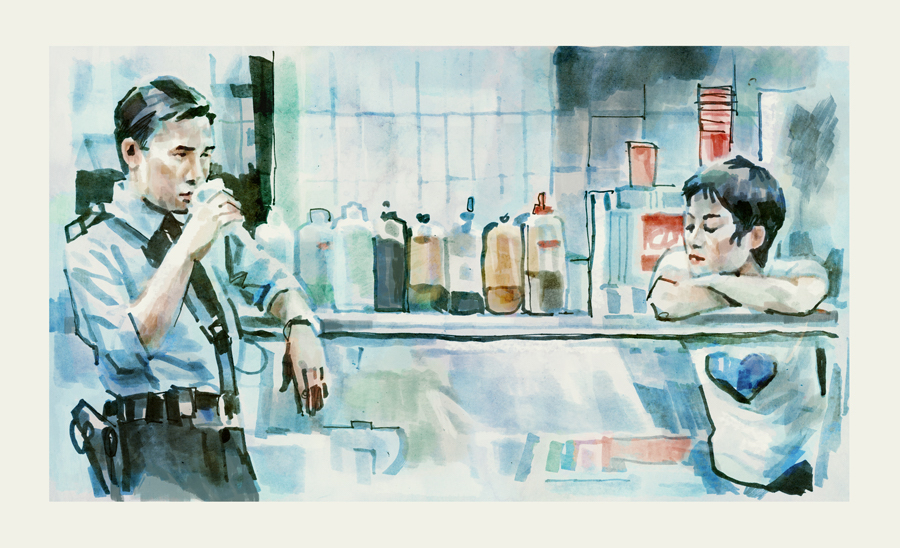

We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the March issue of the online magazine, Bright Wall/Dark Room. Their latest issue is a look back at the films of 1994, as they celebrate 25th anniversary this year. In addition to Kelsey Ford’s below piece on “Chungking Express,” the issue also features new essays on “Pulp Fiction,” “The Shawshank Redemption,” “Reality Bites,” “Speed,” “Three Colors: Red,” “Through the Olive Trees,” “Amateur,” “The Last Seduction,” “Color of Night,” “Dumb and Dumber,” and “U.S. Go Home.” The above art is by Tony Stella.

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here.

<span class="s1" <the="" hong="" kong="" of=""

The Hong Kong of Chungking Express is electric, frenetic, dense. People crowd and push and elbow, a collective urge with neon-blurred edges. Their lives are casual chaos. And yet, the characters feel isolated and lonely, separate from each other with rare exception; their melodic interiors can’t quite sync with their daily tumult.

Cop 223 (Takeshi Kineshiro) runs when he’s sad because “the body loses water when you jog, so you have none left for tears.” The femme fatale (Brigitte Lin), an exhausted drug smuggler, wears a blonde wig and sunglasses as armor. Cop 663 (Tony Leung), recently broken up with by his stewardess girlfriend, lingers around the food stand where Faye (Faye Wong) blasts “California Dreamin’” too loudly. They’re all incidental, their lives clashing before glancing away.

In an opening voiceover, as Cop 223 races through the crowded streets, he says, “Every day we brush past so many other people. People we may never meet or people who may become close friends.”

This, more than anything, informs the ethos of Chungking Express: loneliness and the hope that, maybe, someday, it won’t be quite as potent as it is now.

*

When I was a junior in college, I’d been in a long distance relationship for the better part of the last three years. It was spring and something felt like it needed to change, I needed to stop hoping my boyfriend would call me back. So I bought a copy of Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse.

At first, the act of reading the book became an act of ending the relationship, and then it became an act of getting over the loss of that relationship. I stopped three-quarters of the way through, when I no longer needed it. That book stayed on my shelf for years, the bookmark in its place. Both are gone now; I can’t remember when that happened.

Built in fragments and arranged alphabetically, A Lover’s Discourse is like a deconstructed love story. Barthes believed the lover’s discourse was one “of an extreme solitude.” As he explores “absence” and “disreality” and “silence,” he separates the one doing the loving and the one being loved. The discourse becomes less about love than about the person performing the act of love: “The lover’s fatal identity is precisely this: I am the one who waits.”

There are many ways to read A Lover’s Discourse. I choose to read it as a solitary monologue. A way of categorizing and explaining and dissecting, undoing a narrative and placing its articulated parts out like an undone body: these are the stories we tell ourselves about our place in the world, and these are the stories we tell ourselves about others.

*

Wong Kar-Wai’s lush and bright Chungking Express is built as a diptych: two stories featuring lovelorn cops wandering the streets of Hong Kong. The movie’s atmosphere and story are like one intense infatuation. The colors are bright and fast. Every object is happy or sad or filled with portent. The songs play over and over again, each time becoming more and more steeped in the emotional turmoil of the characters hitting repeat on the boombox.

In the first story, Cop 223 fixates on cans of pineapple. After his girlfriend breaks up with him on April 1st, he treats it as an April Fools joke. For a month, he buys cans of pineapple that expire on May 1st. He stacks the cans in his kitchen, an accumulation of his affection. In the movie’s signature, pensive voiceover, he says: “I tell myself that if May hasn’t come back by the time I’ve bought 30 cans, then our love will expire too.”

His frustration is bound to these expiring pineapple cans. When the market stops stocking cans that expire on the 1st, because it’s the 30th, he yells at the clerk, “With you people it’s always, Out with the old, in the with the new!” He asks, “How do you think the pineapple feels?” May 1st comes and there’s still no reconciliation. To mark the ending, Cop 223 systematically opens each can, forking the fruit into his mouth, adding spice to the slices, offering some to his dog.

On the other side of the break up and the heap of emptied cans, what’s there to do? He goes to a bar, drinks, throws up, and decides to fall in love with the next woman to walk through the front door. That the next woman is wearing a blonde wig, red sunglasses, and a raincoat doesn’t phase him. He can’t know she’s a drug smuggler. His approach is insipid and young. In three different languages, he asks her if she likes pineapple. She rebuffs him. When he says he wants to get to know her, she says, “You can’t get to know me.”

It’s easier this way, easier to turn her into an unknown, so her true edges can’t press up against the absence he’s trying to fill. The pair go back to a hotel and she falls asleep, crashed out over the bed, while he curls up on the windowsill and watches TV. He needs distraction and she needs a safe place to sleep. For one night, they’re perfect.

*

From Barthes’ entry for “The Unknowable”: “The other is not to be known; his opacity is not the screen around a secret, but instead, a kind of evidence in which the game of reality and appearance is done away with.”

A Lover’s Discourse is the negative of a love story, highlighting the moments before and after, when the narrator is alone and rolling over the story like a well-worn stone. One consistent truth he returns to: that the idea of someone is safer than actually getting to know them, that it’s always safer to leave that person in the environs of your mind, rather than allow them to violate the rules you’ve set in place for how they should behave or who they should be.

From that same entry: “I am then seized with that exaltation of loving someone unknown, someone who will remain so forever: a mystic impulse: I know what I do not know.”

*

Wong made Chungking Express during a break from another film, Ashes of Time, and the intimacy of Chungking can be sourced to its quick, two month shoot. Without permits, they had to rush any street shots; the apartment they used for Cop 663’s belonged to Wong’s longtime cinematographer, Christopher Doyle, at the time.

Wong is known for writing and rewriting his scripts while he shoots, relying on serendipity within scenes to let him know where they need to go next: “If you are paying attention, you realize that every story can go in so many directions. And each of those directions can also go in many more directions.”

In an interview with John Powers for WKW: The Cinema of Wong Kar Wai, Wong describes his style of filmmaking like the construction of a garden. “You plant a tree in the garden and you expect it will be a perfect tree. But then something happens, maybe a storm blows off a branch and you realize that it no longer looks the way you expected.” The metaphor is extended; he plants a bush, then two flowers, and then digs one up. On and on. “Then, at some point you stop, and if you’re lucky, what you have will be beautiful. It won’t be what you expected, but the garden will still be beautiful.”

<span class="s1" <this,="" too,="" feels="" central="" to="" Chungking. Our lives are hard, but sometimes, in the midst of all the furor and tension and exhaustion, sometimes there is a flicker of something nice, someone looking out for you. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, you can find a pocket of relief.

*

Chungking Express constantly doubles, even beyond its diptych structure. There are two women in blonde wigs, two stewardesses, two Mays. The characters often catch themselves in reflection, as if the image of them fragmenting along a wall feels more apt than the truth. The act of devotion is also doubled, both the end and the beginning of a romance, and the ways one can easily slip from one mode to the other.

Chungking Express is an entire movie about having a crush.

In the second story, The Mama & Papa’s “California Dreamin’” is on constant repeat. It’s a song that Wong called “innocent and simple, like summertime in the 70s” and played for his cinematographer, Doyle, when he was first trying to describe what the movie would be about. Faye blasts the song over and over again at the snack stand, so loudly she can’t hear customers or her own thoughts. This isn’t the only song threaded through Chungking; there’s also Faye Wong’s cover of The Cranberries’ “Dreams” and Dinah Washington’s potent “What a Difference a Day Makes,” which scores the flashback of Cop 663 and his stewardess girlfriend lolling around his apartment, drinking beer, flying toy airplanes, kissing against his closet.

Faye first notices Cop 663 when he starts hanging around her snack stand during his shifts. At first, he’s there to pick up meals for his girlfriend. But then she leaves him and his order becomes a simple black coffee. In the ex-girlfriend’s absence, Cop 663 imagines that everything in his apartment misses her as much as he does. “Since she left, everything in the apartment is sad,” he says. “I have to comfort them all before I go to sleep.” His soap has lost an unhealthy amount of weight, it needs to have more confidence; he tells his towels to stop crying but they continue to drip; his stuffed white bear holds too many grudges. A layer of grime has grown in the stewardess’s absence.

This is the grime that Faye scrapes away at in secret, after stashing the apartment key his ex left in an envelope for him at the snack stand. She waters his thirsty plants, buys him new towels and curtains, fills his aquarium with living fish, washes his sheets, changes the labels on his cans. His dim life livens, even if he doesn’t understand why or how.

One afternoon, he comes home while Faye is still there. In voiceover, words still heavy with loss, he says, “She used to jump out and scare me, but she hasn’t done it much recently.” He plays hide and seek, even though he knows the stewardess isn’t there hiding. It becomes a game of cat and mouse. Faye inhabits the space he wishes and expects the stewardess to be in. He checks the bathroom; Faye presses against a wall; he turns around; Faye’s ducked beneath a blanket.

Cop 663’s attentions drift from the stewardess’s absence and toward the increasingly frequent presence of Faye. Maybe he senses what she’s been doing. Maybe her proto-Manic Pixie Dream Girl vibe has gotten to him. Either way, he asks her to grab a drink with him in the California Bar, the same bar where Cop 223 met his blonde woman in shades. Faye doesn’t show and Cop 663 is left alone, a mirror of the scene where Cop 223 asked the blonde woman if she liked pineapple. There are, after all, different types of being alone.

*

“To try to write love is to confront the muck of language,” Barthes writes in his entry for “Inexpressible Love.’ “That region of hysteria where language is both too much and too little.” Which is the exact tightrope Chungking Express walks. Everything is important––every can of pineapple, every dripping towel, every loop of “California Dreamin’”––mimicking that all-encompassing feeling of infatuation. These small items hold an entire story. The heartbreak and the hope and the waiting.

But infatuation can become a closed loop. It’s scary to step outside of it, to start talking to someone rather than something. It’s easier, perhaps, to fly across the world to California than it is to cross the street and enter the bar named California, where the guy you like is expecting you. Chungking Express understands this, and the moments when its characters take those small risks feel like rewards. It’s worth it to be careful.

It takes time, yes, but eventually Faye finds her way back to the snack stand. Now she’s the one in uniform, a stewardess on leave, and Cop 663 is the one behind the counter, having bought the stand from Faye’s former boss. Faye’s energy is like a spiral about to snap. At any second, she might leave. But then Cop 663 asks her to draw him up another boarding pass; the ink on the one she’d left him the year before had long faded. So, she doesn’t leave.

This time, she stays.