What compels a man to descend into madness? At what point does he abandon reason to pursue the unspeakable? Man is never more dangerous than when blinded by his own rage. From such darkness emerge acts so brutal that they expose how fragile the boundary is between humanity and monstrosity. The criminal acts that follow become less a rational decision than an eruption of the unconscious. This idea of unconscious violence is at the heart of Toshio Matsumoto’s terrifying vision about the dark nature of humanity: “Shura,” aka “Demons.”

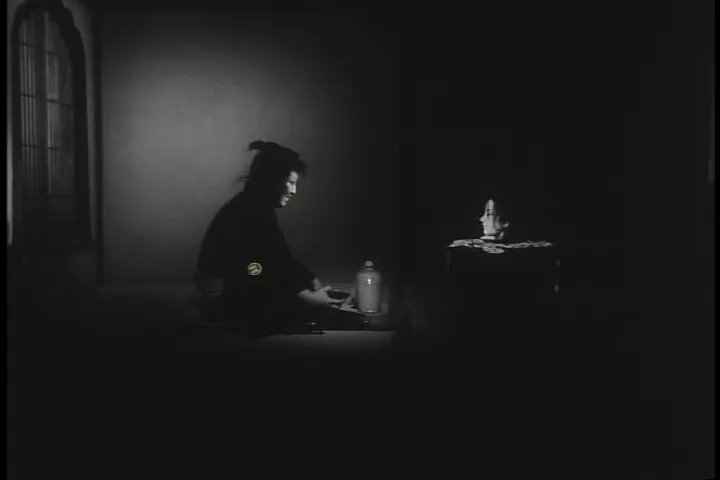

Gengobe is pursued at night by an unseen force through the village. As he’s running, he constantly glances back. We see variations of the same shot of him looking back over and over again. Each cut is a different take presented from a different angle. Lanterns drift toward him. Their carriers appear hidden in the shadows, as though the flames themselves are hunting him.

He breaks into a house in fear of being caught. As he gropes through the darkness, calling out for a woman called Koman, Gengobe’s foot strikes something. On the floor lies a severed hand. He looks up and sees a room filled with corpses. The corpses are scattered around an unconscious woman. It’s Koman. We see blood spilling from her mouth. He then sees himself suspended from a noose. The last trace of light is consumed by darkness. Gengobe wakes up. Out of the black, a face emerges. It’s the same woman who was butchered in his vision, only now she’s alive.

This is the opening sequence of a film known by many names (“Shura,” “Pandemonium,” “Bloodshed,” but most commonly as “Demons”), but rarely seen. This obscurity is quite surprising given that it was directed by the great experimental filmmaker Toshio Matsumoto. Matsumoto was a well-established film critic and theorist best known for adapting Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex into the queer masterpiece, “Funeral Parade of Roses”. But to me, his greatest avant-garde work is this one. “Demons”/“Shura” remains one of the most radical films ever made. Its daring techniques continue to astonish even today.

Toshio Matsumoto’s bleak samurai film follows a ronin in love with the courtesan Koman. When he learns that she’s about to be sold into a life she does not desire, he raises a huge sum to buy her freedom. He gives up all the gold he has. It isn’t long before we discover that this was all part of a scheme that she had been plotting with her husband all along. When Gengobe discovers the truth, the story spirals into bloodshed and tragedy. This descent into betrayal and violence is foreshadowed in the film’s opening image. The very first shot of the film is that of a round orb of the orange sun sinking low on the horizon. It is the only burst of color in the entire film. As it vanishes, the world is plunged into darkness, both literal and figurative. Any trace of color is extinguished. Despair seeps into the narrative with this shift to black-and-white.

Unlike Kurosawa’s samurai epics or Kobayashi’s moral tales of feudal cruelty, “Shura” refuses the possibility of dignity. Kurosawa’s heroes often fought for community. They sacrifice for the greater good in films like “Seven Samurai”. Kobayashi’s “Harakiri” unmasked the hypocrisy of samurai codes but still found nobility in rebellion. Matsumoto, by contrast, drains the samurai myth of every shred of romanticism. His ronin is not a protector, nor a rebel, but a man spiralling into disgrace. What we experience is the complete inversion of the bushido code. Here, we don’t witness honor in death, but dishonor spreading like a plague. If the genre often served to uphold ideals of loyalty, sacrifice, and justice, “Shura” dismantles them completely. Here, the only code left is betrayal.

The film’s title, “Shura,” refers to the Buddhist asura, which are demigods condemned to a realm of endless conflict. These demons are consumed by envy and aggression. In Japanese usage, the title also implies scenes of horrific bloodshed (shuraba), a battlefield of carnage where violence spirals beyond return. Matsumoto’s choice of title fuses these meanings. This idea of endless conflict shows up in the film’s form, trapping the viewer and characters alike in a cycle of hopelessness and violence.

The film utilizes jarring edits where gestures or movements are repeated across cuts. At first, these repetitions feel like an experimental flourish, as if the director is playing with rhythm and tempo. But soon this effect destabilizes the viewer’s sense of time. We start to see longer sequences being repeated. Only this time, the protagonist carries out entirely different paths or actions. Sometimes these repetitions appear as dreamlike fantasies, while other times they feel like speculative futures where the cycle of violence might be broken.

We begin to realize that we may be slipping in and out of subjective perception. The line between reality and fantasy becomes blurred. Time itself bends. Whenever something happens in the film, I found myself completely uncertain if it was actually happening or not, because Matsumoto had already established this disruptive threat of repetition. In other words, the film makes the viewer lose all sense of what is real in the very act of watching. We experience a complete collapse of certainty.

What is the true nature of man’s corruption? Who bears the weight of the unspeakable horrors humans unleash? The samurai’s blade may carve out justice for those who wronged him, yet in each stroke it engraves his own damnation deeper into his soul. In this world, vengeance feeds upon itself like a fire consuming all oxygen. The characters bid for freedom with small selfish acts that only deepen their ruin.

It was based on a kabuki play by Tsuruya Nanboku, a towering playwright of the Edo period. He was known for works steeped in the supernatural and the grotesque. Over his career, he wrote around 120 plays, often blending horror with the ghostly and uncanny. It came as no surprise that he was also the author of Yotsuya Kaidan, Japan’s most famous ghost story. Adapted into film more than 30 times, it shaped the iconic yurei image that influenced J-horror classics like “Ringu” and “Ju-On”. Yet nothing compares to the darkness of “Shura”. In “Shura,” what’s terrifying isn’t the supernatural, but a cruelty so boundless it defies reason.

There is one scene that remains among the most horrifying in all of cinema. Gengobe, consumed by rage and humiliation, approaches a crying infant. For a moment, we hope compassion might break through his madness. The baby’s face fills the frame. Then, the dark shadow of a blade slides across its face. The director cuts to a wider frame. The horror lies not in what is shown but in what is heard, or rather, what is no longer heard. The absence of the child’s cry screams louder than any image. It’s one of the most unnerving moments in all of cinema because it shows the precise point at which man’s fury erases the most sacred boundary of all, the protection of innocent life. This moment is horror distilled to its purest form.

In that instant, Matsumoto violates our senses and erases any possibility of redemption for our main character. What lingers is a horrific realization. Once revenge devours all rational thought, it annihilates the very foundation of human compassion. When I finished the film, it took days to shake it off. Its dark, nihilistic vision of humanity was overwhelming. It still stings half a century later because its vision of violence is not bound to samurai codes or Edo-period morality, but to cycles we continue to recognize in our own world. Violence erupts, retribution breeds retaliation, and the innocent are always the first casualties.

Watching the film now, as a new parent, its sound and imagery felt devastatingly heavy. The darkness born of what is shown and withheld, heard and silenced, was too much to bear. Matsumoto’s “Shura” shows how unchecked vengeance gives rise to unspeakable atrocities. Once violence crosses the threshold of innocent lives, it marks a line humanity must never cross. To repeat the cycle of violence is to extinguish empathy itself. To break it is the only way forward.