“What have I got if I haven’t got those awards? I’ve got nothing; I’ve got the building and the staff that’s in it. And an unmade picture.” –Richard Williams, in “Richard Williams: The Thief Who Never Gave Up”

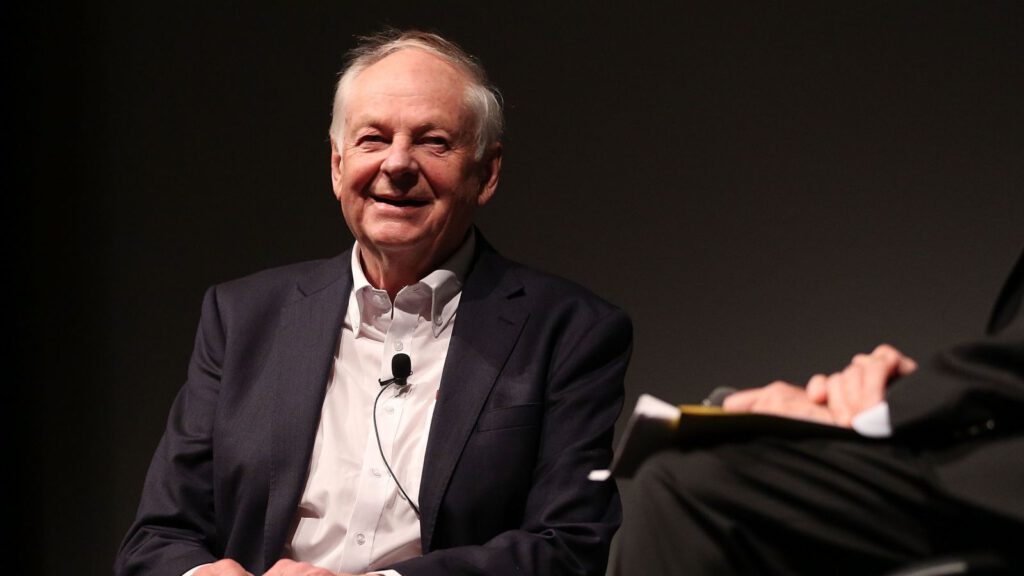

A photo of Canadian-British animator and three-time Oscar-winner Richard Williams might perfectly illustrate the term “scenius,” a neologism coined by music pioneer Brian Eno that repositions art as the product of multiple (and not singular) related creative geniuses: “Scenius stands for the intelligence and the intuition of a whole cultural scene. It is the communal form of the concept of the genius.”

Williams has often been hailed for the “persistence of vision” (also the title of a 2012 documentary about Williams) that he needed to continue working, for decades, on “The Thief and the Cobbler,” a gorgeous animated fairy tale (based on Persian and Ottoman paintings and fables by Sufi folk hero Nasreddin Hodja) that was sadly never completed. But Williams, who died of cancer this weekend, was also significantly aided in his quest to make animation “grow up” by old-school cartoonists like Art Babbitt (an influential former Disney animator who got on the studio’s shit list after he joined the animators’ strike of 1941); Emery Hawkins (who re-designed Woody Woodpecker in the mid-1940s); and Grim Natwick (Fleischer Studios animator most famous for his work on Betty Boop).

Williams had previously learned from and worked with most of these artists (all dead) on projects like his BAFTA-winning 1971 TV version of “A Christmas Carol” (executive produced by “Loonie Tunes” God Chuck Jones, who recommended Williams for the job); the 1977 feature “Raggedy Ann & Andy: A Musical”; and the Oscar-winning 1988 live-action/animated hybrid “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” Williams’ career and work is not, in that sense, the result of solitary ingenuity, but of collective imagination.

Born in 1933, Williams first saw and was taken in by “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves” when he was five years old; that film’s Evil Queen antagonist was animated by Babbitt, his future colleague. At 16, Williams had a personal epiphany after looking at a series of Rembrandt paintings: “I suddenly understood what all this art stuff was all about” he recalls in a 1982 made-for-TV documentary called “Richard Williams: The Thief Who Never Gave Up.” For Williams, there wasn’t a huge difference between what Rembrandt did with oil paintings and what cartoonists could do with cel animation: “if you were Rembrandt today, you wouldn’t be able to resist animation.”

Williams was a renowned perfectionist: his formative use of perspective was matched by his meticulous attention to detail and general preference for animating “on the twos” (ie: 12 frames per second) or even “on the ones” (24 frames per second); most of Williams’s peers cut corners (and frames) by animating on the threes, four, or fives. Williams, working on “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” was also a pioneer in his use of multi-layered image-compositing (now mostly done digitally), as realized by Industrial Light and Magic (for more on that process, check out Cartoon Brew’s interview with Ed Jones, the supervisor of optical photography for “Roger Rabbit”).

Williams was also a pragmatist: he became an award-winning commercial artist in order to finance “The Thief and the Cobbler,” a project that he started developing in 1968. Richard Williams Animation, Williams’s London animation studio, would go on to win hundreds of awards after making thousands of animated advertisements, many of which can be seen on the expansive TheThiefArchive YouTube channel (as well as the animated sequences he produced for several live-action films’ opening credits, including “Return of the Pink Panther” and “Casino Royale”). Williams hated the modern “art world” (“I couldn’t stand the idea of doing paintings for rich industrialists’ wives”), but was convinced, after a 1963 conversation with British filmmaker Clive Donner, that he should apply as much sincerity and ingenuity as he could to his commercial work. You can also see Williams commiserating with his animators in “The Thief Who Never Gave Up,” when he recommends that they not spread themselves too thin: “If [the clients] won’t give us the time, you have to drop the quality [of your work]. You just drop it. And drop it again.”

Williams obviously did not take his own advice during the 24-plus-years-long production of “The Thief and the Cobbler,” which was seized from him in 1992 by Warner Brothers and a completion bond company, who would later re-sell the film’s raw materials to Miramax, who eventually released a drastically simplified version of the film under the title of “Arabian Knight.” That year, Williams also had to lay off a couple dozen of his own animators and shut down Richard Williams Animation.

The Miramax cut was praised by Jake Eberts, who represented Allied Films, a British production company that invested $10 million in “The Thief and the Cobbler.” According to Eberts, Williams “could never finish a scene,” citing how much attention he paid to the unnamed Thief, a character who, like Tack the Cobbler, was mute (Williams often likened them to Charlie Chaplin and Laurel and Hardy). Alexander Williams, Richard’s son and a contributing animator on “The Thief and the Cobbler,” argued that Miramax’s changes were drastic and untrue to his father’s vision, highlighting the unnecessary dialogue they gave to some characters whose mouths didn’t noticeably move (Incidentally: Richard Williams was, for a while, reluctant to speak about the Miramax cut). Still: Eberts, in a 1995 interview with The Austin American-Statesman’s Robert Welkos, maintains that Miramax “made extremely good changes.”

To be fair, “The Thief and the Cobbler” was the most extravagant project that Williams undertook. It was also, in many ways, the culmination of his training and imagination: the film’s first ten minutes of footage took 14 years to complete and cost about 1.5 million British pounds to produce (adjusting for inflation, that’s about $31 million today). In 1982, Williams estimated that he needed 10 million more pounds to complete his project. But several well-documented obstacles prevented Williams from achieving his goal, as film critic Bilge Ebiri recalls in an essential piece for Drugstore Culture:

“In 1978, a Saudi Arabian Prince expressed interest in helping bankroll the production, but backed away after Williams ran wildly over-budget and behind schedule completing a ten-minute sequence to show prospective partners. In the mid-1980s, ‘Star Wars’ producer Gary Kurtz became involved, and Williams met Steven Spielberg and Robert Zemeckis, who were looking for an animator to help them with Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”

Zemeckis and Spielberg’s project inarguably revitalized Williams’s passion project, but “The Thief and the Cobbler” is also a continuation of Williams’ earlier short films. You can see Williams’s characteristic preoccupation with the divided self—the greedy, galvanizing Thief is just as essential to the story’s action as the kind-hearted, but inept Cobbler—in earlier shorts like “Love Me, Love Me, Love Me,” an anti-“moral tale” from 1962 that concludes with a shaggy dog punchline: “When it comes to love, no one really has it good, especially stuffed alligators named Charlie.”

You can also see the thematic and stylistic seeds that would fully blossom in the “The Thief and the Cobbler” in Williams’ “The Little Island,” an Oscar-winning 1958 short about three men who each carry one thought in their respective heads: truth, beauty, and goodness. That cartoon establishes a perennial Williams concern: humanity’s irreconcilable spiritual imbalance, represented by his three main characters’ absurd, intractable, and borderline fascistic devotion to their ideals. That theme recurs in “A Lecture on Man,” a 1962 animated collage that combines hand-drawn animation and found photographs—a recurring feature in Williams’ commercial work—that illustrate man’s incomplete nature since, in the short, men either lack the heart or the brains to care for themselves.

You can also see Williams’s fingerprints all over the animated sequences from “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” a feature that Williams initially found difficult to conceive. Still, Williams signed onto the project after extensive discussions with director Robert Zemeckis and a 45-second animation test of Roger Rabbit falling down a flight of stairs. Williams’ use of fluid camera-work to film the cel animation—a process that created a lot of extra work for Williams’ animators—was the key to his creative success, not to mention a five-step process of image-compositing that led Williams and his team to say the film was made in “two-and-a-half-D.” The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Steven Rea, in a 1988 article, smartly broke down Williams and his team’s process as follows:

(1) a story-board sketch of the scene; (2) the live-action shoot (with puppeteers and technicians manipulating props that would ultimately be ‘held’ by the Toons); (3) a rough line drawing done on a photostat blowup of the live-action frame; (4) a hand-painted cel drawing, which was then shot on its own frame; (5) a cel that was then added to the live-action frame, with elements of light and shadow to render the animation three-dimensional.

Williams’s fastidious approach was essential to the success of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” one of the top-grossing films in 1988 and a major catalyst for the decade-long Disney Renaissance that began in 1989. That same year: 560 lots of animation cels from “Who Framed Roger Rabbit”—ranging in initial cost from $400-20,000—were sold at auction at Sotheby’s; the sales of these cels helped to finance new buildings and infrastructure at Disney’s Burbank studio, including two domes shaped like Mickey Mouse’s ears.

Ironically, Disney’s resurgence indirectly killed “The Thief and the Cobbler”: the concurrent production of “Aladdin” led Warner Brothers to pull their support from Williams’s project, leaving its completion to a bond company that, in 1992, seized Williams’s film. California-based animator Fred Calvert was then given the thankless job of completing the film and, while Calvert ultimately gave the job to a group of Korean animators, he was reluctant to be involved in any capacity. In 1995, Calvert told Welkos that “I really didn’t want to do it[…]but if I didn’t do it, it would have been given off to the lowest bidder. I took it as a way to try and preserve something and at least get the thing on the screen and let it be seen.” Calvert’s cut (which took an extra 18 months to complete) was a musical in the vein of recent Disney hits like “The Little Mermaid” and “Beauty and the Beast.”

The most complete director-approved version of “The Thief and the Cobbler” is the “A Moment in Time” edit that premiered in 2013 and preserved by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (in “The Art Babbitt Collection”). You can also find a copy of this edit in Disney’s “Animation Research Library.” There’s also a riveting fan edit of the film, called the “Recobbled” cut, that was completed by Williams expert Garrett Gilchrist. Gilchrist’s version can be found on YouTube; it’s the most comprehensive edit of the film to date.

Watching Gilchrist’s version of “The Thief and the Cobbler” after Williams’s death is an overwhelming experience. So much care was put into this film and so much invisible work that nobody but Williams, his fellow animators, or peers will fully appreciate. Still, it’s hard not to wonder what Williams would have done had he been able to complete scenes like the one where the Thief walks an impossibly high tight-rope.

“The Thief and the Cobbler” is the apex of Williams’ career and as close as he came to making animation grow up. Its “Duck Amuck”-style conclusion—the Thief grabs hold of the film surrounding him, pockets it, and skulks off into the far distance—is also a bittersweet, but fittingly abrupt high note for Williams’s career to end on. Some stories don’t have a happy ending: they’re just adopted and refashioned by other imperfect geniuses.