On the heels of false rumors that Idris Elba was next in line to inherit James Bond’s license to kill, arguments for the inclusive casting of the character and against a non-white actor playing Bond have landed like thunderballs. This makes sense. For going on 60 years, audiences have only ever seen Bond as white. Now it finally appears that, per director Antoine Fuqua, producer Barbara Broccoli has concurred that “it’s time” for a non-white Bond. A non-white Bond appears an easy choice in 2018, when a culture once dominated by straight white men has started making room for once-marginalized voices. Casting a Bond of color would indeed change the franchise.

And if you look at how Bond and the franchise have evolved over the last two decades, you’ll see that this wouldn’t be an arbitrary change, but an evolutionary one. You could even say that it’s what the Bond series has been building towards, as it strove to infuse stories with political details drawn from recent headlines while making Bond seem like even more of an outsider than he did already.

We should begin by enthusiastically stating that, in the character’s earliest incarnations—on the page as well as in the first few decades of films—it made a world of sense for Bond to be white. Although reflexive resistance to casting Elba, or any non-white performer, tends to be rooted in racism, it’s not accurate to say that it doesn’t matter whether Bond is white. Bond’s race is indeed a part of the character, and a key bit of context necessary for understanding how he functions. As opposed to Bond’s race being a neutral character—or Bond’s actions not being motivated by race, as Matt Miller asserts—it seems fairer to say that Bond’s whiteness was inevitable, considering the era and culture that birthed him.

Bond debuted in Casino Royale, published in 1954 by former British Naval Officer Ian Fleming. Fleming’s politics were written into the books: rather than appearing as apolitical, Bond explicitly works for Her Majesty’s Secret Service, and is born out of Cold War paranoia. His enemies and allies often are associated with the respective international relationships that the United Kingdom had with such countries as the United States, Russia (formerly the USSR), China, Japan and Germany. First played onscreen by Sean Connery in 1962’s “Dr. No,” Bond is not just an action hero with good taste in cars and shoes. He is an arm of state politics and an emblem of midcentury British imperialism.

Once you realize that Bond’s actions are never apolitical, you start to understand how deliberate the political subtext (or super text) in these films can be.

International tensions and cultural stereotypes and resentments are all over the series from the start. They grow harder to ignore in later films. And they’re largely shaped by the point-of-view of the Hollywood-adjacent British film industry which, like the British government, is run by white men, and has been slow to cede ground to other points-of-view.

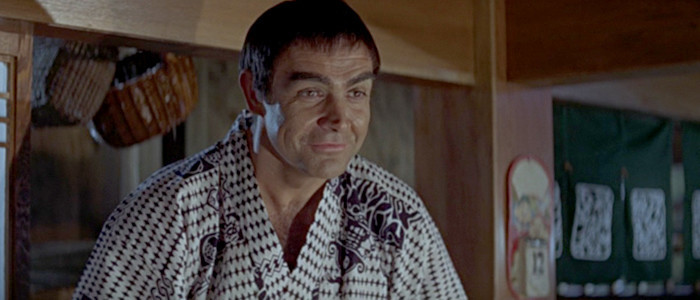

Bond appears in yellowface for nearly a third of the running time of “You Only Live Twice,” and the tense relationship the UK and Japan is discussed in dialogue. When Bond strolls into a hotel room sopping wet in “Die Another Day,” the Chinese manager declares decisively, “Hong Kong is our turf now, Bond,” just before he goes to face the film’s bad guy, a North Korean dictator’s son who has had cosmetic and DNA surgery to become white. In “From Russia with Love,” Bond … well, you get the picture. The appeal to the Bond movies implicitly is its geopolitics, even when we’re simply reading it as “Bond fights the Russians,” and even then, Bond represents certain ideas. (SPECTRE, the recurring terrorist organization that Bond battles against across multiple titles, is fascinating because they are bound not only by ideology, but by the awareness of fraught international relationships: see “You Only Live Twice.”)

But Broccoli is right to say its time for a different kind of Bond. Every entry in the series has, to varying degrees, had to justify the necessity of existing, but that urge became more overt as the distance between Bond and the Cold War turned into a chasm. The Pierce Brosnan films, which kicked off with 1995’s “GoldenEye,” were already referencing the Cold War in faintly nostalgic terms, as a conflict that was at least more clearly defined than the chaos the character had to deal with after the USSR broke apart. The context of Bond had to change again for 2006’s reboot/origin story “Casino Royale.” The shadow of September 11th and the international War on Terror hung over the character, who was now angsty, angry, gritty, and world-weary. Daniel Craig became an emblem of post-9/11 trauma and frustration, even ambivalence.

The Craig films (consisting of “Casino Royale,” “Quantum of Solace,” Skyfall,” and “Spectre”) do what the rest of the franchise don’t: they constantly interrogate Bond’s relevance to the world. Craig’s version of Bond is shaped by the brokenness of the society and politics around him. His struggle to “become Bond” in a definite, easily communicable way, as Sean Connery or Roger Moore did so easily, is indicative of how stunted and fractured the world has become. He’s worse at his job (he barely succeeds at missions anymore), and his relationship with his license to kill has soured. His masculinity is starting to bend. Maybe he’s starting to realize the world doesn’t need him anymore.

In “Spectre,” Bond returns to the exotic locales the movies were once iconic for, and encounters little else but rubble and ruin: the result of British Imperialism and colonialism. The film begins somewhat pretentious (in a delightful way): “The dead are alive,” it tells us. Does that makes 007 the ghost of the British Empire? What does Bond even mean in the 21st century? We already know he’s a relic of the Cold War—and as M [Judi Dench] calls him in “GoldenEye,” “a sexist, misogynist dinosaur”—and he knows it. So now what?

Such questions are central to the Craig films. The answer so far has been implicitly suggest that Bond doesn’t need to exist in a world where warfare and espionage are no longer on-the-ground affairs—a curious example of a wildly popular franchise arguing against itself.

All of which brings us to the first reason that a non-white Bond would be not just fresh, but sensible and necessary: casting Bond as non-white would make the franchise’s politics a lot more sophisticated and challenging, without contradicting anything that it has shown us in the past.

The Bond franchise has, over the course of its run, turned increasingly inwards; in its last decade or so, it’s been hard to argue that Craig’s cycle of films demonstrated unwavering support of the British government and its implicit heroism, crimes, and misdemeanors. “Quantum of Solace” showed us that Bond, often a stand-in for British imperial powers, could rampage. “Skyfall” and “Spectre'”s pair of Shakespearean monologues from M (Dench) and Blofeld (Christoph Waltz) confirmed that if the Empire hasn’t already fallen, the series is critical of its nihilistic need to keep going no matter what.

A non-white Bond would push international audiences to realize that the world view and behavior represented in Bond films aren’t just a white thing. White people are no longer sole arbiters of colonialist attitudes or actions, on the ground or otherwise.

In that sense, a non-white actor playing Bond would not so much be a subversion of Bond’s politics, but an admittance that those politics are bound to statehood and institution, not always just to race.

However, it would not be sufficient to cast an actor of color as Bond and not change anything else about the movies.

A non-white Bond would not be a one-dimensional representational win if the franchise continued to make only minor tweaks. Another white Bond wouldn’t demand that we reconsider the politics of the whole franchise. Any other race or ethnicity would compel it.

Imagine an Asian Bond after having witnessed the character’s (and Britain’s) relationship with Asian countries in such films as “You Only Live Twice,” “Man with the Golden Gun,” “Tomorrow Never Dies” and “Die Another Day.” A black Bond would make us to think about Britain’s slave territories, represented onscreen in “Live and Let Die,” essentially a blaxploitation movie with a black villain and a white hero. What thoughts would be inspired by an Indian Bond, considering the colonial history so glancingly referenced in “Octopussy”?

More to the point, Bond is, in effect, a very handsome supercop. “You are just a stupid policeman,” Dr. No derisively says to him. He has, as Gladys Knight is wont to sing, a license to kill. And while he’s more inclined to work with other government agencies, local and state police are technically his allies. “As lawless as his actions may appear to be, underneath it all Bond really believes in Goodness and Order and Freedom and Democracy and, yes, even Law. Scratch the tuxedo and and you’ll find a police uniform,” writes scholar Greg Forster.

Considering white-dominated police forces’ typically unstable relationship with nonwhites, a black Bond would complicate our racialized understanding of Bond and law rather drastically. As recent films like “Crime + Punishment” are exploring the complicated racial dynamics at play for black police officers, it would be irresponsible for the Bond series to not confront a nonwhite Bond’s feelings about being a part of an institution that routinely exercises force against people who look like him.

None of this should be daunting to the people who hold the keys to the Bond franchise. They should see this moment as an opportunity, in between car chases, gunfights and seductions, to explore new dramatic as well as political territory, and even tackle questions of race and institutional power.

That institution is England.

Bond is so representative of Great Britain and all that she stands for that the series’ self-awareness began to mushroom as early as 1973, when Roger Moore slipped into Bond’s shoes in “Live and Let Die.” Only a couple films later, he would he ski jump off a mountain and reveal that his parachute was the Union Jack in “The Spy Who Loved Me” (1977). That was a statement, joking yet serious, that Bond was the UK.

Politically, the history of the UK is a history of whiteness.

What would it feel like to drop someone like Elba or “Attack the Block”‘s John Boyega into Bond’s suit in, say, “The Living Daylights,” which takes place in Afghanistan? Could he make jokes about sex and England, about other national cuisines or customs like in “Octopussy”? Would that feel natural, or would there be something off and unusual about shoehorning in a black Bond without somehow addressing those racial implications?

And what about “GoldenEye,” and the line “For England, James?” Alec Trevelyan (Sean Bean) asks that question of Bond, bookending the film, wondering if they still believe in what they’re doing. The answer is different both times. At the end, Bond is allowed to be a little skeptical. Could Boyega be skeptical of England’s ultimate goal, the implication that their version of goodness and lawfulness should be the standard for the rest of the developed world? Would we laugh at the very idea of a black Bond agreeing with the sentiments of a character like Alec Trevelyan? In “Casino Royale,” M remarks to Bond, “Any thug can kill.” Could an actor like Daniel Kaluuya shrug off that kind of casual designation of the hierarchy of killing? Or would the moment be more pointed, barbed? Could Idris Elba unquestioningly wear a Union Jack that’s shot out of one of his gadgets, or would doubt begin to inform his character?

Whiteness is also what allowed Bond to come and go from the institution that employs him. Bond has left MI6 or has gone rogue a number of times over the decades, only to be welcomed back. Only someone who was white who could be part of a white dominated institution, doubt it, leave it, and return without much fuss.

Of all the iterations of the Bond franchise, it’s Craig’s films that pave the way for a non-white bond. They have a different understanding of Bond altogether, beyond a broad “grittiness.” Daniel Craig’s Bond is alienated.

Jokes can be made about the one dimensionality of Bond’s character throughout most of the series, but “GoldenEye” nodded to unlocking his psychology and how he felt about the destruction he’s left in his wake. Trevelyan sneers, “I might as well ask you for the vodka martinis that have silenced the screams of all the men you’ve killed … or if you find forgiveness in the arms of all those willing women, for all the dead ones you failed to protect.” The Craig Bond films go further, suggesting that you have to be a bit dead inside in the first place to work for an organization like Bond’s employer. In “Casino Royale,” Vesper Lynd (Eva Green) asks, “You can switch off so easily, can’t you? It doesn’t bother you? Killing those people?” Bond retorts, “Well, I wouldn’t be very good at my job if it did.” There is unsureness on his face after he says this. Through Craig, we understand how Bond became a shell.

If the Craig films are implicitly arguing that Bond has not, as we have assumed, been able to assimilate into the role of a Double-O agent, working for Her Majesty’s Secret Service, what if that extended into a metaphor about how people of color struggle with assimilation on a broader level?

A non-white Bond could be portrayed as someone who’s wearing a white mask in order to survive. That’s an intriguing and potentially powerful step beyond the already considerable alienation that Craig brought to the part.

The most wonderful thing about the Bond franchise is its malleability. The films morph to fit within whatever genre or style is popular at the moment. Bond has been played by many actors. And he has become increasingly intricate as a character.

It would be a level up for Bond to confront what it actually means to be Other, not just alienated or ambivalent.

A non-white Bond could articulate a struggle to assimilate into a broader national or governmental politic, and better establish the push and pull of the character’s own agency, and his often unknowing role as a pawn. The unsureness that Bond already exudes, via Craig, would be grounded in psychological and concrete reality. Subtext would become text, but in an electrifying way. A nonwhite actor would make a lot of things official, and turn Bond into something besides a spectre of the past.