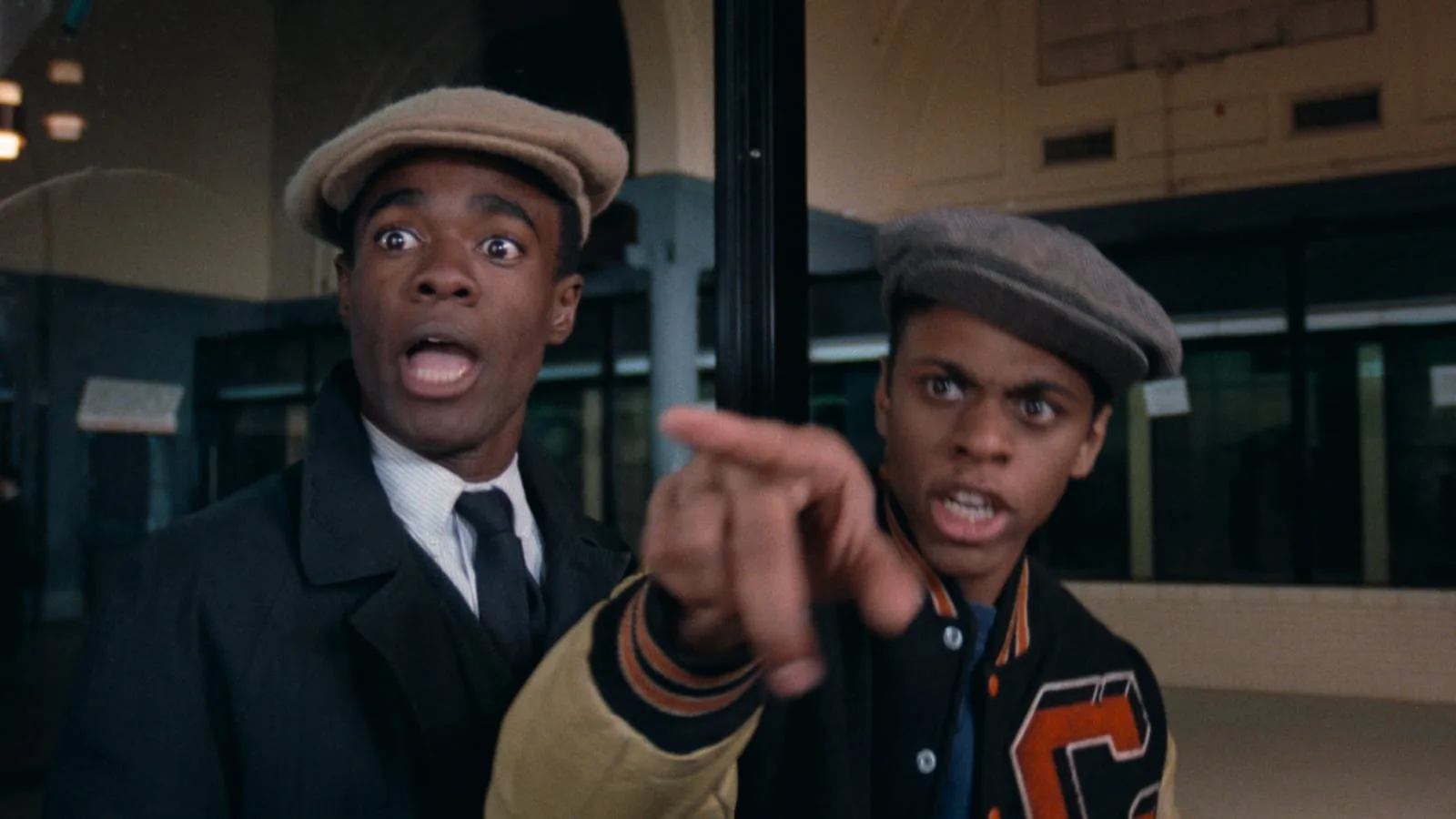

“Cooley High” opened at two theaters in Manhattan on June 25, 1975, less than a week after “Jaws.” Both theaters, the Cinerama in Times Square, and the RKO Twin on 86th Street, were known for showing Blaxploitation movies. Whether Michael Schultz’s classic dramedy can be classified as a Blaxploitation movie is debatable, but my answer is “well, yes and no.”

On that same day, “Cornbread, Earl and Me,” another film about Black teenagers that may or may not qualify as Blaxploitation, opened in the NYC area, including at the Stanley Theater in my hometown of Jersey City. This heartbreaking drama was the debut of a young actor named Laurence Fishburne III (as he is credited). You may know him for such roles as Morpheus in “The Matrix,” and that misplaced Black kid on the boat in “Apocalypse Now.”

Both “Cornbread” and “Cooley” are inextricably tied together in my memory because, as I mentioned in my review of “All Things Must Pass: The Rise and Fall of Tower Records” here on this very site, I saw both films on a double feature at the Pix Theater. That was our second run theater. It was one of the saddest afternoons I ever spent in a grindhouse.

I’d like to think that the late John Singleton, who was only 2 years older than I am, also saw this double feature in South Central at some point. Though I can’t prove by any measure that he did, you can find these two movies stitched into the DNA of his masterpiece, “Boyz N The Hood.”

Furious Styles himself is on record saying “Boyz” was directly influenced by “Cornbread,” and I agree, but the mise-en-scene of Singleton’s classic feels so much like “Cooley High” that the film almost plays like a remake. The beats and pauses, the broad comedy, and the total immersion into the neighborhood feel like a loving homage to Schultz’s film.

Not to mention the tragic event that shatters both films into bittersweet shards that pierce the viewer’s heart. “Boyz” had Ricky (Morris Chestnut) and “Cooley” had Cochise (Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs), two sports heroes whose almost guaranteed escape from the ‘hood was usurped by a needless death.

Through the movie screen, I got to know Singleton’s South Central the same way “Cooley High” informed me of the Chicago Near North Side neighborhood of screenwriter Eric Monte’s memories. They felt lived in, and as familiar as The Hill, the hood that shaped me and made me who I am.

Cuba Gooding Jr.’s Tre Styles has a few things in common with “Cooley High” protagonist Preach, played by a then 28-year old Glynn Turman. Like me, these were both sensitive souls who played tough or acted silly as defense mechanisms against the harsher elements of their existences. Preach was a poet and wannabe writer, a character I met at the same time I had decided that I, too, wanted to be a writer.

All these coincidences tie together in my mind and in my soul. I was going to write that “Boyz N The Hood” was my generation’s “Cooley High.” Truth be told, my generation’s “Cooley High” IS “Cooley High.”

You want proof? My eighth grade graduation ceremony featured my classmates and I singing the film’s original song, “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye to Yesterday,” 10 years before Boys II Men put out “Cooleyhighharmony.”

When “Cooley High” opened (it premiered at the Chicago Theater, by the way), critics referred to it as “the Black ‘American Graffiti’.” George Lucas’ Oscar-nominated memory piece opened two years prior, and like Monte’s screenplay, it was a semi-autobiographical look at the filmmaker’s adolescence. Both films end with onscreen explanations of the fates of their surviving characters.

They were also built wall-to-wall with music of the era. Set in 1964, two years after Lucas’ film, “Cooley High” was stacked with Motown classics, mostly from the Holland-Dozier-Holland canon. I can’t imagine how much money the rights to these songs would cost today, but in 1975, the price barely made a dent in the $900,000 budget from American-International Pictures.

“Nobody cared about these songs but us,” Schultz said during a Q&A at the TCM Film Festival.

What critics failed to notice with their lazy “it’s a Black [fill in the blank with White movie title]” cliché was that, unlike “Cooley High,” “American Graffiti” had loads of precedent. There were countless movies made before 1973 that focused on White teenagers, from “Rebel Without A Cause” to “The Blackboard Jungle,” which at least had 27-year old Sidney Poitier as a teen.

Numerous studio films focused on the childhood memories of their White protagonists. Hell, White kids even got to be teenage werewolves and boogie with Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello on the beach.

By comparison, films focusing on Black teenagers or the memories of Black protagonists were practically non-existent at the time of “Cooley High.” There was no “Black Beach Blanket Bingo” or “Rebel Without a Colored Cause.” And we damn sure weren’t turning into lustful adolescent beasts.

In fact, the first movie I can think of that put a Black protagonist’s memories on screen with the fervor of a White film’s reminiscences is “The Learning Tree,” the 1969 Gordon Parks movie that broke the directorial color barrier in Hollywood. We can also throw in “Sounder” and the early scenes of “Lady Sings the Blues.”

Besides the obvious racism and lack of imagination on Hollywood’s part contributing to this deficit of Black-themed remembrances, another reason why “Cooley High” seemed so fresh and important as a memory piece is its successful merging of all aspects of Black life, that is, the joy and the trauma. Far too many films focus on the latter, even to this day.

There’s a careful calibration of the two in “Cooley High.” Schultz, Monte and the cast give the film the laid-back texture that lazy days had when you were a teenager. Preach and his crew play hooky and go to the Lincoln Park Zoo where, in the film’s funniest scene, one of the guys is pelted with monkey poop. The poor guy will never live this down—he’ll be reminded of it at high school reunions and cookouts until time immemorial. How identifiable is that?

Even more identifiable is the scene that I’ve carried with me for decades. Garrett Morris’s teacher, Mr. Mason, confronts Preach about his goofing around. Morris, who made this film just before becoming one of “Saturday Night Live”’s original cast members, is very convincing in his teacher role because, before he was cast, he was teaching kids at PS 71 on Avenue A and Sixth Street of Manhattan’s East Village. And yet, the studio didn’t think he’d make a credible teacher, because they wanted a “Sidney Poitier type.”

“I haven’t seen one Sidney type teaching a class yet,” Schultz added when Morris told this story at a screening. A real life “To Sir, With Love” scenario would definitely get the kids to pay attention.

But I digress. Mr. Mason asks Preach a very pressing question: “What do you want? Don’t you want something?” If you’ve seen this movie, you know Preach’s immortal reply:

“I wanna live forever!”

Every teenager thinks they’re going to live forever. The older I get, the more I realize how ridiculous it was for my fearless younger self to think that would be possible. But Turman delivers that line as memorably as he wore the amazing, possessed conk he sported in “J.D.’s Revenge” one year later.

“Preach went to Hollywood and did become a successful screenwriter,” reads the description of his fate at the end of “Cooley High.” So did Eric Monte. He got this movie made, not to mention that he also created “Good Times,” invented George and Weezy Jefferson, and advised on this film’s TV counterpart, “What’s Happening?!!”

Preach may not live forever, but “Cooley High” most certainly will.