On Netflix Instant

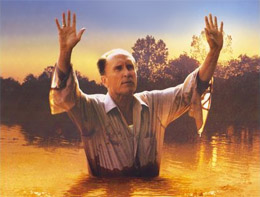

Robert Duvall‘s “The Apostle” (1997) is the story of a preacher who believes he has unique permission to phone call the Divine. As is the case with such preachers, the rules of goodness and morality seem to apply to everyone else before they apply to him. Meaning, he is above the law until he gets frightened for breaking the law. So, his combination of impious exhilaration, impatient devotion, and self-righteous rage reveals a man in sunglasses, open palms, and fiery sermons, who plants trees while burning bridges. I love this movie as much as I despise its central character. This movie exists only because of its central character.

The whole story, in a nutshell: Robert Duvall (producing, directing, writing, and acting) is the tunnel-visioned Apostle E. F. who runs a Texas church, but discovers his mostly abandoned wife (Farah Fawcett) has been having an affair with the Youth Minister. After a moment of intense vindictive violence, he goes on the run. He preaches along the way, subsequently arriving in a small town in Louisiana. He renovates a small church, becomes a local star for a few dozen parishioners, and fills the rows. Then, in a fitting spin of Deus Ex Machina, the police find him and arrest him, though he continues preaching. It is a very simple story with mostly one and two-dimensional characters, yet is one of the most vivid films I have seen.

I like wrestling with this film. The first time I saw it, I didn’t believe that the film’s Apostle E. F. believed a word he said. Watching it again, 15 years and over a thousand of my own lectures, classes, and sermons later, I still think the same about him, with one change: he believes that he believes every bit of his preaching, and that is all that matters. He reminds me of so many preachers I’ve met, like the man who preaches with force about women’s rights, especially out of concern for his daughter, but does not see the obvious inconsistency in his long string of solicitation of prostitutes. I don’t know how many times he’s been in jail, but he continues preaching. Or, the preacher who travels around the country for purposes of marital counseling, by claiming that the spouses are possessed by evil spirits (that only he is able to detect and remove), somehow getting caught in bed with the wives.

Then, there is the preacher who I seem to run into more often than I’d like, who speaks so forcefully against America’s apparently absent morality, absent because America apparently does not follow his version of his religion. Absent, especially because America is taking its women out of their homes, making them work. Apparently, it is also America’s fault that for the past few decades, he has remained mostly unemployed, living off of his wife’s wages.

Common among all of these charlatans is that they all know their respective scriptures, at least in content, thoroughly. But, deeper, they see themselves as victims. The above three keep commenting that they are victims of the Devil, victims of their own flesh, victims of their wives, or victims of the American system. In their minds, they are devotees of the Divine, yet are victimized by the world’s demons. As victims, they justify crossing boundaries of morality and law, and further support their behavior by random citations from scripture, thus giving apparently Divine sanction to their periodic inhumanities.

Another greatness of Duvall’s film, however, is that the film itself passes no such judgment on him, in contrast to “Kundun” and “Malcolm X,” where the filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee clearly admire the central characters. Here, the filmmaker seems to be busy chasing after the character. There is plenty to love and hate about the Apostle E.F., but the film does not spend time telling you which to choose. The film, however, aims to keep up with him as he races from pious scheme to scheme. In each scene, we seem to be just a half step behind him, and that technique alone keeps us guessing and glued. The film’s final moment seems to illustrate that the movie would run out of breath long before the preacher would. From start to finish, I doubt that you will love the Apostle E. F., and you might hate him. Considering the role his mother (June Carter Cash) seems to play in forming him and then enabling him, you might even sympathize with him. In any case, you will feel compelled to keep watching him.

This film also scares me. Aside from teaching religion in the university as a dispassionate academic discipline, I am frequently called upon to give sermons, classes, and pastoral care. I love the work as much as I love thinking about movies, if that makes any sense. But, I deeply fear becoming this man. He is neither the dreaming hypocrite J. R. from Scorsese’s “Who’s That Knocking at my Door,” or the ice cold Reverend Doctor Purify from Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever.” Those characters also keep our attention, but the Apostle E. F. is something more subtle; I find him repulsive in his style of self-perpetuating piety.

Further, he embodies a true religious violence: his conduct illustrates that he has fallen into the very simple traps that so many preachers have fallen into, where even the deadly sins can be justified as acts of piety. When we speak of religious violence, we often speak of war and bloodshed; that violence, however, is often caused by tribalism and nationalism as much as religious preaching. True religious violence is that violence which twists the innate goodness of the ordinary human experience into something deviant, justifying the process through scriptural sources. The true violence of religion is that which fools the believer into think that he or she is elevating when in fact he or she is getting subjugated into arbitrary postures. Thus this film reminds me that a preacher is either honest with him or herself, or he/she is not; there is nothing in between. Is the Apostle E. F. honest with himself? I don’t think he is; I don’t think he is capable of being honest with himself. But, I think he believes that he is and that is just frightening.

On the flip-side, the world he inhabits is a world of small town congeniality. All the other characters in this story, even with their own impieties, are deeply friendly. Most of the characters breathe at least some air of belief. But, they aren’t stupid: most of the characters know that some preachers are devils in the garb of angels, while others wash their feet with the waters of true devotion. But, all the characters in the film seem willing to give strangers some space to demonstrate their honesty. It is too easy to paint such characters as naïve simpletons, as so many films do. In “The Apostle,” however, the characters are simply friendly people in a friendly world.

In some ways, that is a caricature of the South. The Hollywood version of the American South seems to usually be a non-urban land of welcoming small towns, friendly simpletons, Pentecostals, Pickup Trucks, drunks, and/or racists. In contrast, the Hollywood version of the American North is often urban, complicated, corrupt and noisy. But, the characterizations in this film seem to illustrate a bit more than that. The film does not take us into the mind of the Apostle E. F., but it does show us the world as he sees it. As soon as each character appears on screen, you feel you already know everything you need to know. But, some of the characters are indeed welcoming, some are simpletons, some are drunks, some are racists. But, all are potential sheep for his flock. He does not need to know any other dimensions of their own stories. He knows his simple truth: that he can save them, if only they nod in approval.

![]()

The scenes themselves are often also caricatures. Near the end, we watch two scenes that are, on their own, completely heavy-handed and preposterous, yet are perfect in the film. In one scene, a man (Billy Bob Thornton) drives up on his bulldozer to take down the church, but gets blocked by the Apostle’s Bible, while the local radio station host whispers a play-by-play. In another scene, the police arrive to arrest the Apostle, yet they stand and watch as he manages to continue his sermon all the way to completion. That scene goes on and on, and we keep expecting either the cops to interrupt him, or for him to interrupt himself, but neither happens. Rather, he continues preaching, knowing that the Angel of Death has arrived, but he refuses to budge until he is ready to go.

And what do we make of the moment he gets discovered, as a result of a problem in a distant radio broadcast? Is Divinity a character in the story? If anything, even the smoothest talking pious fraud cannot escape the greater boundaries of justice, I suppose.

If the film raises any other question, it raises the question about the role of the preacher in the life of the parishioner. Whether or not the Apostle E. F. is a fraud, seems to be irrelevant. It is more important that he proves that he is human, for when we preach of fire and brimstone, we each might have a few scars from the heat. But, once the preacher establishes his “authenticity,” he can fish for followers all he wants. And, once they are in their pews, they know what to do for themselves; he is just the blazing Master of Ceremonies. As an approach to religion, there are many obvious flaws here, but it illustrates that for many people, doctrine is less important than efficacy. And if the preacher can facilitate that efficacy, then the flock will get on their knees for him. If he cannot, then they will join the Youth Minister.