For over half a century, Edward Albee was the greatest American playwright. His most famous play “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1962) was partly meant as an answer to Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh” (1946), which repeatedly comes out in favor of illusions and pipe dreams that get a few Bowery drunks through another day. The youthful Albee was disturbed by O’Neill’s message in that play, and so he wrote “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” in response. In 1966, it was made into a movie starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton that has since become a classic. Taylor was too young for her part but she acted the hell out of it anyway, while Burton touched levels of self-loathing in that film that look extremely personal and raw.

George and Martha in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” are an academic couple all bound up in infantile aggression and fantasies and marinated in lethal amounts of alcohol. When Albee started writing it, he called this play “The Exorcism,” and it is about many things, but it is mainly about letting go of illusions and coming to terms with the truth. “Truth or illusion, George,” Martha says toward the end of the play. “You don’t know the difference.” But George does know that difference and Martha does, too. They have forgotten it and they must remember it. They must remember that the imaginary son that they created together isn’t real.

Albee was adopted by a wealthy and very cold couple named Frances and Reed Albee two weeks after he was born in 1928. As a very young man, Albee broke away from his adoptive parents and lived the life of a Greenwich Village bohemian, often drinking all night with his older musician lover William Flanagan (they made for a surly pair who were known as the Sisters Grimm in the underground Manhattan gay bars of the 1950s). Albee first came to prominence with a one-act called “The Zoo Story” (1958), which is about a conventional man named Peter who encounters an unconventional man named Jerry while sitting on a bench in Central Park. Peter has a wife and Jerry does not. There are moments when it seems like this might be some kind of a sexual pick-up between them, at least from Jerry’s point of view, but Albee moves far past this possibility very quickly.

Albee was adopted by a wealthy and very cold couple named Frances and Reed Albee two weeks after he was born in 1928. As a very young man, Albee broke away from his adoptive parents and lived the life of a Greenwich Village bohemian, often drinking all night with his older musician lover William Flanagan (they made for a surly pair who were known as the Sisters Grimm in the underground Manhattan gay bars of the 1950s). Albee first came to prominence with a one-act called “The Zoo Story” (1958), which is about a conventional man named Peter who encounters an unconventional man named Jerry while sitting on a bench in Central Park. Peter has a wife and Jerry does not. There are moments when it seems like this might be some kind of a sexual pick-up between them, at least from Jerry’s point of view, but Albee moves far past this possibility very quickly.

Albee always righteously condemned the homophobic notion that “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is actually about gay men rather than a middle-aged heterosexual married couple and a younger heterosexual married couple (Nick and Honey) who do not have children and are somewhat obsessed by that lack. His major artistic concern, in fact, is heterosexual marriage, and no writer has written better about that subject, from “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” to “A Delicate Balance” (1966) to “Seascape” (1974) and on to the under-valued “Marriage Play” (1986) and “The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?” (2002).

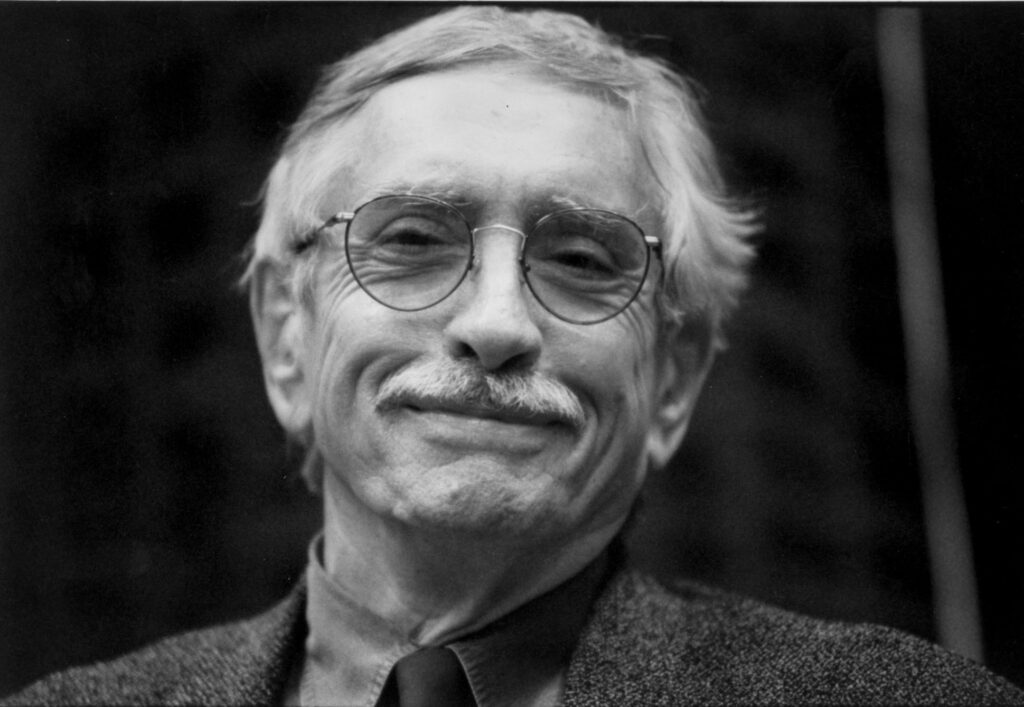

The playwright’s public image was always stern, even dour, especially in the 1970s when he grew a droopy mustache and drank to excess. He also took to publicly attacking those he thought had sold out to commercialism and escapism. But as Albee grew older and made a storied theatrical comeback in the 1990s with “Three Tall Women,” his eyes seemed merrier, his thick, low, haughty voice more flexible and relaxed. Yet Albee still lived up to his reputation as a scourge and something of a terror, seeking to control his plays down to the last pause and emphasized word.

Albee’s plays were events in the Manhattan theater world of the 1960s and through most of the 1970s, and they became that again in the 1990s and 2000s as new plays and revivals (a word he hated) of his older plays sometimes competed with each other. I was stunned (not too strong a word) by the 1996 revival of “A Delicate Balance” on Broadway with Elaine Stritch, George Grizzard, and Rosemary Harris, which revealed that text as probably his greatest play of all. There had been a film of it made in 1973 starring Katharine Hepburn and Paul Scofield that was little seen, and it is very well cast and worth investigating as a fit double bill with the “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” movie of 1966.

I saw “The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia” three times on Broadway in 2002, and I met Albee socially in this period. I even interviewed him, which was a little like trying to take a hot shower that keeps hitting you with freezing cold water. “I find it easier to work with articulate characters than inarticulate characters,” he told me. “Language is like classical music. There is a great relation between drama and a string quartet.” We talked about “The Goat,” which had just closed. “‘The Goat’ has become popular with a thinking, intelligent audience, which, of course, limits its run,” he joked angrily. He spoke at length against “self-delusion” in America. I told him I liked seeing him smile when he won the Tony for “The Goat,” and this made him relent a bit. “Well, in life, one or two things happen to make you smile, now and again,” he offered.

I kept on reviewing revivals of his plays, and I was one of the few writers, unfortunately, to give a positive review to what turned out to be Albee’s last new play presented in Manhattan, “Me, Myself & I” (in 2010) with Elizabeth Ashley—I’ll never forget the large fire truck that unexpectedly emerged from beneath the stage accompanied by trumpets at the very end of that production, a real coup de théâtre.

Albee was a scathingly unsentimental man and had been in ill health for a while. But his death is still a keen and a nasty loss to the theater world, maybe because there will be no more new Albee plays that he can oversee (hopefully we will finally get to see some version of his play about the Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca in New York). On the TV show “Theater Talk,” Albee once flippantly called death “a waste of time,” a typical bleak joke. What a shame that his time is now being wasted.