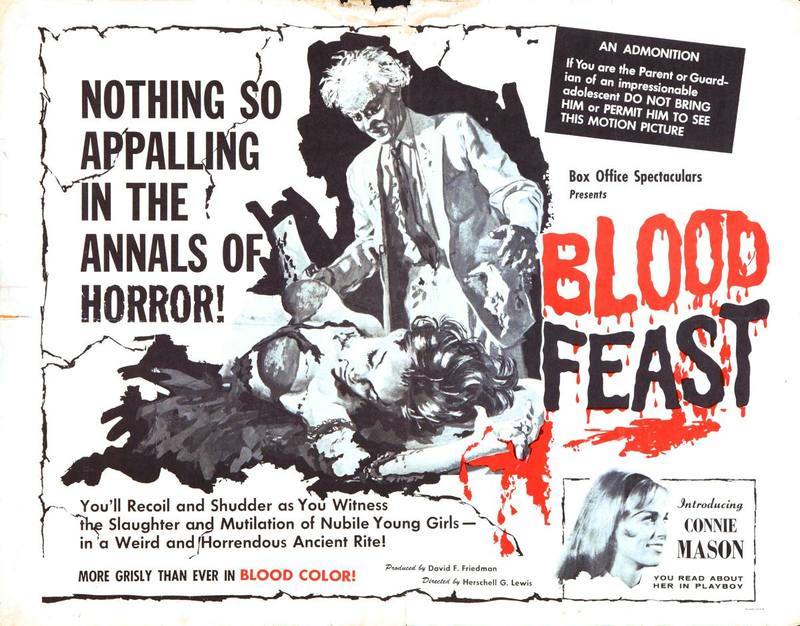

The late Herschell Gordon Lewis, the self-proclaimed “Godfather of Gore,” was not the first filmmaker to exploit violence for commercial means; if you leaf through the Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, you’ll see a few other gory entertainments listed before Lewis’ infamous 1963 feature “Blood Feast” arrived on cinema screens, including “Jigouku” (1960), a surreal Japanese vision of Hell, and “Poor White Trash” (1957), a crude hicksploitation picture. But Lewis and his business partner David Friedman might have been the first to perfect the formula for selling films that showcased gore for gore’s sake, a dubious but incredibly durable triumph. Where Alfred Hitchcock sold suspense and “shock” in his campaign for “Psycho” and kept onscreen blood to a minimum (and painted it black, courtesy of black-and-white film, which abstracted the nastiness), Lewis and Friedman sold blood, blood and more blood, in glorious color. “Blood Feast” may have been influenced by everything from Tod Browning’s “Dracula” to the Parisian Grand Guignol theater, but it was an amateurish movie, and Lewis knew it. He later told the AV Club, “We put together an outrageous campaign … the first of its kind. The basis of that campaign was ‘nothing so appalling in the annals of film,’ and we had blood dripping out of the poster.” To paraphrase Kroger Babb, Friedman’s exploitation mentor, Lewis and Friedman sold “the sizzle, not the steak.”

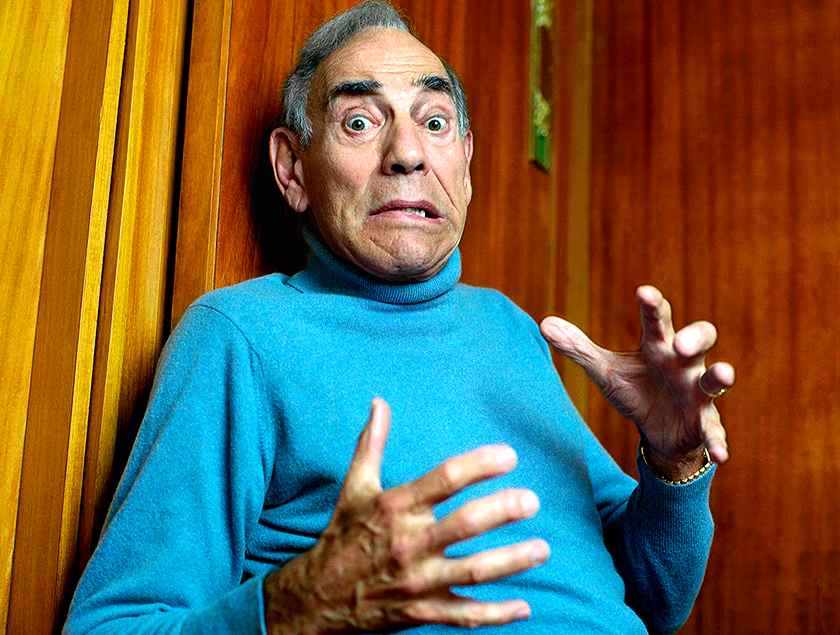

Lewis was not an active filmmaker when he passed away at the age of 87. In fact, he retired from making movies in 1972, though he briefly returned to making films in 2002, when he directed a sequel to his breakthrough feature, “Blood Feast 2: All U Can Eat.” Lewis was, by this point, a rich man. He lived with his wife Margo in Florida after enjoying a long and lucrative career as a public speaker, promoting the benefits of direct market advertising (ie: junk mail). He could have returned to filmmaking if he wanted to, but if the project wasn’t already set up for him, he wasn’t really interested. In fact, Lewis would be the first person to tell you that filmmaking was not a form of artistic expression for him. Movies, for Herschell, were primarily a means of making money, then a personal source of grief, and finally, perhaps, a means of personal gratification. When one of the authors of this piece visited him in his home in 2012, he had no significant memorabilia. Filmmaking was, at this point, a past life, one that he would only revisit if an interviewer paid him. The interviewer paid him. With a cashier’s check, of course. Because there was only one Herschell Gordon Lewis.

Still, before Lewis and Friedman, nobody sought to make a film whose main source of spectacle was gore, and none profited from it the way the makers of “Blood Feast” did. Lewis and Friedman are historically significant for this reason, and not just to gore-hounds fascinated by scenes of evisceration, exploding heads and the like. The bloodiness of “Blood Feast” would go on to influence such filmmakers as Frank Hennenlotter, who dedicated “Basket Case” (1982) to Lewis; Tom Savini, who recalls Lewis’s work as “very visceral, very different from anything else I’d ever seen, and it always stuck in my head;” and John Carpenter, who commends Lewis for, “[wanting] to slap us in the face, and say ‘Look at this stuff.” John Waters prominently featured a “Blood Feast” poster in his violent satire “Serial Mom” and interviewed Lewis alongside Russ Meyer in his book Shock Value: A Tasteful Book About Bad Taste. Stuart Gordon has said that he referred back to “Blood Feast” when devising practical effects for “Re-Animator,” a movie whose main setting is a morgue where autopsies and Frankenstein-like medical experiments are performed.

But even as subsequent generations of filmmakers paid him homage, Lewis never deluded himself into thinking that “Blood Feast” was a triumph of artistry rather than sheer gall plus marketing acumen. When the writers of Cahiers du Cinema praised Lewis’s “Blood Feast” and “Two Thousand Maniacs” (1964) as two of the best horror films of all time and classified Lewis as a “subject for further study.” Lewis joked, “That’s what they say about cancer.”

Lewis was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in June 1929. After working as an English professor at Mississippi State College and then a disc jockey at an AM radio station in Racine, Wisconsin, he moved to Chicago in the mid-to-late ’50s to work at Alexander and Associates, a Chicago advertising firm. When Lewis realized that his employer was suffering from mismanagement, he bought a controlling half-interest in Alexander and Associates and renamed the company Lewis and Martin Films (after himself and fairweather business partner Martin Schmidhofer) and relocated the company to California. But Schmidhofer soon ditched Lewis after he joined the Cameraman’s Union, and moved to Florida. Lewis moved back to Chicago after bitterly concluding that “the only way to make money in this business is to shoot features.”

Lewis’s career as an exploitation filmmaker took off when he partnered with Friedman. The two met when Friedman, an ex-publicist at Paramount Pictures, was working at the Chicago-based Modern Film Distributors. The two sized each other up:

“What kind of films do you want to make?” Friedman asked, semi-seriously.

“The kind that make money,” said Lewis.

Lewis and Friedman both wanted to be their own bosses. They earned intrigued notices in trade publications like BoxOffice Magazine and Variety with two relatively tame (i.e.: boring) youth pictures: “The Prime Time” (1959) and “Living Venus” (1961). They then made a couple of sun-bathing/nudist colony pictures and some “nudie cuties,” softer-than-softcore sex films that were essentially burlesque-style slapstick comedies about voyeurs who ogled women in states of undress. Some of these films, released under pseudonyms, made money, but not enough for the trouble they gave Lewis and Friedman. It didn’t matter that films like “Nature’s Playmates” (1962) and “The Adventure or Lucky Pierre” (1961) weren’t good; what really sunk them was that the market was flooded with amateurish skin flicks. Lewis and Friedman realized they couldn’t get a solid foothold in the field, so they devised a list of topics that they could sell on a budget—stuff that fellow exploitation filmmakers hadn’t thought of dealing with in films, and that the major studios couldn’t or wouldn’t touch. Friedman’s contributions to the list included “Nazi torture camp,” and “goona-goona,” the latter referring to titillating pseudo-ethnographic “shockumentaries” like “Latuko” (1952) “Karamoja” (1955), and “Mau Mau” (also 1955). Lewis’s second biggest contribution to the list was an edict: “No more nudies.”

With that goal in mind, the two men settled on “gore” (Lewis’ suggestion) as their genre of choice. They drove down to Florida, where they’d shot a couple of their previous sexploitation projects and filmed “Blood Feast.” The plot was relatively simple, albeit odd: a peculiar Miami Beach caterer (the indelible Mal Arnold) murders hapless nubiles and prepares their organs and limbs as a tribute to the Egyptian goddess Ishtar. The police, led by Bill Kerwin’s baffled detective, are stumped. And Arnold, despite his goofy pasted-on eyebrows, proves to be a prolific vandal of flesh.

Lewis tended to be cagey about the film’s budget. He refused to discuss dollars and cents during an interview near the end of his life. The best estimate we’ve come across is $24,500. But whatever the exact price tag, this was not a shoestring-budgeted indie; it was a pair of old sneakers with holes in the soles, laced with knotted twine. Lewis and Friedman budgeted for a seven day production but ended up banging the whole thing out in five. Even Roger Corman, a producer of legendary speed and efficiency, would’ve considered that a tight shoot.

The film premiered at Peoria’s Bel Air, a drive-in theater. Beforehand, Lewis fretted that audiences wouldn’t be scared of his make-up effects, a combination of offal, gelatin, kaopectate and fake blood from Barfred’s pharmacy. “Thankfully, people in the theater did not share my reaction,” Lewis joked during our interview. The feast of blood that is “Blood Feast” may not seem sophisticated by 21st century torture porn standards. But it got a rise out of early audiences, particularly the scene where Arnold’s character pulls the tongue out of Olsen’s head—actually a sheep’s tongue.

In the film, Olsen gags, and crosses her eyes as her character’s tongue is yanked out. The sheep’s tongue that Arnold laboriously pulled from his co-star’s mouth was rotting and had to be sprayed with Pine-Sol to prevent Olsen from throwing up. So when Olsen greets Arnold’s advances with horror and disgust, she’s not acting, she’s reacting. Lewis later suggested that Olsen was only cast in “Blood Feast” because she looked as if she could fit a second tongue in her mouth. He was not, to put it mildly, an actor’s director.

But this film wasn’t an actors’ showcase; it was a bucket of guts, a work that would later be considered the first “splatter” picture. When Olsen’s tongue disappeared during the Peoria premiere, the crowd swallowed theirs. “Here are all these fellows sitting on their fenders, yelling and laughing and screaming,” Lewis remembered. “‘Hey, wotta lousy movie!’ Then comes the tongue scene, and suddenly everything goes dead quiet. And all you can see are these white eyeballs staring up at the screen. That one brought ‘em up short!” The tongue scene made Lewis’ career as decisively as the ear scene in “Reservoir Dogs” made Quentin Tarantino’s. Lewis had invented a new genre—or at least a new way of packaging a specialized niche within an existing genre, horror.

Arnold’s performance personifies the gross, broadly macabre, punch-drunk tone of “Blood Feast.” Lewis imitated the Theater du Grand Guignol’s signature “douche écossaise” style, which film historian David Skal defines as, “a ‘Scotch’ shower of alternating emotional temperatures.” Lewis’ attempts at quickly shifting tones was less than successful, a failing that some have attributed to the film’s 100-yard-dash of a shooting schedule, but that was more likely due to Lewis’ inconsistent work ethic, a flaw that dogged him throughout his career. He was a wizard at the P.T. Barnum aspects of his profession, but no great shakes at actually directing movies.

His inconsistent work ethic is most apparent in Arnold’s performance. The actor had worked in community theaters and had even taken acting lessons—more than most of Lewis’s cast. But you can’t tell that Arnold was an experienced thespian based on his performance in “Blood Feast.” Arnold was asked to google his eyes and stick his chin out whenever he spoke. Because Lewis had Todd Browning’s “Dracula” on the brain, he asked Arnold to talk in a “Transylvanian” accent that Friedman once described as “the worst Bela Lugosi voice anyone ever heard.” He also asked Arnold to affect a limp, for reasons that were never explained to him. His performance is alienating in the worst way.

But in the end, gore won out. Despite bad and bizarre performances from Arnold and his co-stars, Playboy employees Astrid Olsen and Connie Mason, “Blood Feast” grossed $4 million, a staggering return. The distribution of that small fortune caused a decades long falling out between Lewis and Friedman, as well as a prolonged legal battle with silent partner/movie exhibitor Stan Kohlberg.

Although “Blood Feast” made Lewis’ career, it also doomed him to spend the rest of his life trying and failing to top himself; this is surely the only thing that Herschell Gordon Lewis’ career had in common with that of Orson Welles.

Lewis and Friedman worked on two more gore pictures: “Two Thousand Maniacs” (1964, pictured above), a surprisingly sturdy hicksploitation version of “Brigadoon” that follows a group of Northerners as they’re preyed upon by a haunted town of Confederate-sympathizing Civil War-era ghosts; and “Color Me Blood Red” (1965), an unremarkable horror-comedy about a mediocre painter who kills for his art that brings to mind Roger Corman’s superior “A Bucket of Blood” (1959).

“Two Thousand Maniacs” was as close to a passion project as Lewis allowed himself; it cost almost three times as much as “Blood Feast” and took a little more than twice as long to shoot—almost three weeks!—and it does look much more polished than Lewis’ debut.

The film was also a family affair, the first of many. Lewis’ son Bob helped Herschell come up with the film’s most memorable death scene, in which a victim is dumped into a wooden barrel with nails hammered into its sides and rolled down a hill. He was eight at the time. Bob Lewis grew up on his dad’s sets, helping with “The Gruesome Twosome” (1967) and “The Wizard of Gore” (1970), among other films. In time he earned an affectionate nickname from cast and crew: The Eyeball-Squeezer.

But in spite of Lewis’s ambition, “Two Thousand Maniacs” did not do as well as “Blood Feast.” The latter was shocking in its newness, so much so that censors in various states and municipalities didn’t know how to respond to it and allowed it to penetrate a commercial market reserved for safer fare. By the time Lewis’ follow-up came along, they knew what they were looking at: the work of a brilliant huckster, a salesman of shock. Lewis and Friedman had a rougher experience the second time around, especially in the former Confederate states. Though crowds still turned out, the filmmakers had fewer venues to choose from, and the movie didn’t do nearly as well as “Blood Feast.”

By the time the pair collaborated on “Color Me Blood Red,” Friedman was unhappy working with Lewis. When I spoke to Lewis in 2012, he denied that any such tension existed. “We didn’t fight about the quality of our output,” Lewis maintains. “Why would we, when each egg our goose laid was golden?”

But both Adrian Curry, author of A Taste of Blood: The Cinema of Herschell Gordon Lewis, and Mike Vraney, the man responsible for releasing almost all of Lewis’s films on DVD under the Something Weird Video line, have said otherwise. “Basically, Dave [Friedman] wanted to make a better film than Herschell [Lewis] wanted to make,” Vraney said. “And Herschell still only wanted to shoot everything in one take.”

And so Friedman set off to Los Angeles with business partner Dan Sonney, and Lewis continued to make films on his own in various genres until 1972, including the lesbian western “Linda and Abilene” (1969, pictured above) and the African-Americansploitative, not-quite-hardcore porno “Black Love.”

Several of Lewis’s post-Friedman films reflect a desire to branch out into new financial territories. He talked with Roger Corman about working on the hijacking thriller “Jackson County Jail” (1976) but it never came to pass. He eventually sold his films in the early 1970s in order to open a car rental dealership, but that also never panned out.

Lewis’ films don’t stand up the test of time, but his legacy as a salesman is as timeless as a carnival barker’s patter. The marketing and publicity that sold his films constitutes a body of work more fascinating than many filmographies.

Every time “Blood Feast” screened in a new city, Friedman and Lewis would write angry letters to local newspapers, posing as incensed priests to start a kind of reverse-whisper campaign. Friedman also got a legal injunction banning the film’s exhibition in the city of Sarasota, Florida; Friedman filed the injunction himself, posing as a disinterested party and demanding that the judge stop the film from being screened. After the injunction was granted and local interest was piqued, Friedman filed a counter-suit, this time posing as another disinterested party. Friedman’s “plaintiff” in the counter-suit said that he had seen “Blood Feast” and disagreed with the original injunction-seeker’s description of it as immoral smut, because it was really “an education film.” Somehow, this tactic also worked. After the judge lifted the injunction, “Blood Feast” had had a built-in local audience that had followed the “legal battle” over the movie via local media.

After Friedman’s wife Carol described “Blood Feast” as “vomitous,” Lewis had souvenir barf bags printed up. They were white. On the side was a warning, in red lettering: “You might need this when you see ‘Blood Feast’.” He sent actors dressed as nurses to distribute them at theaters. Friedman and Lewis also took a page from the playbook of Friedman’s mentor and idol, Babb, and printed 5,000 copies of a novelized adaptation of the film script to spark the interest of exhibitors. Unfortunately, this gambit did not work as planned: when the filmmakers gave away the novels at a theater owners’ convention, many of them wound up in the trash. But these, too, have become part of the legend of “Blood Feast”—souvenirs from a time when it was still possible to manufacture outrage with pocket change and a bit of ingenuity. Decades later, John Waters bought a copy of the “Blood Feast” novelization on eBay. He keeps it in a sealed Ziploc bag and counts it among his prized possessions.

Lewis was not an artist you could get too close to, much less one whose work held deep truths and enticing secrets. He would be the first to tell you that he made his movies to make money. Aesthetically, his films don’t hold up to scrutiny. But his drive to make a profit has cast a long shadow over the horror genre since 1963, and he remains an icon to generations of horror filmmakers who sell violence the way an earlier generation sold sex: as something you felt you needed to see because someone else told you shouldn’t.