“There’s a dynamic mechanism to art that affects the viewer, rooted in formal engineering, the same way a poem gets its charm from the construction of a meter and accents of vocabulary, or in painting how the eye follows one element which creates an impression, which then collides with a second element in the painting; in cinema, the filmmaker uses the element of image (including shape and spatial relationships) and montage.” – Niles Schwartz, Off the Map: Freedom, Control, and the Future in Michael Mann’s Public Enemies

The author of the excellent quote above does point out, via footnote, that it’s an over-simplification of what the Soviet theorists wrote and practiced, but it’s a distillation of what works so well about Schwartz’s book, how he uses an analysis of form—not just as it is commonly referenced regarding the choices of a filmmaker but the actual conveyance of the medium as in Mann’s use of digital camerawork—to not only deeply read Mann’s highly underrated 2009 film, but the changing landscape of filmmaking and film appreciation over the last decade, and even a religious reading. It may sound like a lot to chew on for just over 100 pages, but Schwartz keeps it moving, hardly ever getting stuck in the mud of his complex assignment. Schwartz isn’t just incredibly knowledgeable about his subject matter, but able to approach it from an angle readers and viewers may not have expected.

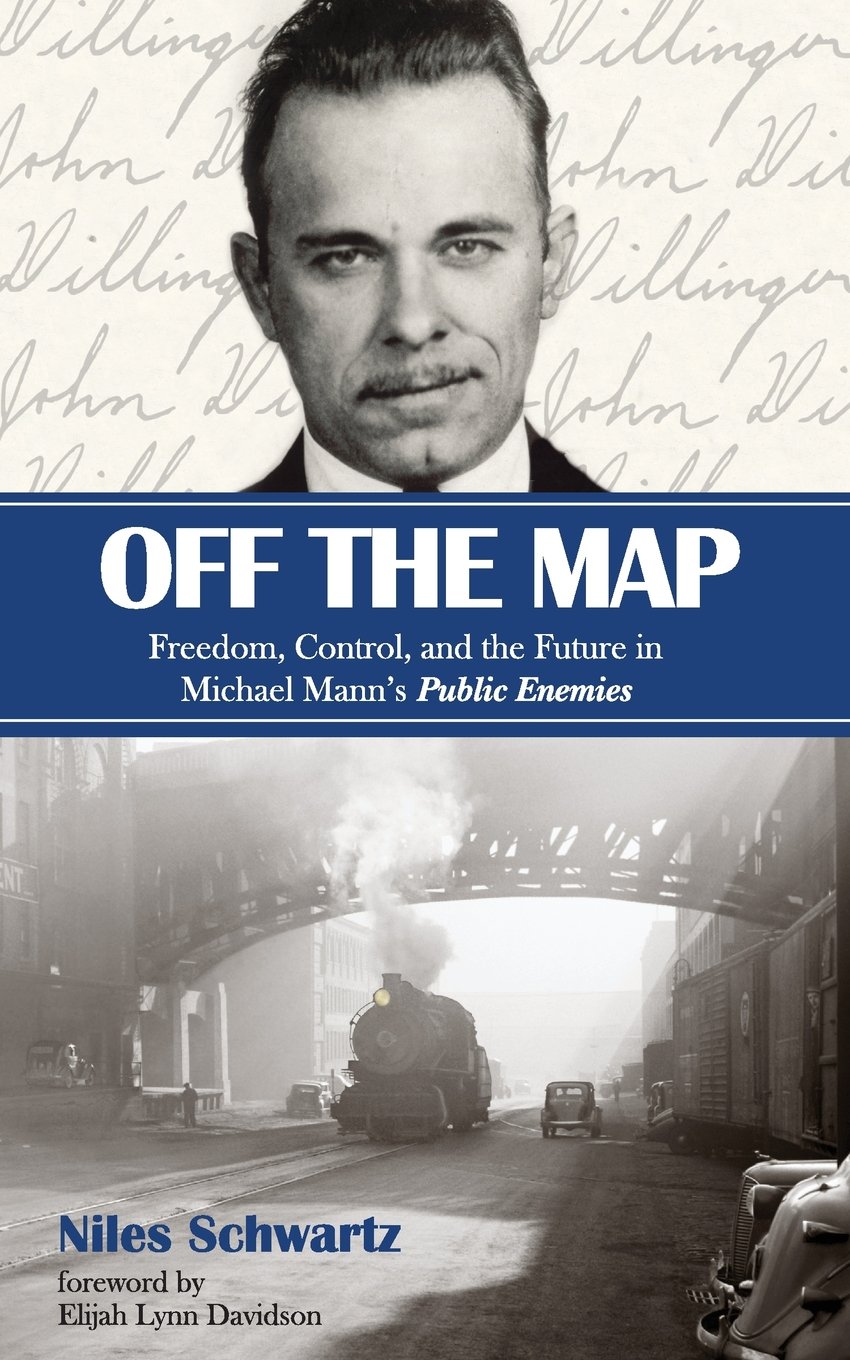

As one of the few staunch defenders of the film when it was released (as I am with most Michael Mann films … I admit to being something of an acolyte who can defend “Miami Vice” as easily as “Heat”), I remember some of the vitriol aimed at 2009’s “Public Enemies,” much of it stemming from the ‘look’ of the film. People pushed back at Mann’s use of digital camerawork, partially because they were so used to seeing tales of the gangster era with a more traditional aesthetic, and partially, as Schwartz notes, because many theaters didn’t know how to present the film correctly. They didn’t have the technical set-up for it. Now, with so many films shown digitally, “Public Enemies” looks like it was a great deal ahead of its time, and Schwartz uses this idea to allows the film to move backward and forward through history, commenting on how it both reflects the way Dillinger was keenly aware of his place in history and looks to the future of the form.

He also deftly connects that concept to Mann’s next film, the even-more-divisive “Blackhat,” a film that also uses images within images to comment on the way we digest information in the modern age. Plenty of writers have written about the way Mann uses visual language as a master craftsman, but Schwartz takes it a step further, detailing how those images are a form of commentary and storytelling for the filmmaker. He takes this dissection a step further, using the films as a framework for a look at the way cinema has developed in the age of the digital camera in the ‘10s. His certainly isn’t the first book about this and won’t be the last, but it’s one of the most interesting in a long time, especially for fans of Michael Mann. It’s a quick, brilliant read.

Note: It’s worth mentioning as a disclosure that I was mentioned positively in the acknowledgements preceding the book, something kind and unknown when I asked for a copy for review, and that our own Matt Zoller Seitz is quoted on the back. I swear it didn’t impact my experience of the book that followed. Promise.