We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the December 2022 edition of the online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room. Their theme this month is “Romance Comedies,” and along with this Fran Hoepfner essay about “Design for Living,” the issue includes pieces on “A Woman is a Woman,” “My Best Friend's Wedding,” “Decision to Leave,” and more.

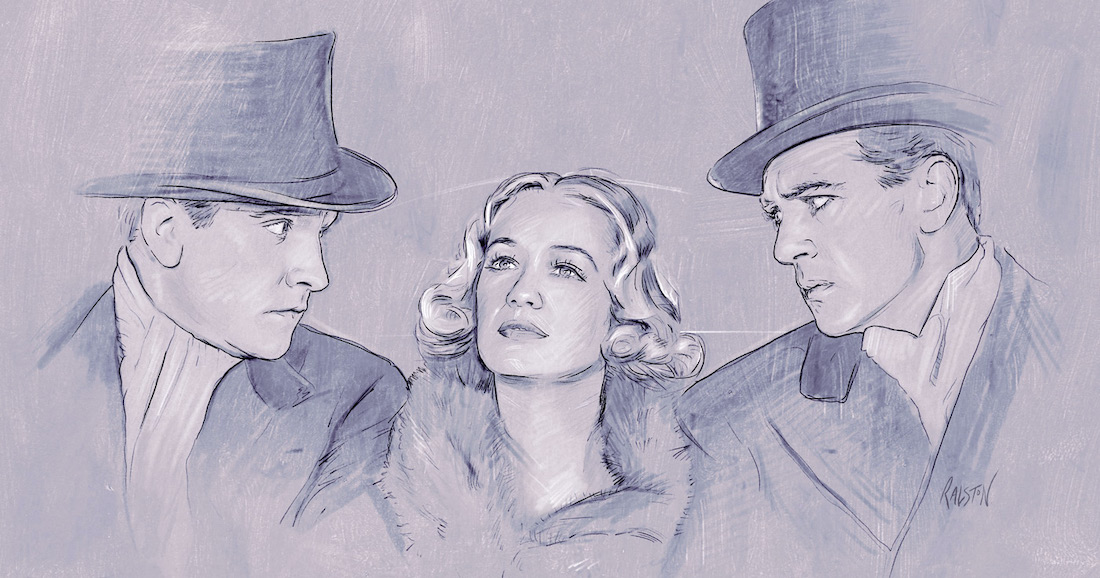

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here. The above art is by Tom Ralston.

A dilemma, maybe: can you have two boyfriends? Contemporary (which is to say coastal and/or French) society says, “Sure, why the heck not?” Even the most prudish types have come around on nontraditional relationships over the past few years; it’s not like these are threatening society more than, say, rising ocean levels. The acquisition of two boyfriends is not only possible, it is perhaps encouraged. Hot girl summer, sure. Hot vax summer—yes, we remember it well. It’s a time to be horny; we’re all always thriving. As long as it’s ethical, the dating apps will promise you, two or more is better than one. What did one person ever get out of one other person, anyway? It’s time to grow up. The tides are changing (literally) and more is not less but more.

This is now, but this is also the early 1930s. The times aren’t all that different when you think about it. We have immersion blenders and they didn’t. Beyond that, however, there is rising fascism and a perceived threat on conventional morality. People are poorer than ever. The government is useless, if not loathed—the promise of aid is far more of a mirage than any kind of practiced reality. So people are desperate and they are curious, not only for a life lived well but a life lived together. The greatest threat of these times and our times is that we will allow the profound stressors of contemporary living to divide us and provoke us, when really it should force us together, into tiny apartments and train cars, into relationships amorous or platonic or somewhere in the dreamy in-between.

The romantic, if not provocative, landscape of then and now is the setting for Noël Coward’s 1932 play Design for Living, adapted (somewhat) by Ernst Lubitsch and Ben Hecht in their 1933 film of the same name. The stage show and the movie tell essentially the same story, give or take a few hundred lines: a headstrong young woman tries to decide between two men, best friends at that—vying for her attention before all three of them realize that the answer is: maybe, just maybe, you can have it all.

The young woman in question is named Gilda (the great Miriam Hopkins), and she is a woman in business. She is astute and smart with money, a real self-made dame if I ever saw one. She is a designer for an advertising firm. Her art, though fun, is thoroughly commercial. It pays the bills. On a dozy afternoon train, she crosses paths with hunky bohemians George (a painter) and Thomas (a playwright). They think they’ve struck gold with her. To be clear, they have: Gilda is one of a kind. But trying to figure out who “ends up” with her will cause them all a lot more trouble before they’re free and easy.

First, of course, there’s the matter of living: can they all cohabitate successfully? Do their jobs, make their art, and have no sex? Sounds tricky, but I’ve always admired optimists. Gilda and George and Thomas are fallible, though, maybe miraculously so. When Thomas goes away for work, she takes up (that means “has sex”) with George; when Thomas returns, she takes up with him. The men discover the profundity of the other’s betrayal—wasn’t the agreement that no one would have sex, rather than that Gilda would have twice as much? There’s got to be a solution, another option, perhaps a more stable, sexless man in Gilda’s life that she can commit to, rather than these deviant and jealous and petulant men.

I was always told that there is nothing like making a pro/con list when it comes to shuffling through choices. Everything seems possible when it exists amorphously in your head, but once it’s etched onto paper (or a website), a choice becomes clear. Gilda doesn’t do this in Design for Living, but lucky for her, nearly a century later, I am willing to do that work for her, free of charge:

I. George Curtis

A brief survey of the uninformed (casual Letterboxd users) suggests that if forced to choose, the obvious beau of Lubitsch’s Design for Living is George Curtis, played by hunk eternal Gary Cooper. George is a painter—how romantic—and he’s so handsome—duh—with his chiseled jaw and lopsided smile. Cooper brings to the table an undeniable It factor. It’s not only that George is good-looking and artful, it’s that he’s also kind of a cad, but not fully committed to being one. That’s where a man is really in the pocket: he seems bad, and he’s a little bad, but he’s not all the way bad. Consider his portrait of Lady Godiva, naked and on a bicycle. Nuanced? Not especially. Risqué? Depends on the audience. Uncomfortable? Without a doubt.

What is most attractive about Curtis, of course, is that he’s available. Is any artist ever really working? Not consistently, and not with any kind of momentum, especially if there’s a woman around. Of course, he’s also a bit rash and prone to anger. He pouts, he grimaces. He’s—what do they call it?—the strong silent type, which is all well and good until you need him to say something in a moment of need.

II. Thomas Chambers

A contrarian, such as this writer, might present the alternative: that Thomas Chambers, as played by Fredric March, is the real catch of the film. Consider: even the most unsuccessful playwright (and Chambers is highly unsuccessful) does way more work than a painter. What does a painter do? Think something up and render it physical, lewd, and obvious. A playwright, on the other hand, imagines a whole world composed of characters big and small. He listens to the way people talk—both to and around him—and transposes it into a performed language that feels otherwise altogether new.

Of course, a writer is a dime a dozen, and one has to consider the gangly height and goopy ears on the side of March’s face. If put side to side, as they often are in Design for Living, March is less handsome than Cooper. It was true then and it’s true now that the more handsome man, objectively, is often the less handsome man, subjectively. He is interesting to look at, which never won’t sound like an insult, but why fuck with anything less than interesting. Unlike his paint-spotted comrade, Chambers is not only intrigued by Gilda but willing to drop everything at a moment’s notice to get a few seconds with her here and there. He’s easily distracted and willfully waylaid. He’s also kind of whiny, which is not a dealbreaker, but it’s not a dealmaker, either. We’re looking for a boyfriend, mind you, not a baby.

III. Max Plunkett

Don’t date your boss. In an old journal of mine from nearly a decade ago, I once wrote: “Why is it that everyone I am attracted to has control over whether or not I get a job?” Though Gilda is far quicker than I was to realize this (a few months, or about 30 minutes of the film), her longtime boss, Max (Edward Everett Horton), who pines and lusts for her to a greater extent than even he realizes, is not the answer. Long story short: bad call.

IV. Ernst Lubitsch

Okay, Gilda doesn’t actually have to, like, decide between three men and the director of the film adaptation of the play from which she originates, but it’s much to Lubitsch’s credit that this premise feels so light and unpretentious. These are the twilight hours of the pre-Code era, when lush desperation onscreen still feels sexy rather than sinful. Lubitsch, a German-born director, was known for the deft humanity in all his work, plenty of which can be credited to the fact that he was making movies in the pre-Code era far longer than he ever was after it.

And sure, some smug sophisticates will invoke his name when referencing You’ve Got Mail’s ties to The Shop Around the Corner, but the modern rom-com, at least prior to the sexless Netflix drivel, owes all it’s got to Ernst Lubitsch. For Lubitsch, it’s not necessarily that these relationships onscreen are do or die; it’s just love, that’s all, and whatever comes with it. Confusion, frustration, bafflement, contractual obligations to finish art projects before being allowed to have sex—it’s all fair game. In weaker, lesser, dumber hands, Design for Living is a movie about three horny morons; in Lubitsch’s, all three characters spark and sparkle, an abundance of wit powering them through reckless indecision.

V. Gilda Farrell

It’s tempting to be pedantic because it’s fun to be pedantic, but the film is called Design for Living not because it’s instructional but because it is, in fact, design. This is an artful interpretation of living, not a command. What is the reason behind “design” anyway? Why do we ache and yearn for apartments that are not “cheugy” but “hygge”? Why do I personally get anxious upon entering an apartment with bare walls and magnet-free refrigerators?

A life without design is a life hardly worth living. This is, perhaps, a first-world complaint, but if the years of scrimping and saving and starving artistry have convinced me of anything, it’s that artfulness can be found for any price whatsoever. This confident optimism, the one that makes me feel as though I can write on a film, any film, so boldly that I demanded an assignment from my editor rather than pitch my own take (besides, you don’t need me to go long on Sleeping with Other People), is embodied with flamboyant free will by Gilda. The movie is Gilda; Gilda is the movie. It is a design for her living much more than it is for the men who vie for her attention.

A lesser film has pining, a lesser film has a big emotional moment. Design for Living is a comedy, of course, and those flagrant displays of emotionality would make it maudlin, but it stealthily avoids cuteness. Though Gilda is playful and winsome, she is also keen and astute. “A man can meet two, three, or even four women and fall in love with all of them, and then by a process of interesting elimination, he is able to decide which he prefers,” she explains. “But a woman must decide purely on instinct—guesswork—if she wants to be considered nice. Oh, it’s quite all right for her to try on a hundred hats before she picks one out.” Design for Living is perhaps best known as a quotable film, dense with jokes and asides, but for me, it’s a film about the liberation of self, of perception, of leaning all the way into making a choice to have more. That Gilda decides not Thomas or George but rather Thomas and George suggests there is a richer life that is available to a brave enough soul willing to opt for it.

She does not execute this perfectly, however: that Gilda stumbles through a decision that feels obvious is part of her journey. First, there is the arrangement—all friends, no sex. That lasts what, like a day? And then she swings in the opposite direction towards her prudish, preening boss. But Gilda is a businesswoman, and if business people know anything, it’s problem-solving. Her issue is not that she has a bevy of men; her blessing is that she has a bevy of men. The issue, perhaps, is “society,” but, cloistered away in France, hopefully Tom, George, and Gilda will be safe a long while, free of judgment and side-eyes.

The Hays Code falls on Hollywood the year after Design for Living, Icarus tumbling from the sky, but it’s good to know how close it got, how revolutionary and modern the films—this film—felt before it all got hemmed in by prudence and fear. Three square meals might make a day, but they don’t make a life. For one, there’s always got to be room for dessert.