A bigot walks into a bar and won’t stop venting his spleen. He meets a businessman with blood on his hands. The knockout punch line, largely lost to history, is “Joe.”

By the end of the 1960s the movie industry had absorbed the desires and viewing habits of the counterculture. More and more films were designed to appeal to a young audience, from runaway hits like “Bonnie and Clyde,” “The Graduate” and “Easy Rider” to the overflowing raft of exploitation films that set sail earlier in the decade. In the wake of Woodstock, even in the wake of Altamont, Hollywood’s hair wasn’t just down; it was swinging.

But in culture, as in politics, action creates reaction. Richard Nixon won the 1968 presidential election by appealing to the “silent majority” of voters who thought the ‘60s had gone too far and craved a dose of the “law and order” that Nixon promised. From this environment sprang a new niche: the counter-counterculture movie.

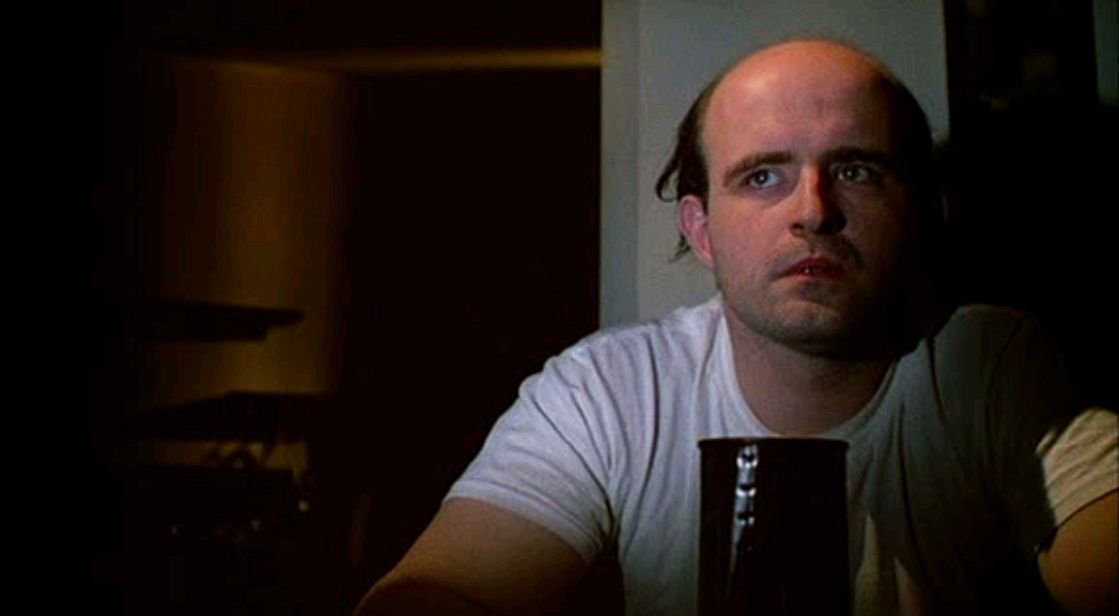

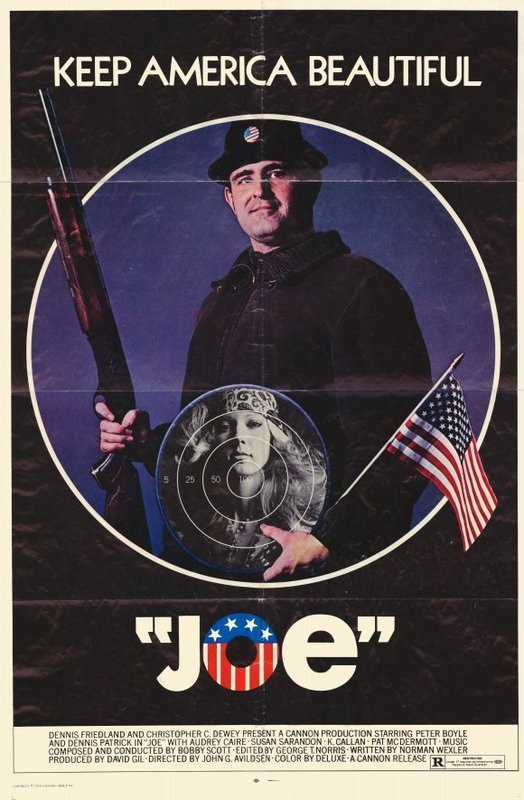

The counter-counterculture film was often an action drama: “Dirty Harry,” say, or “Death Wish.” But it could also wield a sharp satirical edge, as in John G. Avildsen’s “Joe” (1970). The eponymous antihero, a factory worker played by Peter Boyle, befriends a businessman (Dennis Patrick) in a dive bar. The businessman has lost his temper and bludgeoned to death his daughter’s boyfriend, a sneering heroin addict who hooked said daughter (Susan Sarandon, in her first film role). Joe is a scabrous caricature of blue-collar resentment, a casual and vociferous racist who finds the accidental homicide committed by his new friend pretty neat. He’s the silent majority mutated to grotesque form.

“Joe” could be described as a hardhatsploitation movie, a lurid, violent, and darkly funny snapshot of two social classes finding common ground over hatred of those damn hippies. The film dramatized the bond forged between two groups—aggrieved blue-collar workers and fat cat businessmen—that were rapidly becoming the backbone of the Republican Party. It offers an interrogation of issues and emotions that divided America as the ‘60s became the ‘70s: civil rights, worker resentment, Vietnam, broken ideals and splintered families. “Joe” reflects the country’s rightward slant of the times, but it’s also intrigued by the causes and effects of this slant. It holds a cracked mirror up to a turbulent period, and it reveals a swirling prism of a country teetering on the edge.

If, as Peter Biskind argues, the films of the ‘50s reflected “the decade in which it seemed that the United States had solved most of the basic problems of modern industrial society,” then the films of the ‘60s showcased a national crack-up. Rick Worland writes, “filmmaking of the era unfolded against the most tumultuous period in American history since the Civil War.” The consensus that Biskind described exploded into chaos. Race riots broke out in Detroit, Los Angeles, Newark and other major cities across the country. The Vietnam War raged, with young minorities making up a disproportionate number of casualties. At home, protests against the war picked up steam through the second half of the decade. 1968 alone saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy.

Also in 1968, Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign courted a coalition of those who saw the counterculture as an impediment to recapturing the good old days. “To me law and order must be combined with justice,” Nixon said in a typical sound bite from a televised town hall discussion, filled with questioners handpicked by Nixon’s media consultant, Roger Ailes, who, 28 years later, would make a right wing ratings giant out of Fox News. “I want to provide the kind of law and order that deserves respect.” In planning the event, Ailes described one of his ideal questioners: “A good, mean, Wallaceite cab-driver. Wouldn’t that be great?”

Or, how about a good, mean factory worker? The first words out of Joe’s mouth are an eruption of broiling barstool racism that can’t be printed here. Norman Wexler, the 42-year-old Harvard-educated advertising executive and unproduced playwright who wrote Joe, had figured out how to bring the Nixon camp’s rhetoric down to the street, and then into the gutter. As J. Hoberman writes, “Joe expressed sentiments that no politicians—not even George Wallace—had the nerve to articulate, at least not in public.” And in May 1970, when a band of construction workers and businessmen attacked protesters marching in New York’s financial district to protest the Kent State massacre and the Vietnam War, Wexler and director John G. Avildsen realized their forthcoming Joe might just be the movie for the moment.

“Joe” was originally to be titled “The Gap,” and it was supposed to focus on the chasm between businessman Bill Compton and his druggie daughter, Melissa. Then headlines and a stroke of casting genius set a different course.

First came the hardhat riots. Richard Rogin described the scene in the New York Times: “With cries of ‘Kill the Commie bastards,’ ‘Lindsay’s a Red,’ and ‘Love it or leave it,’ they surged up to City Hall. There they forced the flag, which had been lowered to half-staff in mourning for the four Kent State students, to be raised again. Then, provoked by peace banners, they stormed through Pace College across the street. It was a day that left New York shaken.”

Wexler and Avildsen rushed to revamp their film to sync with current events. Just as important, they realized they had struck gold with Boyle, a gifted comedic actor who could also turn on the menace. Boyle’s Joe, with his over-the-top vulgarity and dark, mischievous eyes, stole the movie, from the title on down. Sarandon later admitted as much: “They saw that they had a godsend in Peter Boyle and they re-edited it to emphasize him.”

Joe is initially drawn to Compton because the businessman has dared to do what Joe can only talk about: kill a hippie, or at least a junkie, in a scene that makes the most of psychedelic effects right out of drug exploitation movies like “The Trip.” But the businessman and the workingman find other reasons to envy each other as well. Joe is wowed by Compton’s salary (“The president of my union pays himself that kind of money!”). Later, Compton tells his wife that he envies Joe’s rough edges and directness: “I wouldn’t mind letting him sit in on one of our creative sessions, and let him tell everybody what a bunch of windbags they are.” And they both hate what those crazy youngsters are doing to the country. As Joe tells Compton during the film’s bloody climax, “You hate them as much as I do.”

Where the killers of the counterculture in “Easy Rider” were presented as redneck yokels, “Joe” gives us city-dwellers from opposite sides of the class divide. Before the film’s final carnage, Joe and Compton take a swing through the East Village in a quest to find Compton’s daughter. Shot on location, “Joe” takes us into the seedy New York that would reach its filmic apotheosis six years later in “Taxi Driver” (also about vigilantism, and also featuring Boyle in a smaller though pivotal role). At one point, Joe and Compton pop into a head shop to ask the proprietor if he has seen the missing girl. Joe gazes at a poster of a smiling Richard Nixon, emblazoned with the words, “Would you buy a used car from this man?” Joe is aghast. “Look at that,” he says. “The President of the United States. If you can’t buy a used car from him, who can you buy a used car from?” Together, the well-heeled Compton and the aggrieved Joe form the ideal snapshot of Nixon’s base. “After all,” as Geoff Pevere writes in the Toronto Star, “Joe was really a card-carrying member of Nixon’s cunningly designated primary constituency, that ‘silent majority’ of decent Americans—hardhats among them—who were fed up to here with all the craziness and liberal laxity corrupting their once great country.”

None of this prepares us for the film’s bloody denouement. Joe and Compton’s journey through the hippie underworld leads them to a group of druggies, who are happy to partake of the stash Compton stole after he beat the dealer to death. Joe and Compton, in turn, take part in an “or-gy” (Joe pronounces it with a hard “g”), indulging, as so many do, in that which they fear, loathe, and desire the most. Having tasted the forbidden fruit, Joe and Compton discover the druggies have stolen their wallets. With a selection of Joe’s guns in tow—“I got what you might call a well-balanced gun collection, see?”—Joe and Compton track the thieves to a country commune, where they massacre everyone. Unbeknownst to Compton, the final victim, who he shoots in the back, is his missing daughter, captured in a chilling freeze frame as she falls to the ground.

“Joe” became a cultural touchstone in the aftermath of its release, its resonance only enhanced by the hardhat riots. Boyle, a liberal improv actor just finding his place in the movie industry, recalled the reactions he received when he went out in public. He went to a 2 a.m. screening and found people “screaming at the screen.” The movie was a sort of Rorschach test for a bitterly divided public. Boyle was hailed—Hey, Joe!—as a long-lost buddy by New York hardhats, and profiled as a rising star in Life, where he confessed to be being horrified to overhear one middle-aged man explain “Joe” as “a movie about a guy like me who’s sick and tired of all this crap.” Meanwhile, the actor recalled, “Kids are standing up at the end of the movie and yelling, ‘I’m going to shoot back, Joe!’”

The brutal ending of “Joe” provoked comparison to the climax of “Bonnie and Clyde.” Both films keep viewers off balance with a mix of laughter and carnage. But it’s “Joe” that wields social satire with a serrated edge and tears open the era’s societal fissures. “For all its funny moments,” Mark Goodman wrote in Time, “‘Joe’ is anything but comedy. It is a film of Freudian anguish, biblical savagery and immense social and cinematic importance.”

What might Joe do today? It’s not hard to picture him trading in his hard hat for a MAGA cap and hauling out his well-balanced gun collection to stare down a Black Lives Matter protest. He might have trouble dragging Compton along, though Compton would still vote for the candidate offering the best tax cuts for the wealthy. The Nixon coalition, now the Trump coalition, is alive and well and preaching law and order and all lives matter. If anything, Trump speaks more directly to the Joes of the world than Nixon ever did. If today’s Joe had a computer, he’d be on Parler by now.

But it’s hard to imagine a contemporary film like “Joe,” or a studio that would be brave enough to release it. The times may be ripe for social satire, but the movies don’t much care. A full-throated, deceptively tragic dark comedy rooted in the most flammable social conflicts of today? Not yet, anyway. To watch “Joe” now is to revel in movie mischief unrepeatable, wrapped in political soothsaying that still stings.

“Joe” is now available on Amazon Prime.