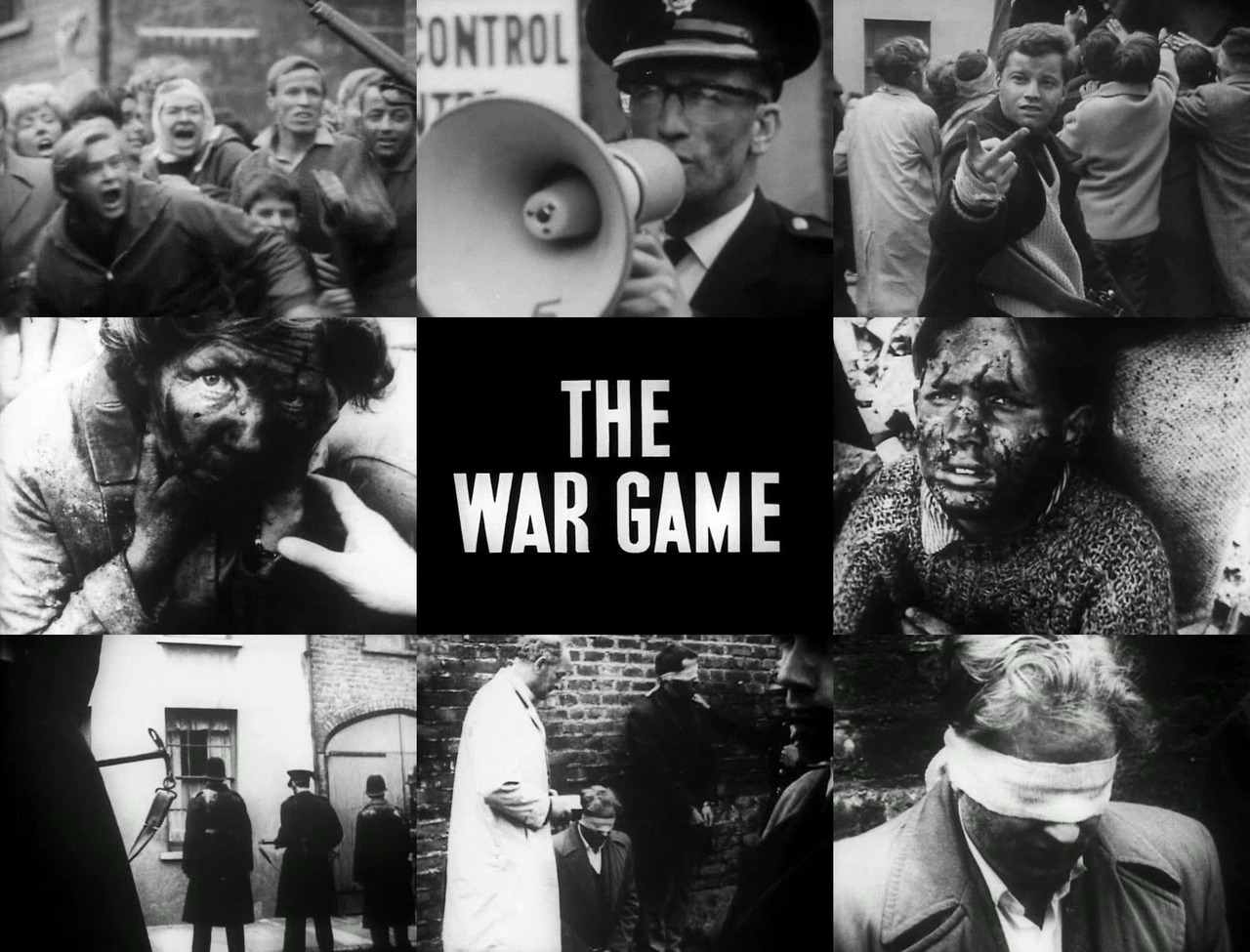

“The War Game” is one of the most terrifying films I have ever seen. Although it was made more than 50 years ago, its sobering presentation of nuclear war remains utterly gut-wrenching with many unforgettable moments of terror and despair. While the number of nuclear weapons around the world has considerably been decreased since the end of the Cold War, we are still living with thousands of them, and, unfortunately, that dreadful possibility of nuclear war becomes a lot more possible than before as our world becomes more volatile and unpredictable in recent years.

Thanks to its austere docudrama approach, the first half of the movie feels like watching an alternative timeline we were fortunate enough to avoid. As the Vietnam War becomes more intensified, China invades South Vietnam, and then the U.S. threatens to use nuclear weapons against China. After that point, the Soviet Union decides to blockade West Berlin for demonstrating its solidarity with China, and the US and its NATO allies in Western Europe come to attack East Germany for breaking off the blockade.

During the opening scene, the narrator calmly explains why Britain will be particularly vulnerable if this alarming situation is ever escalated to the stage of nuclear war. We see numerous dots on the map of Britain, which are the sites of many airfields and military bases where nuclear weapons are deployed. And then we see how these military sites are not so far from several dense areas where a third of the entire population of Britain reside.

As the situation gets worse in Europe, the British government and its officials begin to prepare for the worst. Thousands of citizens in London and other major cities in Britain are ordered to evacuate to rural areas as soon as possible. The guideline for possible nuclear attack is quickly distributed in public, and so are other important items including ration cards and identification cards.

However, it is apparent that neither the British government nor its citizens are prepared for what may happen, and the movie makes a sharp point on that aspect. Several different citizens are interviewed, and they all have no idea on how hazardous nuclear fallouts can be. We later meet a citizen who seems to be fully prepared with heaps of sandbags, but, as many of you know, his preparation will be useless if a nuclear bombing happens near his house. As the full-scale nuclear attack from Russia is imminent, the narrator informs us that there will be no more than 2.5 minutes left for the people in Britain even in the “best” situation, and we get the most ironic line in the film as the siren eventually goes off: “This could be the way the last two minutes of peace in Britain would look.”

The horror of nuclear war is soon unfolded in front of our eyes. We see people blinded by sudden flashes of nuclear bomb explosions, and the narrator phlegmatically describes how severely their eyes and skins are burned by those blinding flashes which are 30 times brighter than daylight. Not long after one family hurriedly hides into their house, the house is shaken up by the massive shockwave resulted from a couple of nuclear bombs, and the close-up shot of this terrified family is one of the scariest moments in the movie.

While it is implied that the situation could be a lot worse, the consequence of the nuclear attack is enormous to say the least, and the movie puts us into right into the situation as it focuses on what happens after three one-megaton nuclear warheads are detonated over the county of Kent. We see a huge firestorm engulfing buildings and streets, and we are told that the temperature of its center is no less than 800 ℉ (427 ℃). As the firestorm virtually burns everything in sight, it also generates a mighty wind of 100 miles (161 km) per hour, and we see many firemen and civil defense volunteers blown away by this powerful air current. Around the end of this hellish happening, a lethal amount of carbon dioxide, methane, and carbon monoxide are released into air, and we get another chilling moment in the film as people are asphyxiated to death one by one. Some of you may think the movie exaggerates, but the narrator reminds us that what we see is based on what happened after the bombing of Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo and Hiroshima.

In a local hospital, we see doctors and nurses who handle casualties brought to their hospital after the nuclear attack, and one exhausted doctor tells us that, due to the shortage of equipment and medicines, they have no choice but to divide the casualties into three categories. While the casualties of the first two categories may get the treatments they need, the ones in the last category, who are in terminal states, are simply placed in a “holding section,” where they are left to die without much help unless mercy killing is executed on them.

In the case of survivors without serious physical injury, they may look relatively fine in comparison, but most of them are traumatized by what they experienced during the nuclear attack, and there is no psychiatric help available. As we see them still suffering from their horrible experiences (one of them is barely able to eat a dish of soup given to him, for example), the narrator impassively observes: “This, too, will be the legacy of thermo-nuclear war.”

The situation looks a bit less grim a few days later, but the horror continues. One morose soldier tells an interviewer that there were so many dead bodies in buildings that they had no choice but to burn those bodies all together instead of burying them. We are told later that wedding rings were taken off bodies for identification, and we get a stark moment of emotional gut-punch when a guy shows us a bucketful of wedding rings.

Meanwhile, the society slowly begins to crumble with increasing chaos and anarchy. The shortage of food leads to a number of violent riots, and policemen are allowed to shoot civilians if that is necessary. An expert tells us about how decent ordinary middle-class people can develop the indifference toward the laws during and after war, and we soon see a textbook example from one housewife who pilfered several cans of food right after the attack on a Government Food Control center.

Around four months after the nuclear attack, Christmas comes, but nothing looks hopeful at all. During his Christmas mass, a pastor tries to make the mood a little brighter through music, but everyone remains silent and hopeless. We later meet a group of young orphans, who give us the most heartbreaking moment in the film when they are asked about what they want to be in the future. One of them says “I don’t want to be nothing,” and to our horror and sadness, everyone else gives the same reply one by one.

“The War Game” is written and directed by Peter Watkins, who did an astonishing job of depicting his subject with sheer authenticity and verisimilitude. Shot in rough black and white newsreel film, the movie often looks like genuine archival footage, and its shaky handheld camera further accentuates its frightening realism. In addition, Watkins often intercuts some of the most horrific moments in his film with faux interview clips of authority figures in favor of nuclear weapons, and you will roll your eyes as they make their outrageous statements in front of the camera (believe or not, these statements were based on genuine quotes).

Not so surprisingly, the movie generated controversy around the time when it was scheduled to be broadcast on TV in October 1965. Because it was clear that the movie was intended as a criticism against the nuclear weapon policy of the British government during that time, the BBC showed it to a group of senior government officials in advance, and then the film was banned from being broadcast because, according to the official statement from the BBC, it was judged to be “too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting”. Fortunately, because the ban only forbade television broadcast, the movie could be released in movie theaters instead, and it eventually won the Best Documentary Oscar in 1967 although it is technically not a documentary film. (After this rather odd case, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences changed their rules regarding eligibility for the category in question, by the way.)

After “The War Game,” the Cold War continued for 25 years, and it should be noted that there were a number of notable movies about nuclear war during the 1980s. “The Day After” (1983) surely shocked thousands of American TV viewers (and me later), but it has nothing on the eviscerating emotional power of the BBC TV film “Threads” (1984), which is probably the only movie on a par with “The War Game.” In case of theatrical films, “Miracle Mile” (1988) is still scary, and “Testament” (1983) does not lose any of its sad dramatic power thanks to Jane Alexander’s Oscar-nominated performance.

While the nightmarish situations imagined in “The War Game” and these terrifying films may belong to the past now, I must remind you that there are still 14,930 nuclear warheads around the world at present according to the Federation of American Scientists. In his 1967 review of “The War Game,” Roger Ebert said that the movie “should be shown to the leaders of the world’s nuclear powers, the men who have their fingers on the doomsday button.” Considering the current political situation around the world, I cannot possibly agree with him more.