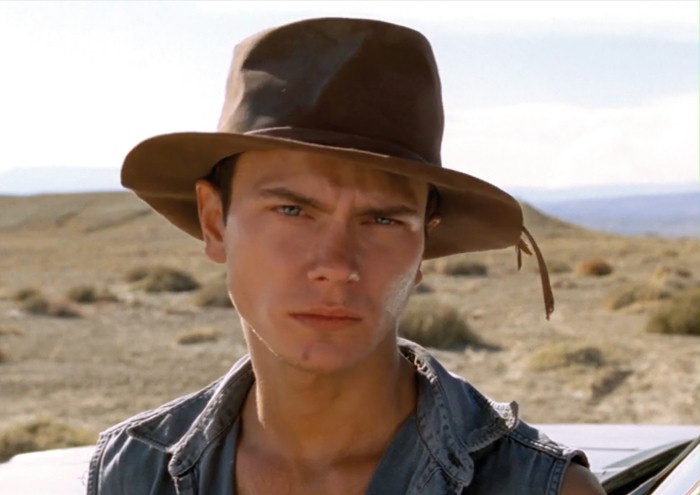

At the end of October it will be twenty years ago that River Phoenix died of cardiac arrest caused by a drug overdose outside The Viper Room club in LA. He was just twenty-three years old. He had given one major performance already, as the vulnerable narcoleptic male prostitute in Gus Van Sant’s “My Own Private Idaho“(1991), and several others, like his Marine in Nancy Savoca’s “Dogfight” (1991) and his son of political radicals in Sidney Lumet’s “Running on Empty” (1988), that showed promise and inventiveness. Even as a child actor, Phoenix was never winsome or ingratiating. He had a wary, dismayed, adult face, and a rather blunt way with emotions. He did not smile easily. And he seemed to have things on his mind that he could not share or speak about.

At the time of his death, Phoenix had shot around eighty percent of “Dark Blood,” a drama set in the Utah desert co-starring Judy Davis and Jonathan Pryce and directed by George Sluizer, and he had gone back to Los Angeles to film the rest of the interior scenes for the movie when he died that night outside The Viper Room. It had been a contentious shoot where Sluizer and Davis had taken an instant dislike to each other and were vocal about their mutual displeasure. Davis had told Sluizer that she needed to protect her sensitive skin from the sun with a large hat, and he curtly agreed to this, but then this limitation upset him as they shot. “It’s important to know what your strengths are,” Davis said in an interview for “Premiere” magazine in 1993. “I absolutely believe in my intuition; I think that’s a great asset to an actor. The weaknesses in my personality are impatience and sometimes intolerance. Which came out with this guy George. I was very quickly, utterly intolerant of him. I decided that he was dangerous, and kept away from him.”

After Phoenix’s death, the “Dark Blood” footage was impounded by an insurance company and placed in a vault where it languished for years. According to Sluizer, when he heard that the company was going to burn the film in 1999 rather than pay to keep it stored, he somehow contrived to steal it away within forty-eight hours. Recently Sluizer was told by doctors that he was seriously ill and did not have long to live, and he was determined to use the time he had left to bring what remained of “Dark Blood” to an audience. He hired Florencia Di Concilio to write a score for the film, and he himself recorded a narration in his thick Dutch accent to explain what was supposed to have happened in the scenes that were not shot.

Sluizer’s reconstructed “Dark Blood” has traveled to various film festivals, but there are still legal issues to be worked out if it is to be shown for a paying audience. It runs eighty-six minutes, and it has a clear beginning, middle and end. What’s missing are several key scenes between Phoenix’s character, known only as Boy, and Davis’s character, a former Playboy Bunny named Buffy. The film might work in a cryptic way without Sluizer’s narration, but his voice on the track winds up being effectively suggestive. We have to fill in the gaps in the narrative ourselves, and so what might have been an iffy psychological triangle thriller in the “Knife in the Water” (1962) manner becomes something else, something predicated on incompleteness.

The footage does not feel rough in any way: Ed Lachman’s smooth cinematography captures both the blaring daytime and blue-ish nighttime out in Utah. Davis is not exactly natural casting for an erstwhile Playboy Bunny called Buffy, but that’s what makes her so intriguing in the part; you can imagine her Buffy lacerating horny men in Las Vegas with her sharp tongue and imperious manner, and also turning them on. Davis is fighting against her role in certain scenes, but this conflict she is having with the material enriches her work here and makes it feel original. Buffy is a Hollywood wife married to Harry (Pryce), a well-known movie actor whose career is in a slump. They’re out on a second honeymoon while he considers a script that might put him back in the game, and their car breaks down twice. The first time it stalls they meet a hotel owner (Karen Black in an atmospheric cameo) who tells Harry about nuclear testing that had been done in the area. The second time their car stops they meet Phoenix’s Boy, a young hermit who lost his wife to radiation sickness.

There are a couple of howlers in the dialogue, most of which are delivered in Sluizer’s narration. The script (written by Jim Barton, who has not worked much since) features the kind of on-the-nose lines that might have been played outright for humor or might just have been skirted over by these three outstanding actors, all of whom were working at a very high level. Davis is at her considerable best in the film’s mid-section, a guarded woman letting her guard down, quieting her mannerisms and settling into many distinctive moods of shy yearning with Pryce and treating Phoenix with an unusual kind of tough-love tenderness.

Davis was questioning the writing at every turn, and it’s easy to understand why she was. Either you’re with this material or you aren’t, and Davis wasn’t sure if she was. “At one point when Jonathan’s character had to yell and curse at her, Judy objected to that,” Sluizer said at a festival screening last year. “I mean, this was typical: she had read it in the script and had accepted it, but once we were shooting she started to make a fuss, saying she didn’t want to be spoken to in such a way. At which point Jonathan said: ‘Ah, come on Judy, let’s keep this in. I only accepted this role because I could act mean to you!’ And that settled it. I won’t allow anyone to speak against her talent as an actress, but if we’re talking about her qualities as a human I advise everyone to keep far away from her.”

Phoenix’s Boy has created a candlelit fall-out shelter for the apocalypse he feels is coming, and he wants to share it with Buffy. Davis and Phoenix play out one intimate scene where she is stoned on drugs and he is telling her about the shelter, and in this brief interaction you can see two large talents working hard to reach each other. Unfortunately, most of the really important scenes between their characters had yet to be filmed. Phoenix had asked Sluizer to put them off because they were the hardest to do, and he wanted to get more comfortable with Davis. “The Monday after River died we all went on the set and we were asked to form a large circle,” Davis said. “George gave his speech about River—it was true what he said, he was a lovely boy. And then Jonathan Pryce asked us to join hands and wish River’s spirit a happy journey as it went across…And I felt very uncomfortable with all that. I didn’t want to hold hands, I don’t believe in spirits passing. But I didn’t have a choice, so I wished that I’d not gone to the studio. I don’t like to be forced to be dishonest.”

But here’s the thing, and this is a spoiler if you don’t want to know the end of “Dark Blood” yet. Phoenix’s Boy has been axed in the head by Harry. He knows he is about to die. Buffy comes in to comfort him on his deathbed, and he asks her to unbutton her shirt for him as a last request. Davis’s face is riven with doubt and perplexity; she is both yielding and unyielding, both Buffy and Davis, and what the script is having her do and what she herself feels about it battle together in her eyes and in the set of her facial muscles. She cradles Phoenix for a moment, and there is something about a 1993-era Judy Davis doubtfully cradling River Phoenix that pushes every one of my intellectual and emotional and nostalgic buttons.

Phoenix was so vulnerable, a poster boy for vulnerability, even, a ’90s icon, but he also had some of Davis’s harshness, and it comes out when Boy leans back and dies. This is one of the most realistic death scenes I have ever seen: his eyes and mouth open and you can see and feel when the life has left him, as if his face is just an empty envelope left on that bed. This is what someone looks like when they die, and no other actor has come as close to imagining it as Phoenix does here, in one of the last scenes he ever shot.

Asked about this new “Dark Blood” in an interview with the Guardian from this year, Davis said, “I can’t imagine what he could have cobbled together. What would be the interest in an unfinished film, other than a rather questionable curiosity in River? I don’t care personally. Makes no difference to me.” That distance she has, that refusal to be taken in by sentimentality or victim-hood or the beautiful/young/doomed in the legend of Phoenix is what makes her reluctant participation in his last scene so moving.

This reconstructed “Dark Blood” plays as pieces of a puzzle that can never quite be put together again, and it is probably much more powerful or useful as a puzzle than it would have been as a whole. It captures a point in time between two great actors who were struggling to connect and who did so in their scripted last scene where he was committed to dying and she was committed to keeping herself apart from his self-destruction but forced by circumstances and by the script to open herself up to him. I doubt I’ll see a more touching movie scene all year than this fragment from twenty years ago, this pietà of cross-purposes and disconnection leading to a tough-minded confrontation by both Phoenix and Davis of all the nothingness waiting up ahead for them, and for us.