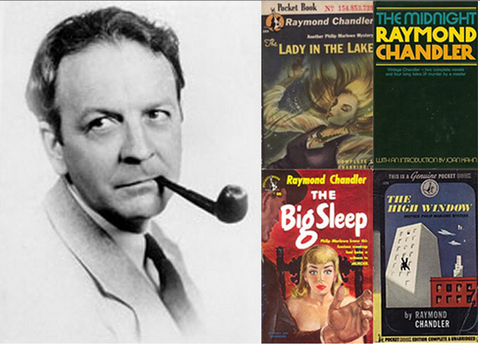

My Far-Flung Correspondent Anath White in Los Angeles writes me: “Raymond Chandler wrote this wonderful piece for the Atlantic Monthly in March of 1948.”

Oscar Night in Hollywood,

by Raymond Chandler

I

Five or six years ago a distinguished writer-director (if I may be permitted

the epithet in connection with a Hollywood personage) was co-author of a

screen play nominated for an Academy Award. He was too nervous to attend the proceedings on the big night, so he was listening to a broadcast at home,

pacing the floor tensely, chewing his fingers, taking long breaths, scowling

and debating with himself in hoarse whispers whether to stick it out until

the Oscars were announced, or turn the damned radio off and read about it in

the papers the next morning.

Getting a little tired of all this artistic temperament in the home, his

wife suddenly came up with one of those awful remarks which achieve a wry

immortality in Hollywood: “For Pete’s sake, don’t take it so seriously,

darling. After all, Luise Rainer won it twice.”

To those who did not see the famous telephone scene in “The Great Ziegfeld,” or any of the subsequent versions of it which Miss Rainer played in other pictures, with and without telephone, this remark will lack punch. To others it will serve as well as anything to express that cynical despair with which Hollywood people regard their own highest distinction. It isn’t so much that the awards never go to fine achievements as that those fine achievements are not rewarded as such. They are rewarded as fine achievements in box-office hits. You can’t be an All-American on a losing team.

Technically, they are voted, but actually they are not decided by the use of

whatever artistic and critical wisdom Hollywood may happen to possess. They are ballyhooed, pushed, yelled, screamed, and in every way propagandized into the consciousness of the voters so incessantly, in the weeks before the final balloting, that everything except the golden aura of the box office is forgotten.

The Motion Picture Academy, at considerable expense and with great

efficiency, runs all the nominated pictures at its own theater, showing each

picture twice, once in the afternoon, once in the evening. A nominated

picture is one in connection with which any kind of work is nominated for an

award, not necessarily acting, directing, or writing; it may be a purely

technical matter such as set-dressing or sound work. This running of

pictures has the object of permitting the voters to look at films which they

may happen to have missed or to have partly forgotten. It is an attempt to

make them realize that pictures released early in the year, and since

overlaid with several thicknesses of battered celluloid, are still in the

running and that consideration of only those released a short time before

the end of the year is not quite just.

The effort is largely a waste. The people with votes don’t go to these

showings. They send their relatives, friends, or servants. They have had

enough of looking at pictures, and the voices of destiny are by no means

inaudible in the Hollywood air. They have a brassy tone, but they are more

than distinct.

All this is good democracy of a sort. We elect Congressmen and Presidents in much the same way, so why not actors, cameramen, writers, and all rest of

the people who have to do with the making of pictures? If we permit noise,

ballyhoo, and theater to influence us in the selection of the people who are

to run the country, why should we object to the same methods in the

selection of meritorious achievements in the film business? If we can

huckster a President into the White House, why cannot we huckster the

agonized Miss Joan Crawford or the hard and beautiful Miss Olivia de

Havilland into possession of one of those golden statuettes which express

the motion picture industry’s frantic desire to kiss itself on the back of

its neck?

The only answer I can think of is that the motion picture is an art. I say

this with a very small voice. It is an inconsiderable statement and has a

hard time not sounding a little ludicrous. Nevertheless it is a fact, not in

the least diminished by the further facts that its ethos is so far pretty

low and that its techniques are dominated by some pretty awful people.

If you think most motion pictures are bad, which they are (including the

foreign), find out from some initiate how they are made, and you will be

astonished that any of them could be good. Making a fine motion picture is

like painting “The Laughing Cavalier” in Macy’s basement, with a floorwalker

to mix your colors for you. Of course most motion pictures are bad. Why

wouldn’t they be? Apart from its own intrinsic handicaps of excessive cost,

hypercritical bluenosed censorship, and the lack of any single-minded

controlling force in the making, the motion picture is bad because 90 per

cent of its source material is tripe, and the other 10 per cent is a little

too virile and plain-spoken for the putty-minded clerics, the elderly

ingénues of the women’s clubs, and the tender guardians of that godawful

mixture of boredom and bad manners known more eloquently as the

Impressionable Age.

The point is not whether there are bad motion pictures or even whether the

average motion picture is bad, but whether the motion picture is an artistic

medium of sufficient dignity and accomplishment to be treated with respect

by the people who control its destinies. Those who deride the motion picture

usually are satisfied that they have thrown the book at it by declaring it

to be a form of mass entertainment.

As if that meant anything. Greek drama, which is still considered quite

respectable by most intellectuals, was mass entertainment to the Athenian

freeman. So, within its economic and topographical limits, was the

Elizabethan drama. The great cathedrals of Europe, although not exactly

built to while away an afternoon, certainly had an aesthetic and spiritual

effect on the ordinary man. Today, if not always, the fugues and chorales of

Bach, the symphonies of Mozart, Borodin, and Brahms, the violin concertos of Vivaldi, the piano sonatas of Scarlatti, and a great deal of what was once

rather recondite music are mass entertainment by virtue of radio. Not all

fools love it, but not all fools love anything more literate than a comic

strip. It might reasonably be said that all art at some time and in some

manner becomes mass entertainment, and that if it does not it dies and is

forgotten.

The motion picture admittedly is faced with too large a mass; it must please

too many people and offend too few, the second of these restrictions being

infinitely more damaging to it artistically than the first. The people who

sneer at the motion picture as an art form are furthermore seldom willing to

consider it at its best. They insist upon judging it by the picture they saw

last week or yesterday; which is even more absurd (in view of the sheer

quantity of production) than to judge literature by last week’s

best-sellers, or the dramatic art by even the best of the current Broadway

hits. In a novel you can still say what you like, and the stage is free

almost to the point of obscenity, but the motion picture made in Hollywood,

if it is to create art at all, must do so within such strangling limitations

of subject and treatment that it is a blind wonder it ever achieves any

distinction beyond the purely mechanical slickness of a glass and chromium

bathroom. If it were merely a transplanted literary or dramatic art, it

certainly would not. The hucksters and the bluenoses would between them see to that.

But the motion picture is not a transplanted literary or dramatic art, any

more than it is a plastic art. It has elements of all these, but in its

essential structure it is much closer to music, in the sense that its finest

effects can be independent of precise meaning, that its transitions can be

more eloquent than its high-lit scenes, and that its dissolves and camera

movements, which cannot be censored, are often far more emotionally

effective than its plots, which can.

Not only is the motion picture an art, but it is the one entirely new art

that has been evolved on this planet for hundreds of years. It is the only

art at which we of this generation have any possible chance to greatly

excel. In painting, music, and architecture we are not even second-rate by

comparison with the best work of the past. In sculpture we are just funny.

In prose literature we not only lack style but we lack the educational and

historical background to know what style is. Our fiction and drama are

adept, empty, often intriguing, and so mechanical that in another fifty

years at most they will be produced by machines with rows of push buttons.

We have no popular poetry in the grand style, merely delicate or witty or

bitter or obscure verses. Our novels are transient propaganda when they are

what is called “significant,” and bedtime reading when they are not.

But in the motion picture we possess an art medium whose glories are not all

behind us. It has already produced great work, and if, comparatively and

proportionately, far too little of that great work has been achieved in

Hollywood, I think that is all the more reason why in its annual tribal

dance of the stars and the big-shot producers Hollywood should contrive a

little quiet awareness of the fact. Of course it won’t. I’m just

daydreaming.

II

How business has always been a little overnoisy, overdressed, overbrash.

Actors are threatened people. Before films came along to make them rich they often had need of a desperate gaiety. Some of these qualities prolonged

beyond a strict necessity have passed into the Hollywood mores anproduced

that very exhausting thing, the Hollywood manner, which is a chronic case of

spurious excitement over absolutely nothing.

Nevertheless, and for once in a lifetime, I have to admit that Academy

Awards night is a good show and quite funny in spots, although I’ll admire

you if you can laugh at all of it. If you can go past those awful idiot

faces on the bleachers outside the theater without a sense of the collapse

of the human intelligence; if you can stand the hailstorm of flash bulbs

popping at the poor patient actors who, like kings and queens, have never

the right to look bored; if you can glance out over this gathered assemblage

of what is supposed to be the elite of Hollywood and say to yourself without

a sinking feeling, “In these hands lie the destinies of the only original

art the modern world has conceived”; if you can laugh, and you probably

will, at the cast-off jokes from the comedians on the stage, stuff that

wasn’t good enough to use on their radio shows; if you can stand the fake

sentimentality and the platitudes of the officials and the mincing elocution

of the glamour queens (you ought to hear them with four martinis down the

hatch); if you can do all these things with grace and pleasure, and not have

a wild and forsaken horror at the thought that most of these people actually

take this shoddy performance seriously; and if you can then go out into the

night to see half the police force of Los Angeles gathered to protect the

golden ones from the mob in the free seats but not from that awful moaning

sound they give out, like destiny whistling through a hollow shell; if you

can do all these things and still feel next morning that the picture

business is worth the attention of one single intelligent, artistic mind,

then in the picture business you certainly belong, because this sort of

vulgarity is part of its inevitable price.

Glancing over the program of the Awards before the show starts, one is apt

to forget that this is really an actors’, directors’, and big-shot

producers’ rodeo. It is for the people who make pictures (they think), not

just for the people who work on them. But these gaudy characters are a

kindly bunch at heart; they know that a lot of small-fry characters in minor

technical jobs, such as cameramen, musicians, cutters, writers, soundmen,

and the inventors of new equipment, have to be given something to amuse them and make them feel mildly elated. So the performance was formerly divided into two parts, with an intermission. On the occasion I attended, however, one of the Masters of Ceremony (I forget which–there was a steady stream of them, like bus passengers) announced that there would be no intermission this year and that they would proceed immediately to the important part of the program. Let me repeat, the important part of the program.

Perverse fellow that I am, I found myself intrigued by the unimportant part

of the program also. I found my sympathies engaged by the lesser ingredients of picture-making, some of which have been enumerated above. I was intrigue by the efficiently quick on-and-off that was given to these minnows of the picture business; by their nervous attempts via the microphone to give most of the credit for their work to some stuffed shirt in a corner office; by the fact that technical developments which may mean many millions of dollars to the industry, and may on occasion influence the whole procedure of picture-making, are just not worth explaining to the audience at all; by the casual, cavalier treatment given to film-editing and to camera work, two of the essential arts of film-making, almost and sometimes quite equal to direction, and much more important than all but the very best acting;

intrigued most of all perhaps by the formal tribute which is invariably made

to the importance of the writer, without whom, my dear, dear friends,

nothing could be done at all, but who is for all that merely the climax of

the unimportant part of the program.

III

I am also intrigued by the voting. It was formerly done by all the members of all the various guilds, including the extras and bit players. Then it was realized that this gave too much voting power to rather unimportant groups, so the voting on various classes of awards was restricted to the guilds which were presumed to have some critical intelligence on the subject.

Evidently this did not work either, and the next change was to have the

nominating done by the specialist guilds, and the voting only by members of

the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

It doesn’t really seem to make much difference how the voting is done. The

quality of the work is still only recognized in the context of success. A

superb job in a flop picture would get you nothing, a routine job in a

winner will be voted in. It is against this background of success-worship

that the voting is done, with the incidental music supplied by a stream of

advertising in the trade papers (which even intelligent people read in

Hollywood) designed to put all other pictures than those advertised out of

your head at balloting time.

The psychological effect is very great on minds conditioned to thinking of

merit solely in terms of box office and ballyhoo. The members of the Academy live in this atmosphere, and they are enormously suggestible people, as are all workers in Hollywood. If they are contracted to studios, they are made to feel that it is a matter of group patriotism to vote for the products of their own lot. They are informally advised not to waste their votes, not to plump for something that can’t win, especially something made on another lot.

I do not feel any profound conviction, for example, as to whether “The Best

Years of Our Lives” was even the best Hollywood motion picture of 1946. It

depends on what you mean by best. It had a first-class director, some fine

actors, and the most appealing sympathy gag in years. It probably had as

much all-around distinction as Hollywood is presently capable of. That it

had the kind of class and simple art possessed by Open City or the stalwart

and magnificent impact of Henry V only an idiot would claim. In a sense it

did not have art at all. It had that kind of sentimentality which is almost

but not quite humanity, and that kind of adeptness which is almost but not

quite style. And it had them in large doses, which always helps.

The governing board of the Academy is at great pains to protect the honesty

and the secrecy of the voting. It is done by anonymous numbered ballots, and

the ballots are sent, not to any agency of the motion picture industry, but

to a well-known firm of public accountants. The results, in sealed

envelopes, are borne by an emissary of the firm right onto the stage of the

theater where the Awards be made, and there for the first time, one at a

time, they are made known. Surely precaution would go no further. No one

could possibly have known in advance any of these results, not even in

Hollywood where every agent learns the closely guarded secrets of the

studios with no apparent trouble. If there are secrets in Hollywood, which I

sometimes doubt, this voting ought to be one of them.

IV

As for a deeper kind of honesty, I think it is about time for the Academy of

Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to use a little of it up by declaring in a

forthright manner that foreign pictures are outside competition and will

remain so until they face the same economic situation and the same

strangling censorship that Hollywood faces. It is all very well to say how

clever and artistic the French are, how true to life, what subtle actors

they have, what an honest sense of the earth, what forthrightness in dealing

the bawdy side of life. The French can afford these things, we cannot. To

the Italians they are permitted, to us they are denied. Even the English

possess a freedom we lack. How much did Brief Encounter cost? It would have cost at least a million and a half in Hollywood; in order to get that money

back, and the distribution costs on top of the negative costs, it would have

had to contain innumerable crowd-pleasing ingredients, the very lack of

which is what makes it a good picture.

Since the Academy is not an international tribunal of film art it should

stop pretending to be one. If foreign pictures have no practical chance

whatsoever of winning a major award they should not be nominated. At the

very beginning of the performance in 1947 a special Oscar was awarded to

Laurence Olivier for “Henry V,”, although it was among those nominated as best picture of the year. There could be no more obvious way of saying it was not going to win. A couple of minor technical awards and a couple of minor writing awards were also given to foreign pictures, but nothing that ran

into important coin, just side meat. Whether these awards were deserved is

beside the point, which is that they were minor awards and were intended to

be minor awards, and that there was no possibility whatsoever of any

foreign-made picture winning a major award.

To outsiders it might appear that something devious went on here. To those

who know Hollywood, all that went on was the secure knowledge and awareness that the Oscars exist for and by Hollywood, their purpose is to maintain the supremacy of Hollywood, their standards and problems are the standards and problems of Hollywood, and their phoniness is the phoniness of Hollywood. But the Academy cannot, without appearing ridiculous, maintain a pose of internationalism by tossing a few minor baubles to the foreigners while carefully keeping all the top-drawer jewelry for itself. As a writer I resent that writing awards should be among these baubles, and as a member of the Motion Picture Academy I resent its trying to put itself in a position which its annual performance before the public shows it quite unfit to occupy.

If the actors and actresses like the silly show, and I’m not sure at all the

best of them do, they at least know how to look elegant in a strong light,

and how to make with the wide-eyed and oh, so humble little speeches as if

they believed them. If the big producers like it, and I’m quite sure they do

because it contains the only ingredients they really understand–promotion

values and the additional grosses that go with them–the producers at least

know what they are fighting for. But if the quiet, earnest, and slightly

cynical people who really make motion pictures like it, and I’m quite sure

they don’t, well, after all, it comes only once a year, and it’s no worse

than a lot of the sleazy vaudeville they have to push out of the way to get

their work done.

Of course that’s not quite the point either. The head of a large studio once

said privately that in his candid opinion the motion picture business was 25

per cent honest business and the other 75 per cent pure conniving. He didn’t say anything about art, although he may have heard of it.

But that is the real point, isn’t it?–whether these annual Awards,

regardless of the grotesque ritual which accompanies them, really represent

anything at all of artistic importance to the motion picture medium,

anything clear and honest that remains after the lights are dimmed, the

minks are put away, and the aspirin is swallowed? I don’t think they do. I

think they are just theater and not even good theater. As for the personal

prestige that goes with winning an Oscar, it may with luck last long enough

for your agent to get your contract rewritten and your price jacked up

another notch. But over the years and in the hearts of men of good will? I

hardly think so.

Once upon a time a once very successful Hollywood lady decided (or was

forced) to sell her lovely furnishings at auction, together with her lovely

home. On the day before she moved out she was showing a party of her friends through the house for a private view. One of them noticed that the lady was using her two golden Oscars as doorstops. It seemed they were just about the right weight, and she had sort of forgotten they were gold.