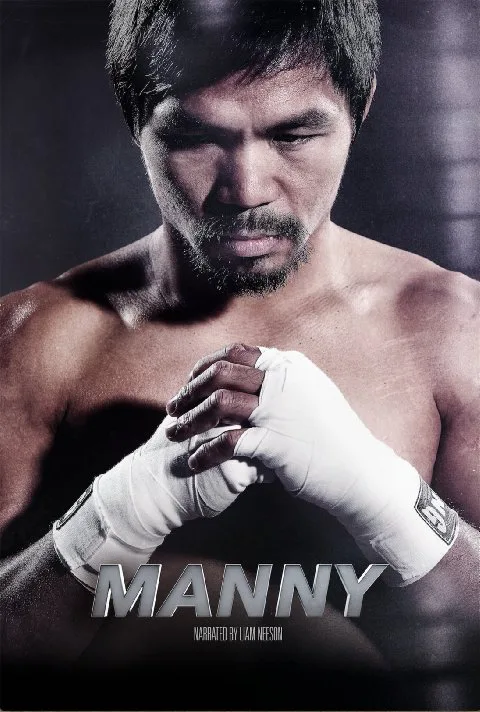

Having already accomplished enough in the ring to earn comparisons to such legendary champions as Muhammad Ali and Mike Tyson, Manny Pacquiao now clearly hopes to equal their achievements in the multiplex with the new documentary “Manny.” In the history of boxer documentaries, “The Trials of Muhammed Ali” (2013) and “Tyson” (2009) were spellbinding overviews at the respective careers of those controversial fighters; “When We Were Kings” (1996) took viewers behind the scenes of the classic 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” between Ali and George Foreman, and was simply one of the great sports documentaries of all time. Pacquiao’s shot at cinematic glory winds up missing the mark. Despite having a life story seemingly tailor-made for the big screen, it transforms his potentially fascinating tale into a narrow and borderline fawning hagiography that will no doubt find great favor among his fan base, while inspiring shrugs of indifference from those less invested in his tale.

Born in 1978 in the war-torn Philippines, Pacquiao lived in great poverty and was essentially supporting his entire family by the age of 12. After his family moved in with his uncle, he began to learn the art of boxing and proved to be adept at it despite his short stature and skinny frame. Before long, he left for Manila (living in the gym where he trained) and once he turned pro at the age of 16 (though he claimed to be 18 in order to get his license), he began to regularly win bouts there as well and eventually decided to seek fame and fortune in America. Within days of his arrival, he would find a trainer in former boxer Freddie Roach and win his first fight despite having less than two weeks to train and 44-1 odds against him.

He would continue to win big bouts over the likes of such noted fighters as Oscar de la Hoya and over the years, he would pull off the unprecedented feat of winning world championships in eight different divisions—a move that would make him an enormously popular athlete throughout the world and a national hero in the Philippines. Over the years, his success and celebrity would lead down some familiar paths, such as making a fortune even as his advisors wound up taking much of the money for themselves. There would also be unexpected detours, such as his secondary career as a star in the Filipino action film industry (including his work as superhero Wapak Man and yes, there are clips) and a decision to run for congressman back home while still maintaining his other career. Then there are the things that simply defy description, such as a love for schmaltzy love songs that at one point finds him teaming up with composer Dan Hill to perform a cover of “Sometimes When We Touch,” and at another has him on Jimmy Kimmel singing “Imagine” with Will Ferrell.

This is all superficially interesting, I suppose, and the undeniable charisma of Pacquiao does help it all go down easily enough, but, in the end, I wanted more than “Manny” was willing to give. There is much talk about how he is one of the great fighters of all time but there is never any point in which the film breaks down in any detail what it is that separates him from other fighters. There are plenty of clips of his greatest hits but without any sense of context, they fail to make the case that boxing is just as much about skill as it is brute force. Take a film like the aforementioned “When We Were Kings”—it took the time to illustrate what was going on in that bout that allowed Ali to triumph over the odds through illuminating commentary by the likes of Norman Mailer, a guy who did know his stuff about the sport. Here, we get starstruck commentary from the likes of Mark Wahlberg and Jeremy Piven and let me just be the first to say that whatever his qualities, Jeremy Piven is no Norman Mailer. (The lack of depth in this regard is even more surprising considering that it was co-directed by Leon Gast, who directed “When We Were Kings.”)

Another big problem with “Manny” is that it seems way too circumspect in its depiction of Pacquiao. We never get any real sense of his life outside of the ring—his wife, Jinkee, is introduced in the most offhand manner imaginable, and if his children are cited by name, I missed it. There are brief suggestions of his misbehavior outside of the ring involving booze, gambling and women that the film is unwilling to delve into in any significant manner, though it does allow him a speech at the end where he praises himself for forsaking such temptations for good. As for his political career, we get one brief comment from a rival, but, again, it refuses to probe into the accusations that Pacquiao has failed to balance his two careers, to the detriment of his constituents, in any detail. In such details, the film is so bland and toothless that the whole thing could have put together by his own reelection committee.

Of course, none of this will matter much to hardcore fans of boxing in general and Pacquiao in particular—they should probably mentally add another star to the rating above. However, anyone looking for a penetrating and incisive examination of the Pacquiao phenomenon will have to keep searching, because “Manny” is not it. Funny how a film about a man who became famous for not pulling any punches could be accused of doing just that.