Fallen

empires influence the regions of their past dominion long after their collapse.

In South Africa, a land that had been torn apart over centuries between

conflicts with the Dutch and the British that left behind an

insidious culture of white supremacy, the stains of the past are still present,

though not as pronounced as a wrecked Star Destroyer on the landscape of Jakku.

As J.J. Abrams’ “Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens” looks to the past to define the

future of the legendary space opera, I was curious to see how the film would be

greeted in a land divided over time by war and mandated segregation. What I

encountered in two showings in different cities was a wildly different reaction

to the movie itself, though the post-film reactions—particularly to the new

characters—were practically uniform. As we still feel today in America, or as

can be seen in “The Force Awakens,” change, be it racial or political, is a

painfully slow process, sometimes feeling futile in its gradual pacing.

In Pretoria,

a city that is approximately 50% white, there’s a general sense of

non-state-sanctioned segregation. Restaurants and malls are mostly populated by

an affluent white clientele, while the service workers are overwhelmingly

black. At a Sunday afternoon showing of “The Force Awakens” at an upscale

shopping mall with its own Mercedes-Benz showroom, I caught the first of my two

South African screenings of Abrams’ much-anticipated film.

The 3D

screening with the mostly white audience was defined by the stoicism of its

viewers. Moments that were greeted with rousing cheers from American audiences

were given no reaction at all. Even the numerous moments of levity in the film

were barely greeted with a chuckle, if at all. Matters weren’t helped by the

astoundingly dim projection, which was made worse by the naturally dimming 3D

effect. Even worse, the auditorium’s subwoofer was blown, crackling and

rattling during many of Kylo Ren’s most menacing moments. As I would find out

just a few days later, the theater chain where I saw the film, Ster-Kinekor,

doesn’t have the highest standards when it comes to presentation, despite being

the most prevalent movie theater chain in South Africa.

Upon leaving

the auditorium in Pretoria, each person I talked with said they grew up with

the films and had an affection for the series shepherded by George Lucas. Aside

from the young child who enthusiastically proclaimed upon exiting the theater,

“That was cool, man!” the general reaction was rather tempered. “It wasn’t life

changing or anything,” said Denzel, a young black man, outside the theater.

When I asked which of the new characters stuck out to him, his reply was

simple: “The black guy,” in reference to John Boyega’s Finn.

I then asked

a trio of white teens what they thought of the film. Like Denzel, the teens

were tempered in their enthusiasm towards the film. The big question on their

mind was the lineage of Daisy Ridley’s Rey. “We’re all wondering who’s the

girl,” said one of the teens wearing a Nirvana t-shirt.

One aspect

of “The Force Awakens” that has drawn its fair share of criticism in the

United States took on a new meaning for me in South Africa: the lack of change

since the fall of the Empire in “Return of the Jedi.” Though by no means

do I believe that J.J. Abrams and company intended their space fantasy to have

its own well-defined set of politics, its greater deficiencies took on a new

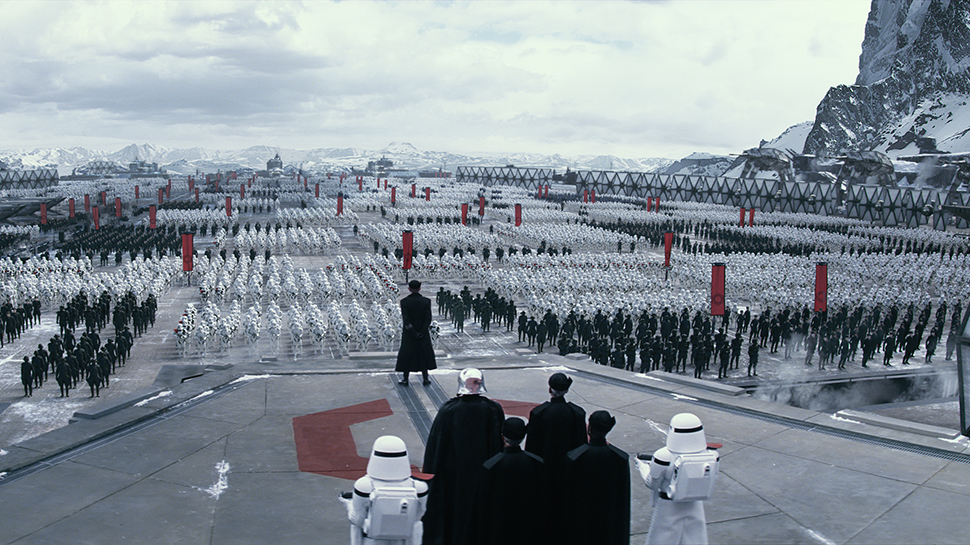

significance in the surroundings of Pretoria. The First Order just picks up the

mantle of the Empire following its collapse at the end of “Return of the Jedi,”

as if over the course of 30 years the New Republic had gone through all those

troubles to establish itself, only to leave its constituents disillusioned. Again,

I’m likely putting more thought into this than the creators of the film did.

But when viewed in the land where Nelson Mandela fought and won against an

oppressive regime and which is currently in a state of disillusionment with the

wildly unpopular President Jacob Zuma, whose recent shuffle of Finance

Ministers has left the South African currency devalued, the Abrams reboot of

the Empire has a ring of truth to it. It’s as if lacking a transcendent figure

of Mandela or Luke Skywalker leads to an apathy and disillusionment that leads

to the resurgence of the past status quo. President Zuma has fostered a culture

of political corruption, including allowing the escape of Sudanese President

Omar al-Bashir, a wanted war criminal, from facing extradition to the

International Criminal Court, which combined with severe economic woes could

lead to a combustible political climate ripe for extremism on all fronts.

Although details are scarce of how exactly the Republic falls apart enough for

a new rebellion to take place, it’s safe to assume that similar problems in

leadership must have taken place for someone like Han Solo to regress back to

smuggling and piracy.

Conversely,

the feeling around Johannesburg was markedly different. Though it should be

stated that I was at another relatively upscale mall and the service workers

were predominantly black, the general ratio of customers was much more

representative of the city’s overall demographics, which skews closer to around

80% non-white. In the Sandton City Mall the film was once again plagued with

projection issues. Early scenes of the film were presented in the wrong aspect

ratio of 1.85:1 before slowly adjusting to the 2.35:1 that was intended. Once

again, the projection was woefully dim. The inadequacies of Ster-Kinekor’s

projection left me with a newfound appreciation for the often pristine

presentation experienced at common press screenings. When coupled with the

issues affecting screenings of “The Hateful Eight” stateside, the need for

projectionists in a digital age came racing to my mind.

That

particular audience in Johannesburg had none of the stoicism that was

overwhelming with the Pretoria audience. The more rousing moments of action and

comedy garnered more specific responses, with BB-8 and Finn constantly earning

more laughter and cheers than the entire film in Pretoria. Outside the

auditorium the reaction from audience members who spoke to me was much more

enthusiastic as well. “It was interesting. It was well done, the way they

continued the series,” said Dave, a thirtysomething white man. “It was all very

true to the nature of the movies,” he continued. Victor, a black man around the

same age as his friend Dave, was fond of one particular new character: “I like

Finn.” Though once again I was presented with a racial divide over the new set

of characters, there was a sense of racial harmony over the breakthrough star

of “The Force Awakens”—BB-8. Everyone loves that little droid.

Having now

seen “The Force Awakens” three times, I’ve gotten a clearer sense of its

strengths and weaknesses. Among its strengths, the film constantly propels

forward at a blistering pace that doesn’t make its structural flaws too evident

in the moment. But there’s a crucial mistake hidden in the film, a

socio-political aspect of its internal world that dilutes the film’s story of

good and evil. While Kylo Ren embodies a sense of entitlement and lust for

power that was present yet never effective within Anakin Skywalker in the

prequels—emphasized by his saying “I can have anything I want,” or declaring

the lightsaber held by a black man to be his birthright—the true failing of

“The Force Awakens” is having its Stormtroopers be merely the product of

off-screen brainwashing. It places the power structure of evil as nothing more

than a top-down affair, with the army that perpetuates atrocities fully clear

of responsibility for their actions. Even the Nazis, which are an obvious

influence on the Empire and First Order in design and scheme, didn’t merely

brainwash their members: they gave them a belief that they were Übermenschen,

that they were superior to all. The same could be said of the British or the

Boers that perpetrated apartheid. Yet it wasn’t merely four or five powerful

figures and a whole lot of brainwashing, but a system that provided an

advantage to a select few and giving them cause to defend an unjust state.

While the prequels and “The Force Awakens” have portrayed the Stormtrooper as

soldier existing solely through cloning and brainwashing, at least the original

films were comfortable in retaining ambiguity about the evil nature of the men

behind the white masks.

Like

everywhere else in the world, “The Force Awakens” was the number one movie in

South Africa, scoring the second highest opening of the year behind only

“Furious 7,” which remains the highest grossing movie of the year in the

country. But it’s not entirely surprising that “Furious 7” would outrace “The

Force Awakens” in this region. Cinema can reflect real life conflicts in

fantastical locations or provide us with absurd escapism. In a country that has

lived in the shadow of an empire for centuries, whose oppressive regime came to

an end 11 years following “Return of the Jedi,” tales of power struggles

between light and darkness might reflect reality too closely to be the grand

escapist fun that we see it in America, no matter how long ago in a galaxy far,

far away they’re supposed to take place. As we’re constantly reminded of here

in America, it’s painful and uncomfortable to look at the horrors of the past,

even through the lens of fiction and fantasy.