With the possible exception of the 1953 film “I Confess,” Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 title “The Wrong Man” is the least fun, or “fun,” movie of the master of suspense’s long and incredibly fruitful Hollywood period. Yes, earlier pictures like “Rope” and later pictures such as “Psycho” and “The Birds” went into realms of nearly irremediable darkness but even those pictures had their moments of humor, their inside jokes. For “The Wrong Man,” Hitchcock took his task so sufficiently seriously that he denied himself his usual winking cameo, the appearance (usually early on) of Hitch in some dryly humorous posture interacting with the world he’s creating. The director does appear in the movie, addressing the audience directly in a prologue, but his mien is different than it would be in his droll introductions to the episodes of TV’s “Alfred Hitchcock Presents;” presented in silhouette and long shot, he all but warns his audience that this is a “different” kind of story for him. The difference, we are meant to infer, is in the documentary value: the scenario is based on a true event, and Hitchcock tells it with great attention to realism and verisimilitude (there is a distinction between the two, one that Hitchcock appreciated). But anyone expecting, as a result, a movie devoid of expressive cinematic style, will be pleasantly surprised: this is as fluently styled a movie as Hitchcock ever made.

The movie tells the story of Christopher Balestrero, nicknamed “Manny,” a member of the house band at New York’s swanky Stork Club in the early ‘50s, who found himself on the receiving end of a very bad case of mistaken identity, enduring arrest and trial for a series of small-time robberies that he did not commit. Screen icon of integrity Henry Fonda plays Manny and Vera Miles is his wife Rose, who suffers a breakdown and serious attendant depression as a result of the ordeal. Despite his show-biz job, Manny’s a working class guy, stressed about money, making fantasy bets on horses on his subway ride home, flummoxed by his wife’s worry over having to come up with the money for some emergency dental work. Manny comes up with the bright idea of borrowing off an insurance policy, and in that office—located in both real life and the film in a Queens building called the Victor Moore Arcade, and yes, it was named after the famed comic actor—he is “recognized” by several tellers as a man who held them up that prior December. And so the nightmare begins.

Hitchcock’s crucial style is evident right from the opening credits. Over the credits, there’s a shot of the hopping Stork Club; the largely unseen band plays a lively tune as the camera pans left, and settles on one static view. Then, in a series of very unobtrusive dissolves, the nightclub crowd thins out. The jazzy music, composed by Bernard Herrmann, grows softer, less energetic; by the time we get to the director’s credit, it’s nearly closing time. As Manny walks out of the Stork Club and to the subway, he passes two beat cops, and as the camera follows, a composition resolves itself of the two cops flanking Manny, like, perhaps, protective angels watching over him as he descends to meet his train. From that moment on, though, the police are presented as surly, near-malevolent representatives of a system that wants to place Manny in captivity. (The lead detective in Manny’s case is played by a gruff Harold J. Stone, but the movie’s secret weapon, performer-wise, is Charles Cooper, investing the junior detective with a constant oily smirk that makes him read as an out-and-out villain.)

Writing about the film in June of 1957, future director Jean-Luc Godard—in a piece that stands as one of his very best, and most prescient, works of criticism—noted that “Hitchcock has never used an unnecessary shot. Even the most anodyne of them invariably serve the plot, which they enrich rather as the ‘touch’ beloved of the Impressionists enriched their paintings.” Similarly, in their 1957 book on Hitchcock in which they all but proclaimed “The Wrong Man” the director’s supreme masterpiece, future directors Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol upped that ante by proclaiming, “In Hitchcock’s work form does not embellish content, it creates it.” This is evident throughout “The Wrong Man” in a series of what Godard called “doubled scenes.” The two most obvious ones are the heart-to-heart talks between Manny and Rose in their bedroom. In the first, Hitchcock works around Production Code and Joe Breen censorship restrictions by having Manny sit on Rose’s bed; he leans in to her and holds her as they speak; the two are seen united in the frame, each in profile, as if on the verge of a kiss even as they discuss trying matters like how they’re going to pay to have Rose’s impacted tooth fixed.

In the second scene, after Manny’s arrest and release on bail, and as Rose is beginning to crack, they are depicted sitting a good deal apart from each other, and the shot-reverse-shot pattern of their exchange, along with the long shadows, creates the palpable impression of parties opposed to each other. Given how warmly the couple had been heretofore depicted, it’s heartbreaking.

The depictions of Manny’s jailing are equally vivid. With the possible exception of a by-now anachronistic tilt-a-whirl camera effect to suggest Manny’s dizziness in his jail cell, this material is handled as impeccably and dynamically as Bresson did in his film “A Man Escaped,” also from 1956. Does a jail cell look different to an innocent man than it does to a guilty man? It’s an interesting question; in both these films the protagonists are free of sin, so to speak, but they are also seeing the inside of a cell for the first time. Godard says that when Manny enters the cell for the first time, he is “seeing without looking,” and that the protagonist of the Bresson film “does the exact opposite”—because, and this difference is crucial, Bresson’s hero has the intention of getting out of there. Manny can see no way out, and the condition of confinement, from the dingy walls of the cells to the dead-click sound of the handcuffs, is rendered with a terrifying attention to detail. Remember that Hitchcock had a lifelong fear of the police, stemming from when his disciplinarian father once took him down to a precinct house on an occasion that the then-boy had misbehaved. Black-and-white has maybe never looked more black and white than in the scene in which Manny sits handcuffed in a traveling police van.

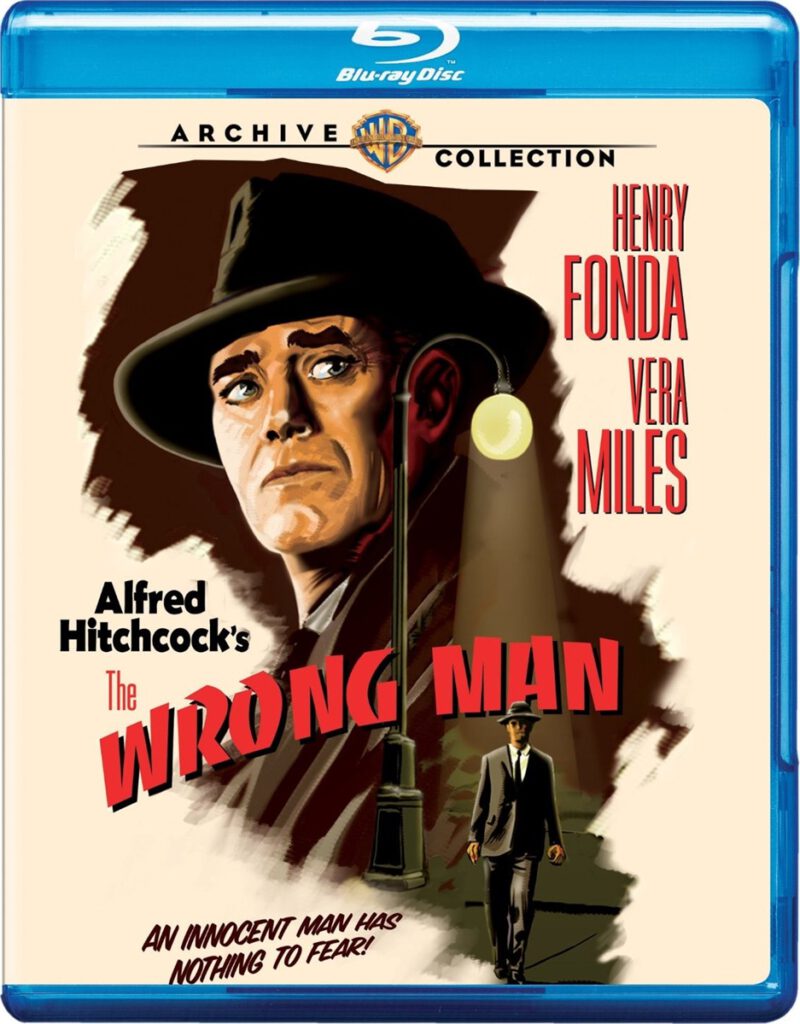

Which brings me to the reason I’m now offering these notes of appreciation: a new Blu-ray disc of the movie, just released by the Warner Archive. It is a truly splendid high-def rendition of the film in a 1.77 aspect ratio very close to its theatrical presentation, taken from superior materials. There’s a show of noticeable grain in certain scenes but for the most part the texture is extremely solid; the visuals are striking, compelling. (The screen caps illustrating the Manny and Rose scenes are taken from the standard-def edition; directly above is a screen cap from the DVD Beaver review of the disc, for contrast.) In every other respect it matches the 2004 edition, but the Blu-ray boost is appreciable, and makes this movie, one of Hitchcock’s most dread-filled but also one of his most compassionate (not to mention Catholic), an exemplary home-theater-library item.