits—ahead of individuals like Harney and Casselberry who perform much heavier

lifting. Could Pitts be making some oblique, meta-textual point about the lack

of meritocracy in the United States in general and in the film industry in

particular? Perhaps, but it’s more likely that McCloud was the victim of some

very late-in-the-day rewrites.

Even so, too much of “Soy Nero” the first

produced screenplay from both Pitts or Razulescu to be mainly written in

English still feels like a first-draft effort, and there’s little in Pitts’

directorial box of tricks to distract us from the script’s nagging

deficiencies. The “slow cinema” tropes he deployed in his Iranian

outings are once again trotted out, to enervating effect in a final act notable

for its lack of suspense and tension—even during a bomb-disposal sequence

whose protracted nature leaves us in zero doubt about the explosive outcome. The victim, Armstrong (Kyle Davis), is on screen too briefly to really register

as a character—so his death can’t help but leave us unmoved. It’s a different

matter with Nero himself, of course, as the eponymous post-teen is present in

pretty much every scene. But despite the efforts of the likeable Ortiz, this

lad just never feels like an organic, three-dimensional creation. He makes most

impact in the first few minutes when he’s interrogated by hostile border

officials, and his features exude a sullenly guarded restraint—the subtlety

of Ortiz’s work undercut by the fact that Nero (“black” in Italian)

sports a black-and-white t-shirt bearing the large logo “Enemy.”

The central idea of military service as a route to citizenship was, meanwhile,

dealt with more illuminatingly and imaginatively twenty years ago in Paul

Verhoeven’s scaldingly satirical “Starship Troopers.” But whereas slow, worthily downbeat

treatments of serious issues such as “Soy Nero” will generally be

extended the benefit of the doubt—and berths in prestigious festival

competitions—when it comes to interplanetary science-fiction extravaganzas, the

attitude in too many snobby quarters is still a case of

“Argo-f**k-yourself.”