New York-based film critic Ethan Alter was kind enough to share an excerpt from his new book “Film Firsts: The 25 Movies That Created Contemporary American Cinema.” With the 15th anniversary of “The Blair Witch Project” taking place this year, we thought that chapter would give you a good taste of what Mr. Alter’s book is all about. He dissects the film, offering insight into its production and its impact. Alter has been published in Premiere, TV Guide, and Entertainment Weekly. He currently contributes reviews and articles to such outlets as Film Journal International, IndieWire and Yahoo Movies. Click HERE to buy his book.

The Film: By faking it so real, the makers of “The Blair Witch Project” struck box-office pay dirt and launched the found-footage horror genre.

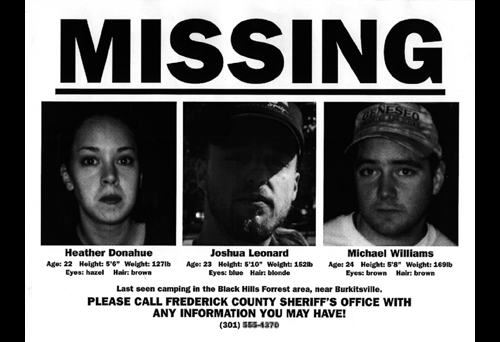

An awful lot of fiction went into making the ostensibly factual horror movie “The Blair Witch Project” a reality. Start with the premise, which is handily summarized in a title card preceding the film: “In 1994, three film students armed with more cameras than common sense wandered into the Maryland woods to investigate the legend of the Blair Witch. They never returned, but a year later the footage of their doomed trip was unearthed and presented for the world to see.” Let’s debunk this scenario point by point. First, the footage seen in “The Blair Witch Project” was shot in 1997, not 1994. Secondly, the film students weren’t actual film students, but actors who had auditioned to be part of this half-inspired, half-foolhardy production. Finally, the Blair Witch herself—along with all her accordant mythology—was an invention, dreamed up by the movie’s directors, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, and later embellished beyond the film in a series of tie-in books by other writers.

About the only thing in “The Blair Witch Project” that is authentic are the scenes of the three “students,” Heather (played by Heather Donahue), Josh (Joshua Leonard), and Mike (Michael Williams), hiking through the forests surrounding Burkittsville, Maryland. The trio really did spend several days in the wilderness, carrying their own supplies, making up their own dialogue (extrapolated from a detailed story outline typed up by the directors), and filming their journey with a pair of cameras, a Hi-8 video recorder, and a 16mm camera shooting black-and-white film. But even that nugget of truth is wrapped in fiction, as the actors were following a path prepared for them by the filmmakers, who plotted the course through Maryland’s Seneca Creek State Park with GPS units. And during the shoot, the directors regularly interacted with the performers off camera, requesting multiple takes of the same scene and passing along acting notes, story reminders. and things to react to, be they physical objects or suitably spooky noises. The cast and crew even had a special code word—“Taco”—that they used whenever they needed to escape the movie’s reality into actual reality. For a film that derives its drama and its scares from being immediate and in the moment, so much of it was carefully planned out in advance.

And yet the impressive thing about “The Blair Witch Project” is that, while you’re watching it, you don’t see the strings. Sure, there are cracks in the scenario if you laser in closely enough, especially during repeat viewings. But all that advance legwork that the filmmakers put in lends the film an internal consistency and a narrative drive that its descendants in what has become known as the “found-footage” genre often lack. A found-footage descendant like 2007’s “Paranormal Activity,” for example, operates mainly on a scare-to-scare basis, using the found-footage aesthetic (commonly defined by a first-person point-of-view camera, jumpy editing, and mockdocumentary interviews and/or confessionals, among other elements) to stage effective “Boo!” moments, but not necessarily putting a great deal of thought or effort into what comes between them. In contrast, “The Blair Witch Project” doesn’t isolate its predesignated scary bits—the scenes the filmmakers have specifically designed ahead of time to elicit screams from the crowd—from the rest of the narrative; instead, the whole movie flows together, building naturally and inevitably toward the characters’ horrific fates.

Although “The Blair Witch Project” is correctly regarded as having kickstarted the contemporary found-footage boom, which has since spread from horror into other genres, it isn’t technically the first of its kind. The obscure 1980 Italian film “Cannibal Holocaust” employed the same “group of filmmakers go missing in the woods and here’s their footage” premise, using—as the title suggests—cannibals rather than witches as its central boogeyman. And even before that, exploitative pseudo-documentaries like the infamous 1962 hit “Mondo Cane” sought to pass off faked footage of gruesome deaths and general mayhem as the real thing. Despite not being the first out of the gate, “Blair Witch” has had a more lasting impact than its predecessors, due to the deftness of its execution, the scale of its success, and, most importantly, the appropriateness of its timing. (Interestingly, the documentary approach was initially born out of financial rather that creative necessity. As Sánchez told Entertainment Weekly in a 1999 interview, “It was supposed to look like a documentary because we had no money.”) Released in 1999 on the cusp of the reality television boom—CBS’s industry-changing reality TV competition “Survivor” was still a year away, but MTV’s “The Real World” had already been through several cycles—the movie presaged a time when recording your life on a camera would be second nature, particularly amongst tech-savvy youngsters like the characters in the film. Heather, the director of the documentary within the faux-documentary, has a habit of letting the camera run, even when she’s not collecting material for her student film. When asked early on why she feels required to “have every conversation on video,” she pauses a moment before replying matter-of-factly, “I have a camera. Doesn’t hurt.” To her mind, the camera’s mere presence justifies its use; it would actually be odder to not have it running all the time.

Obviously, the movie’s central narrative device demands that Heather adopt this attitude, because if she wasn’t constantly filming herself as well as Josh and Mike, there’d be no footage for us to “find.” But there’s another level to her compulsion to just keep shooting no matter how dire their situation becomes; as one of her companions remarks at one point, by treating her life as a movie Heather is able to distance herself from what’s actually going on. Reality seems a little bit grander, a little bit more fun, and a little less horrific when viewed through a camera lens. At several points throughout “Blair Witch,” especially when their situation grows increasingly dire, her companions beg and even threaten her to stop filming, a request she can’t bring herself to comply with, insisting that, “It’s all I have left.”

In Myrick and Sánchez’s initial vision for “Blair Witch,” the plight of the student filmmakers was only going to be part of a bigger faux-documentary canvas. After the Maryland shoot wrapped, production shifted back to the filmmakers’ home base in Florida, where they started work on what they described as “Phase II” of “The Blair Witch Project,” which would incorporate additional elements, like fake interviews with occult experts and the parents of the missing students, who were actually played by actors. While reviewing and editing the footage of Heather, Josh, and Mike, however, they began to feel that that material was strong enough to stand entirely on its own.

Thus, the film’s reality was reshaped once again in the editing room, as the directors constructed whole sequences out of different takes—much like in a conventional narrative feature—and omitted or cut around the cast improvisations that didn’t fit what they wanted from the characters or the scene. For instance, Myrick and Sánchez found the tone of much of the early footage too angry, with the actors squabbling with each other before they even arrived in the woods. So they snipped those fights out while retaining the lighter, funnier moments—rendering the characters’ relationships as more harmonious than they actually were. In essence, the filmmakers were creating scripted moments out of unscripted raw material, in the same way that the majority of contemporary reality television programs do. In that industry, the task of manufacturing a dramatic reality out of actual reality falls to story editors, who employ many of the tactics that Myrick and Sánchez used in making “Blair Witch,” including recontextualizing footage, coaching the cast members on what to say in a particular scene, and dropping them into artificial circumstances that are guaranteed to generate conflict. In that way, one could make the case that a series like “Duck Dynasty” owes as much to “The Blair Witch Project” as more obvious descendants like “The Devil Inside” do.

The illusion of reality was “Blair Witch”’s main selling point and the thing that tempted moviegoers into the theater in droves. Thanks to films like Scream, the horror genre was drowning in heightened self-awareness by the late ’90s, dominated by movies that knew they were movies and took pleasure in winking at the audience in between murders. Myrick and Sánchez’s film stood as the antithesis to that in that it wanted the audience to believe that what was happening on-screen was authentic, rather than deliberately artificial. The movie’s seriousness, along with its then-unfamiliar style, is undoubtedly what shocked and surprised the first wave of audiences who experienced it during its world premiere at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival. It was in Park City that “The Blair Witch Project” first acquired the reputation as being the scariest movie to come along in years, one guaranteed to terrify even the hardiest soul. The distributor that acquired the film—the now defunct Artisan Entertainment—continued to successfully bolster that impression in “Blair Witch”’s ad campaign, aided by the breathless Sundance coverage. By the time the movie opened in general release that summer, few people knew what the movie was about, but they did know that it was supposed to be—as the Peter Travers pull quote emblazoned on one of the film’s posters promised—“Scary as Hell.”

While the hyperbole surrounding “The Blair Witch Project” raised its profile, it also put a big target on its back. Viewers walked into the theater expecting to lose their minds with fear, and when that didn’t happen, they walked out angry and confused—as well as maybe a little nauseous due to the movie’s handheld camerawork. Although the movie was successful, it also proved wildly divisive, with a significant portion of the audience not caring for the brand of horror it was practicing, one that was more rooted in psychology than blatant, in-your-face scares. The fact is, the movie’s real subject—as well as the source of its horror—isn’t the titular witch at all, but the way seemingly ordinary, well-adjusted people can turn on each other (and themselves) when placed in extreme situations. At heart, “The Blair Witch Project” is a depiction of the breakdown of the social order played out in microcosm, as well as the destruction of an individual’s sense of self. And as such, it’s more unsettling than overtly terrifying, which is bound to disappoint anyone purely looking for a steady stream of shocks and jolts.

The mixed reaction that mainstream moviegoers had to “The Blair Witch Project” may be one of the reasons why most of the found-footage horror films that came after have employed the style to more conventional ends. For example, “Paranormal Activity” and its sequels are little more than straightforward haunted house stories complete with a ghost that goes bump in the night, while “The Last Exorcism” incorporates many of the same devil-based theatrics made famous by William Friedkin’s 1973’s smash horror hit “The Exorcist.” In both cases, the faux-documentary style is primarily a gimmick to deliver familiar scares in a semifresh way. Intentionally or not, “Blair Witch” possesses higher aspirations; it’s using documentary elements not necessarily to make the story authentic, but rather to make the feelings inspired by the story—fear, rage, and despair—authentic. The footage may be fictional, but the emotions are real.

The First: At the dawn of the Internet age, it took an independently financed horror movie with limited resources to show Hollywood how to harness the marketing power of the World Wide Web.

For perfectly preserved examples of what online movie marketing looked like in the early years of the Internet, point your browser in the direction of the still-functioning sites for the films “Space Jam” and “You’ve Got Mail,” released by Warner Bros. in 1996 and 1998 respectively. Both sites were built, launched, and maintained by the studio to function as an additional advertising arm for its Bugs Bunny/Michael Jordan basketball comedy and Tom Hanks/Meg Ryan romantic comedy and bear all the hallmarks of early webpage design—from limited graphics and lots of text to a small color palette and blocky frames. Beyond their retro design, what stands out about both sites when visited today is how perfunctory they feel. While each contains a fair amount of content (particularly the “Space Jam” site), neither does a particularly strong job selling visitors on the experience of seeing the movie. That makes sense as, at the time, television and print advertising was still the primary way that the studios marketed their wares to the general public; the Internet was still an addendum to the marketing campaign rather than the integral part it has become today.

Even as the Web’s toolkit—to say nothing of its reach—grew during the ’90s, the deep-pocketed major movie companies mainly stuck with the traditional (and pricey) advertising methods, leaving the exploration of the digital frontier up to outsiders like the makers of “The Blair Witch Project.” From the beginning, Myrick and Sánchez seemed well aware that getting their independently financed feature seen and released would, in many ways, pose an even greater challenge than getting it made in the first place. By the time the duo began shooting Blair Witch in 1997, the indie film industry had become a big business, and while that meant that the market for low-budget, convention-defying movies was larger than before, it was also that much easier for films to get lost in the shuffle, either on the festival circuit where they all vied for the attention of the same distributors or, if they made it that far, in theaters.

But Myrick and Sánchez were also fortunate in that their movie came with a salable hook—namely, was “Blair Witch” fact or fiction? Unlike today, where found footage has become a genre unto itself, in the late ’90s, there was still the potential to persuade moviegoers that the film’s manufactured reality might in fact be the real deal. (The illusion was further bolstered by “Blair Witch”’s deliberately amateurish camerawork as well as the fact that the three young stars were complete unknowns.) The directors made the question of the film’s authenticity a selling point early on, when they were still making the fund-raising rounds to finance the feature in the summer of 1997. One person who saw potential in the idea was indie film producer/booking agent/gadfly John Pierson, who invited Sánchez and Myrick to air part of an early test reel they had done for the film—along with additional material that he would finance—as a segment for his television series “Split Screen,” which was wrapping up its first season on the cable channel, IFC. The show presented the footage as fact, and after the episode aired, the filmmakers were excited to learn that viewers seemed to believe it. By October, the funding was in place, and the Blair Witch cast and crew walked into the woods for a roughly weeklong shoot.

The following April, footage from the now-completed “Blair Witch Project” was once again featured on “Split Screen” as part of the show’s second-season premiere. But a more significant milestone occurred in February 1998, when the directors launched the first version of the film’s website, blairwitch.com. Initially, the site featured very little in the way of information, offering up the wholly invented explanation that potential legal issues were preventing the filmmakers from going into more detail about the footage featured in the film. (Although that might seem like a too-convenient-to-be-believable dodge, it wound up piquing the interest of more than a few visitors; in one of his journals, Sánchez describes being contacted by a detective wondering whether the site’s description of three missing students was real. They eventually made the decision to let him on the secret.) The traffic to both blairwitch.com and haxan.com (the official site for Haxan Films, Myrick and Sánchez’s production company) experienced a major bump after the movie’s second “Split Screen” airing, with posters speculating about its veracity, a debate that the filmmakers allowed to play out without tipping their hand. Then in October 1998, a caller to the popular Los Angeles–based morning radio talk show “The Mark & Brian Show” spoke about the movie and its website on-air, a mention that brought the site 2,500 visitors in only two days. The advance attention undoubtedly came in handy when “The Blair Witch Project” was admitted to Sundance, helping attract capacity crowds to the film’s first festival screenings.

After Artisan acquired “Blair Witch” at Park City, they directed the filmmakers to continue developing the site, adding copious amounts of content that bolstered the movie’s (false) claims to fact, including purported police photos, interviews with fictitious experts, and an invented mythology for the Blair Witch herself. As the film’s midsummer release drew closer, blairwitch.com was attracting two million hits every day, and visitors professed to being alternately fascinated and frightened by the film’s carefully crafted imitation of real life.16 The website proved such a powerful marketing tool that Artisan made the decision to bypass paying for any thought-to-be requisite television commercials—although the film did receive some TV play in the form of an hour-long special made for the Sci-Fi Channel entitled “Curse of the Blair Witch,” which again presented the case of the missing students, as well as the unearthed footage of their hike, as being real. All that online buzz paid off handsomely when “The Blair Witch Project” opened theatrically on July 16; initially released on 27 screens, the film earned $1.6 million in its first weekend, a number that swelled to $140 million by the end of its wide release run.

To this day, “Blair Witch” remains one of the most profitable independent films ever released, and much of that success can be attributed to the innovative way it used the Internet to attract the kind of attention for free that the bigger studios generally pay top dollar for. Blairwitch.com didn’t just blandly sell the movie; it offered visitors a unique experience that existed separately from the film while still reinforcing the title and central concept in people’s minds. In the wake of “The Blair Witch Project,” the Internet’s role in movie marketing underwent a reassessment in Hollywood’s boardrooms, with a greater emphasis placed on incorporating user-friendly original content ranging from games and exclusive behind-the-scenes videos to galleries of artwork and fan competitions. Today, virtually every blockbuster released by a big studio has a major Internet presence that encompasses a tricked-out website along with a Facebook page, a Twitter feed, and even a Tumblr account. If “Space Jam” or “You’ve Got Mail” were made in the present, it wouldn’t be enough for them to simply have a website; they’d be expected to provide a full-fledged web experience.