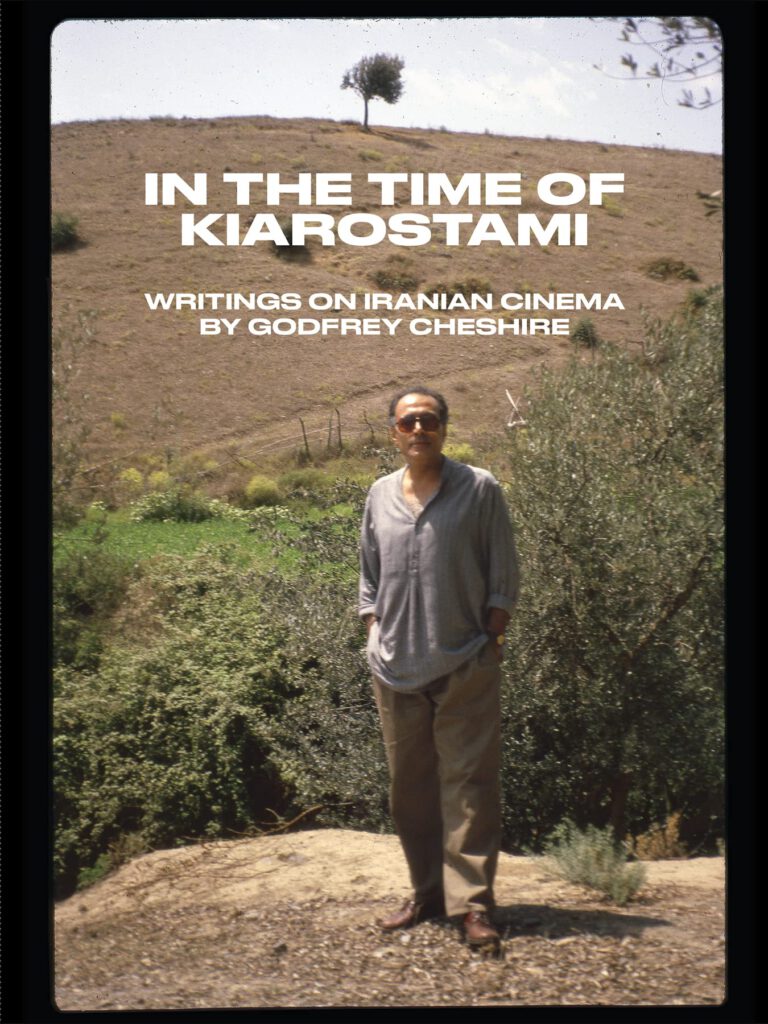

We are proud to present this excerpt from Godfrey’s Cheshire’s latest book, In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema. Get your copy here.

Besides a newly written memoir of my 30 years covering Iranian cinema, and essays and reviews of the work of Kiarostami, Panahi, Farhadi and other auteurs, my book includes accounts of some of my seven trips to Iran. This excerpt concerns my first and most eye-opening visit, in 1997. – G.C.

“Nights in Tehran”

First published April 1997 in New York Press

My first day in Iran they took me to the big “Death to America” march. I was the only American. It’s no tribute to my paltry reserves of courage to say that I was never scared, but I wasn’t. I was simply too giddy with amazement, too inoculated by a rush of adrenaline that outlasted the experience by an hour. I was, in a word, tripping. It took a while before I calmed down enough to muse that this startling cultural baptism may have reflected a deliberate, and even shrewdly benign, strategy on the part of my Iranian hosts—show him the cliché first since everything to come will explode it.

I’m not sure how many people were at this event, since I have a hard time telling the difference between 50,000 and 100,000. But there are enough to fill one of Tehran’s grandest boulevards, Azadi Street, as far as the eye could see. I was with a group of foreign visitors to Iran’s annual film festival being led on a short, escorted visit to the massive outdoor celebration, which was, in fact, in honor of Islamic Revolution Day, Iran’s holiday honoring its birth as an Islamic Republic in 1979. “Death to America” actually was no more than a prominent sub-theme, though one that easily caught my notice.

“I’m glad you don’t understand the language,” said my translator with an embarrassed laugh after a truck rumbled by filled with young men shouting slogans, their fists in the air. No, I don’t speak the language, but I understood perfectly. The gist was the same as in those various murals and mobile art displays that, for example, showed a crippled Iranian veteran riding his wheelchair over the Stars and Stripes, or Uncle Sam being strafed by jet fighters.

I had only begun to digest this—I mean, to gape at such images and feel my heart start to thump double-time—when a short, intense but generally unthreatening-looking guy ran up to me, greeted me in English and asked, “Where you from?” It was sheer reflexes combined with a stubborn disinclination to go on the defensive, I guess, that made me say immediately, “America.”

I’m not sure his mouth fell open, but he was clearly thunderstruck—for two, maybe three seconds. Then he grinned a big, welcoming grin to beat the band. I thought he was going to hug me.

No doubt it was because of the setting, but this was merely the most dramatic instance of something that happened to me over and over in Iran.

The question naturally arose a lot because I stood out like an Eskimo at a clambake. Being blond and blue eyed, I felt like I was on stage every moment that I was in public, and it never took long before someone got around to asking where I was from. The truth, it turned out, virtually assured a warmer, more interested response than I would have gotten if I’d claimed to be Czech or Canadian, say.

“Iranians adore Americans,” said an Iranian friend who lives in the U.S. Apparently they do, even when enjoying a big “Death to America” street shindig. The guy I met at the Islamic Revolution Day march fell in step with me— people were strolling purposefully, patriotically, in both directions along the boulevard; it reminded me of the North Carolina State Fair back home—and I made cautious reference to the ambient, colorful diatribes against my homeland. He waved his arm as if to say, “Oh, that—pooh! Silly stuff, pay no attention.”

I got more elaborately apologetic dismissals of the official anti- Americanism from educated, upper-class Iranians, but this guy was blue- collar, an ordinary Tehrani Joe. He was very proud of being Iranian and of the Revolution this holiday commemorated. He spoke in tones of passionate reverence about “the Imam,” as Iranians call the late Ayatollah Khomeini. As regards the apparent differences between our countries, he was equally fervent in voicing an opinion that I would hear a lot in Iran: “Iranian people like American people. People have no problem. Problem is with governments.”

A couple of days later, I heard the opposite view when a Dutch journalist told me of being at a press conference where a reporter from Time asked Iran’s president, the genial and media-savvy Hashemi Rafsanjani, what was up with this “Death to America” stuff that’s still part of Iran’s celebration of its Revolution. Reportedly, Rafsanjani smiled regretfully and said the government had nothing to do with it, it was simply the spontaneous emotion of the people.

My own impression was that public anti-Americanism at this point is basically pro forma, and that the forma is increasingly outdated. Certainly, it was current 18 years ago when the U.S. was seen as backing a Shah that a huge number of Iranians wanted deposed, just as it was current 12 years ago when we were viewed as supporting Saddam Hussein (you remember our good friend Saddam) in the grueling, hugely destructive eight-year war that Iraq and Iran fought. But much has changed in the last decade, even in the last two or three years, and today there are signs that official thinking in Iran is swinging closer to the friendly views of the man in the street—a change that won’t make much difference, of course, unless our policy makers are sharp enough to take advantage of it.

One obvious reason for this turn of events is that the Islamic Republic is no longer struggling to come into being, or to beat back the onslaught of a massively armed neighbor. It is at peace, increasingly prosperous and full of the kind of buoyant self-confidence that comes with surviving a protracted ordeal. In its government, nuanced pragmatism has rapidly overtaken the ideological purism that used to determine everything. One Iranian acquaintance, however, offered me the view that not all of the recent changes are traceable solely to Iran’s own experience.

“The collapse of the Soviet Union really made them look at things differently,” he said of Iran’s leaders.“ They were really surprised. They saw that the Soviet Union didn’t lose a military war, it lost culturally. So they started to see that that’s what Iran is in with the U.S.—not a war but a contest that will come down to culture.

Which is one angle on why this regime takes movies very seriously indeed, and why being the lone American film critic here at the moment entails a surprising amount of local celebrity (one night I’m interviewed so many times that I tell someone I feel like Sharon Stone) as well as a constant sense of fascination with the surroundings. Movies, after all, are only the tip of the cultural iceberg. When we got back on the bus after leaving the Islamic Revolution Day march, my adrenaline still surging, I started noticing the graffiti on Tehran’s walls. Besides the scrawls in Persian script, there were some in English, mainly the names of rock bands: MEGADETH and METALLIKA [sic], and my favorite of all, IRAN MAIDEN.

Tehran reminds me of L.A., and not just because both are movie capitals, the former to the international art film right now, arguably, what the latter is, perennially, to the global biz. Both cities are also sprawling urban arrivistes in countries harboring older and more elegant metropolises, and both are jammed with serpentine freeways and roads thanks to their addiction to the automobile. Since the Revolution, many, many thousands of displaced Iranians have understandably migrated to L.A. They call it Tehrangeles.

Tehran, though, seems to be winning the race to choke itself to death on air pollution. Like L.A., it’s situated in a natural bowl that produces smog-trapping temperature inversions. Most days the air makes the city look as if a gray-brown scrim covers it. On the rare clear day, the effect is startling; the snow-blanketed Alborz Mountains skirting the city’s northern edge appear as present, sharp and luminous as a diorama. Higher than the Alps, their near reaches contain three world-class ski resorts that, during my visit in February and March, are magnets for Tehran’s wealthy and athletic on the Thursday-Friday weekend.

A grandly tree-shaded and extremely long avenue called Valiasr, Tehran’s own, dustier Champs-Élysées, bisects the city, dividing east from west. A more striking cultural divide, however, cuts in the opposite direction. Like the world itself, Tehran is composed of a rich north and a poor south. And in that fact lies a defining irony: While Iran’s Revolution was powered by the lower classes (though amply supported by the others) and had a decided socialist component wedged into its intellectual framework alongside the dominant Islamic fundamentalism, it didn’t result in anything like a classless society. One encompassing look at the city tells you that.

While the city center contains all the business and government stuff you would expect, Tehran is most striking at its extremes. The southern sections are by no means squalid, and some signs—like a recent upsurge in small, clean parks backed by the city’s aggressively innovative and forward-looking mayor—suggest that things are improving rapidly. But the south still has a struggling, Third World air; you could be in Cairo. In the north, you could be in Bel Air. There are Mercedes and mansions and movie producers.

My own experience of the city changes as familiarity increases. On first arriving I am with a largish group of foreign visitors (from places including Bosnia, Lebanon, Korea and Japan) to the Fajr Film Festival. We are put up at the Azadi Grand, a posh enclave in the swanky north; its stationery bears the ingenuous legend “ex-Hyatt,” advertising its pre-revolutionary identity. Initially I like the security of the place and the group setting. Then restlessness sets in, and I begin peeling off at lunch-time and exploring the city center on foot. Eventually I move myself downtown to a hotel near Ferdowsi Square that costs about a third of what the Azadi costs. But I decide that this place is still too insulated, so I move to an establishment I discover that is, in a word, aces. I dub it the Chelsea Hotel of Tehran. The Hotel Naderi.

One of the most popular films in the international section of Fajr is Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. Seeing that Jarmusch seems to have a sizable following in Tehran, I suggest that he make his next episode of “Coffee and Cigarettes” at the Naderi. The hotel’s coffee shop has been a hangout for bohemians and intellectuals for a half century, and you couldn’t find a movie set that fits that role more perfectly. I am so awed by this place’s cool that I sometimes just sit and gaze at it long after my coffee is finished.

Granted, the hotel’s elegance is several decades in the past, and cleanliness isn’t a byword. But I met a German woman who’d been there for six months while negotiating to sell a mansion she owns in the north, and she put it well in saying, “The staff are the nicest people, and the atmosphere is just unbelievable.” The Naderi costs about $8.50 a night. But then, everything in Iran is incredibly cheap if you have dollars. It is a tourist mecca just waiting to happen.

* * *

Abbas Kiarostami, who in France and other parts of the world is considered not just the greatest of the Iranian cinema’s masters, but chief among the world’s, lives in a pleasant, unostentatious house in northern Tehran. When I go there for dinner one night late in the month I spend in Iran, I notice that the living room is decorated with lithographs by Akira Kurosawa. These, in a way, represent one Iranian’s defense against charges of ideological impurity.

When I asked Kiarostami, on first meeting him in New York a couple years ago, if he had come under suspicion for being so acclaimed in Europe, he said he had, and that it had made things uncomfortable for a while. Ironically, relief came from the most eminent of Japanese directors. When Kiarostami’s films were shown in Tokyo, Kurosawa issued a statement that said. “I believe the films of Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami are extraordinary. Words cannot relate my feelings… Satyajit Ray passed away and I got very upset. But having watched Kiarostami’s films, I thank God because now we have a good substitute for him.”

Kurosawa had spoken out similarly, it was reported, only for three other filmmakers—Ray, John Cassavetes and Andrei Tarkovsky. The endorsement from the East, Kiarostami told me, stopped the charges that he was a tool of the West.

A filmmaker facing similar problems that have yet to end, Mohsen Makhmalbaf may be second to Kiarostami in international regard, but on home turf it’s another story: He is a celebrity whose renown, as I have noted before, is comparable to that of John Lennon’s. How he got to that position is a story that could only happen in Iran.

A product of Tehran’s poor southern district, Makhmalbaf started out as an Islamic fundamentalist terrorist. Captured, at age 17, after an assault on a policeman, he was locked up by the Shah’s security apparatus and tortured for four years. When he was released by the Revolution, he still had never seen a movie, but that soon changed. An autodidact who became a prolific writer (he has now some 20 books to his credit), he fashioned himself as an Islamic fundamentalist auteur; his earliest films were shown in mosques.

Then, as his own beliefs began to shift away from orthodoxy, Makhmalbaf made a series of films (The Peddler, The Cyclist, Marriage of the Blessed) that lashed out at injustices in Iranian society and culture while championing the poor, the scorned, the disenfranchised and war damaged. It was these movies that established him as a passionately revered national icon.

Yet the fact that Makhmalbaf converted from fundamentalism to stinging social criticism to, more recently, a kind of ecstatic cinematic poetry that brings to mind Rumi has not endeared him to his former brethren among the true believers, including those in the cinema establishment. On the contrary, he has been the target of ideological campaigns, and five of his films have been banned. His most recent, Gabbeh, was recently released in Iran only after getting a personal thumbs up, I’m told, from the nation’s current spiritual leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Makhmalbaf has not taken the attacks against him lying down. Gritty and unapologetic, he has returned the metaphorical fire without hesitation, and has recently announced that he’s so fed up with the obstructions Iran puts in front of its artists that he will make his next film in India. In a conversation with German director Werner Herzog that was printed in an Iranian film magazine, Makhmalbaf seemed to sum up his entire career in a single aphorism. “It is easier to attack an armed policeman with your bare hands than to attack ignorance with culture,” he declared.

The warmest, most down-to-earth and charismatic of Iranian directors, he takes me one day to see a famous mosque in southern Tehran, where he still lives. For once, I’m not the one that everyone is staring at. Women in chadors shyly approach him and ask for autographs. Another day a fax arrives from the head of the Singapore Film Festival saying, “Gabbeh is the most beautiful film I have ever seen.” This and the eye toward India make sense: Makhmalbaf is as opposed to Hollywood’s mechanistic brutality as he is to orthodox intolerance. His spirituality, like his cinema, belongs to the East.