One of Roger Ebert’s favorite filmmakers, Ingmar Bergman, will receive an essential collector’s edition box set from the Criterion Collection in honor of his 100th birthday. “Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema,” scheduled for release on November 20th, spans six decades and 39 films, all of which will be restored on pristine Blu-rays. Accompanied by a 248-page book of essays, as well as by more than thirty hours of supplemental features, this set is structured like a film festival, presenting Bergman’s extraordinary body of work as a multi-part screening series.

Serving as the opening night selection of the box set in 1955’s “Smiles of a Summer Night,” a film that “acted as an artistic and professional turning point” for the filmmaker, according to Ebert. In his Great Movies essay, Ebert detailed how the Swedish Film Institute took a gamble by spending $100,000 on the film (the largest ever for a Swedish movie up till that time), and it paid off spectacularly, becoming an international success and preventing the director from ever having to “scramble for financing” again in his career. The film also showcased Bergman’s under-appreciated sense of humor.

“We are meant to understand that everyone’s sensibilities are erotically alert because it is one of those endless northern days where night is but a finger dragging the dusk between one day and the next,” wrote Ebert. “What happens during the course of the long night involves smiles and a great deal more, including a providential bed that slides through a wall from one bedroom to the next. […] There is an abundance of passion here, but none of it reckless; the characters consider the moral weight of their actions, and while not reluctant to misbehave, feel a need to explain, if only to themselves. Perhaps here, in an uncharacteristic comedy, Bergman is expressing the same need.” Accompanying this film in this first section of the box set are 1946’s “Crisis,” 1947’s “A Ship to India,” 1950’s “To Joy,” 1951’s “Summer Interlude,” 1953’s “Summer with Monika,” 1954’s “A Lesson in Love,” 1955’s “Dreams” and 1957’s famous “Wild Strawberries.”

Headlining the Centerpiece One section of the box set are the television and theatrical versions of 1974’s “Scenes from a Marriage,” a masterwork that Ebert dubbed, “one of the truest, most luminous love stories ever made.” In his four-star review, Roger wrote, “The marriage of Johan and Marianne will disintegrate soon after the film begins, but their love will not. They will fight and curse each other, and it will be a wicked divorce, but in some fundamental way they have touched, really touched, and the memory of that touching will be something to hold to all of their days. […] Beyond love, beyond marriage, beyond the selfishness that destroys love, beyond the centrifugal force that sends egos whirling away from each other and prevents enduring relationships–beyond all these things, there still remains what we know of each other, that we care about each other, that in twenty years these people have touched and known so deeply that they still remember, and still need.”

Included along with it is Bergman’s final film, 2005’s “Saraband,” revisiting the same couple decades later. “The movie is not about the resolution of this plot,” wrote Ebert in his four-star review. “It is about the way people persist in creating misery by placing the demands of their egos above the need for happiness — their own happiness, and that of those around them. […] The overwhelming fact about this movie is its awareness of time. Thirty-two years have passed since ‘Scenes from a Marriage.’ The years have passed for Bergman, for Ullmann, for Josephson, and for us. Whatever else he is telling us in ‘Saraband,’ Bergman is telling is that life will end on the terms with which we have lived it. If we are bitter now, we will not be victorious later; we will still be bitter. Here is a movie about people who have lived so long, hell has not been able to wait for them.”

Two films from 1968 are also featured here, “Hour of the Wolf” and “Shame.” Ebert awarded “Wolf” three stars, writing, “Much of the film retains Bergman’s ability to obtain deeply emotional results with very stark, almost objective, scenes. […] If we allow the images to slip past the gates of logic and enter the deeper levels of our mind, and if we accept Bergman’s horror story instead of questioning it, [the film] works magnificently.” “Shame” earned four stars from the critic, who observed that the film might’ve had a greater impact if Bergman had made it “specifically about Vietnam, but I believe he was unhappy that ‘Persona’ had been decoded by critics as being against that war, all because of one image; it was about, and against, a great deal more. In this film you can see him shifting away from message and toward the close regard of human behavior and personality (as in his ‘Silence of God’ trilogy). That did not turn him into a realist or a conventional storyteller, but it freed him from ideology.”

The complete “Silence of God” trilogy is also here, beginning with 1961’s “Through a Glass Darkly.” “You can freeze almost any frame of this film and be looking at a striking still photograph,” wrote Ebert in his Great Movies essay. “Nothing is done casually. Verticals are employed to partition characters into a limited part of the screen. Diagonals indicate discord. The characters move into and out of view around the cottage as if in a play. The visual orchestration underlines the disturbance of Karin’s mental illness, and the no smaller turmoil within the minds of the others.”

That film was followed by 1962’s “Winter Light,” which Roger praised as yet another triumph for Bergman’s frequent cinematographer, Sven Nykvist. “The film’s visual style is one of rigorous simplicity,” wrote Roger in his Great Movies essay. “Nykvist does not use a single camera movement for effect. He only wants to regard, to show. His compositions, while sometimes dramatic, are mostly static. He uses slow push-ins and pull-outs to underline dialogue of intensity. His gaze is so unblinking that sequences with the potential to be boring, like the opening scenes of the consecration and distribution of hosts and wine, become fascinating: More is going on here than ritual, and there are buried currents between the communicants. Nykvist focuses above all on faces, in closeup and medium shot, and they are even the real subject of longer shots, recalling Bergman’s belief that the human face is the most fascinating study for the cinema.”

Rounding out the trilogy is 1963’s “The Silence,” a film that broke taboos upon its initial release. “The juxtaposition of the child with the scenes of adult behavior is disquieting, although we note that Bergman used the usual strategy for separating the boy into separate shots so he would not see and hear what we do,” wrote Ebert in his Great Movies Essay. “The film itself was scandalous at the time, with nudity and unusual sexual frankness. Bergman is somehow always thought of as cerebral and detached, but shocking carnality is often a part of his work; one thing he more rarely offers, however, is a sincere and tender romantic scene.” Also included in the Centerpiece One section are 1960’s shattering masterpiece, “The Virgin Spring,” 1969’s “The Passion of Anna,” 1970’s “Fårö Document,” 1979’s “Fårö Document 1979” and 1980’s “From the Life of the Marionettes.”

Centerpiece Two, the third section in the box set, begins with perhaps Bergman’s most infamous picture, 1957’s “The Seventh Seal,” containing Max Von Sydow’s famous chess game on the beach with the Grim Reaper. “Long considered one of the masterpieces of cinema, it is now a little embarrassing to some viewers, with its stark imagery and its uncompromising subject, which is no less than the absence of God,” wrote Ebert in his Great Movies essay. “Films are no longer concerned with the silence of God but with the chattering of men. We are uneasy to find Bergman asking existential questions in an age of irony, and Bergman himself, starting with ‘Persona,’ found more subtle ways to ask the same questions. But the directness of ‘The Seventh Seal’ is its strength: This is an uncompromising film, regarding good and evil with the same simplicity and faith as its hero.”

1975’s “The Magic Flute,” a family-friendly opera, was a charming departure for Bergman, and received four stars from Ebert. “Bergman lets us see how the special effects work, he gives us backstage glimpses of the players hurrying to meet cues and relaxing during the intermission, and we’re reminded of the many other backstage scenes in his films,” wrote the critic. “We’re supposed to be conscious of watching a performance, and yet at some level Bergman also wants Mozart’s fantasy to work as a story, a preposterous tale, and it does. This must be the most delightful film ever made from an opera.”

Two other films in this section, however, also found Bergman outside his comfort zone and received rare negative reviews from Ebert, beginning with 1971’s “The Touch.” In his two-and-a-half star review, Ebert wrote that the film was “not only a disappointment but an unexpected failure of tone from a director to whom tone has usually been second nature. This is his first feature in English, but I don’t think language is the problem. Instead, I think it has something to do with the way Bergman has conceived his characters and chooses to reveal them to us. We make unexpected discoveries about them rather late in the film, and suddenly, so that what began as an intense study of character ends up on the edge of melodrama.” 1977’s “The Serpent’s Egg,” filmed in Berlin, fared even worse with Ebert, earning only one-and-a-half stars. “Maybe the point is that Bergman is best as a filmmaker on his native ground, no matter how unhappy he may feel there,” wrote the critic. “The movie is a cry of pain and protest, a loud and jarring assault, but it is not a statement and it is certainly not a whole and organic work of art.”

Yet Bergman was back on track, according to Ebert, with 1984’s “After the Rehearsal.” “After seeing it, I thought I understood the film entirely,” confessed Ebert in his four-star review. “Now I am not so sure. Like so many of Bergman’s films, and especially the spare ‘chamber films’ it joins ( ‘Winter Light,’ ‘Persona’), it consists of unadorned surfaces concealing fathomless depths. […]It is actually more of a sacramental confession, as if Bergman, the son of a Lutheran bishop, now sees the stage as his confessional and is asking the audience to bless and forgive him. (His gravest sin, as I read the film, is not lust or adultery, but the sin of taking advantage of others — of manipulating them with his power and intellect.)” Completing the Centerpiece Two section is 1953’s “Sawdust and Tinsel,” 1958’s “The Magician,” 1960’s “The Devil’s Eye,” 1964’s “All These Women” and 1969’s “The Rite.”

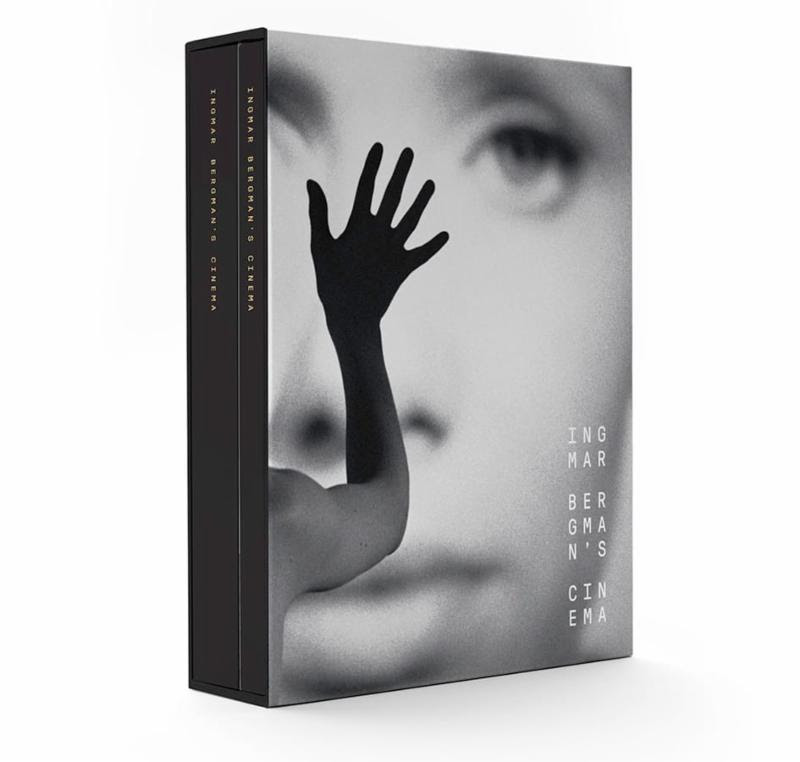

Centerpiece Three is where viewers can find the aforementioned “Persona,” the 1966 landmark featuring iconic imagery chosen for the packaging of the box set. In his Great Movies essay, Ebert wrote that “Persona” is “a film we return to over the years, for the beauty of its images and because we hope to understand its mysteries. It is apparently not a difficult film: Everything that happens is perfectly clear, and even the dream sequences are clear–as dreams. But it suggests buried truths, and we despair of finding them. ‘Persona’ was one of the first movies I reviewed, in 1967. I did not think I understood it. A third of a century later I know most of what I am ever likely to know about films, and I think I understand that the best approach to ‘Persona’ is a literal one. It is exactly about what it seems to be about.”

Equally unforgettable is 1972’s “Cries and Whispers” a film that Ebert, in his Great Movies essay, loved, even as it proved difficult to watch. “‘Cries and Whispers’ envelops us in a tomb of dread, pain and hate, and to counter these powerful feelings it summons selfless love,” wrote Ebert. “It is, I think, Ingmar Bergman’s way of treating his own self-disgust, and his envy of those who have faith. […] Bergman never made another film this painful. To see it is to touch the extremes of human feeling. It is so personal, so penetrating of privacy, we almost want to look away.” 1948’s “Port of Call,” 1949’s “Thirst,” 1952’s “Waiting Women,” 1958’s “Brink of Life” and 1978’s “Autumn Sonata” are also included in this section.

Last but not least, the closing night selection of “Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema” is 1982’s “Fanny and Alexander,” available in both its theatrical and television versions. The picture, Ebert noted in his Great Movies essay, was intended to be Bergman’s “last film, and in it, he tends to the business of being young, of being middle-aged, of being old, of being a man, woman, Christian, Jew, sane, crazy, rich, poor, religious, profane. He creates a world in which the utmost certainty exists side by side with ghosts and magic, and a gallery of characters who are unforgettable in their peculiarities. Small wonder one of his inspirations was Dickens. […] Bergman somehow glides beyond the mere telling of his story into a kind of hypnotic series of events that have the clarity and fascination of dreams. Rarely have I felt so strongly during a movie that my mind had been shifted into a different kind of reality. […] The movie is astonishingly beautiful. To see the film in a theater is the way to first come to it, because the colors and shadows are so rich and the sounds so enveloping. At the end, I was subdued and yet exhilarated; something had happened to me that was outside language, that was spiritual, that incorporated Bergman’s mysticism; one of his characters suggests that our lives flow into each other’s, that even a pebble is an idea of God, that there is a level just out of view where everything really happens.”

Since this month marks the 100th year centennial of Bergman’s birth on July 14th, the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck is offering a variety of programming, including a new entry in the original series Creative Marriages on the filmmaker’s intimate collaboration with actor Liv Ullmann, and a series of Friday-night double features that pair some of Bergman’s most influential works with the films they’ve inspired.