Videogame culture looks bad.

Several of the most-publicized, least-deserved attacks against women on the Internet have been game-related. Anita Sarkeesian, creator of the Feminist Frequency videos analyzing portrayals of women in pop culture, was the highest-profile target. She had the gall to crowdfund the series’ shift in focus to video games, and for that has been punished by a nasty cybermob, treating her as the enemy of all games.

More recently, game critic Carolyn Petit presented the video review for Grand Theft Auto V at Gamespot, and despite talking about how much she enjoyed the game in general and scoring it a 9/10, she became a target of the Internet’s violent expressions of ire for making a brief set of complaints about the game’s treatment of women. The founders of the Penny Arcade Expo, the massively successful by-gamers-for-gamers convention, have their own, quite public controversies.

There’s certainly enough disgusting stuff happening related to games that repudiating the whole damn culture seems appropriate. A recent example of this was published at Errant Signal, the blog of game developer Chris Franklin: “It’s rash and emotional. It’s often hateful. It doesn’t care who it hurts. This is the gamer subculture I rail against.” Franklin’s motives are good, and his targets are deserving of opprobrium in the piece.

But by framing it as a “gamer culture,” Franklin and the many other people who’ve written this type of blog post do a disservice to their arguments.

For one thing, they provide a narrow view of “gamer culture,” one which seems to surrender the very idea of games and gamers to the worst impulses of the community.

Are the people who donated $158,000 to Sarkeesian, more than twenty times what she asked for, not part of video gamer culture? Am I, a critic who includes social justice analysis in my discussion of video games, not part of the culture? Perhaps I’d feel better if there was some other term that I could flee to, but then I realize how hard I’d roll my eyes if someone told me that he or she were engaged in “film culture, not movies.”

Why are the best-intentioned members of the subculture so willing to reject “gamer culture” in its entirety, treating it as though it’s uniquely bad?

By framing these virulent cybermobs as an issue of “gamer culture” instead of connecting it to culture at large, these anti-gamer pieces miss the forest for the trees.

The use of the word “gamer” also gives the impression that there’s something innate to video games or gamers that triggers this rabid response.

And there isn’t.

These disturbing reactions are not confined to the world of videogames.

They’re everywhere.

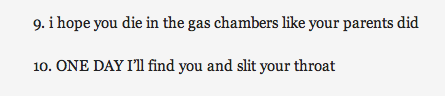

Violent backlash against critics who engage in criticism is easy to find in the film world. The anti-critic (or anti-intellectual) impulse was plain to see last summer, when movie critic Marshall Fine received Internet hate and death threats for daring to pan “The Dark Knight Rises.”

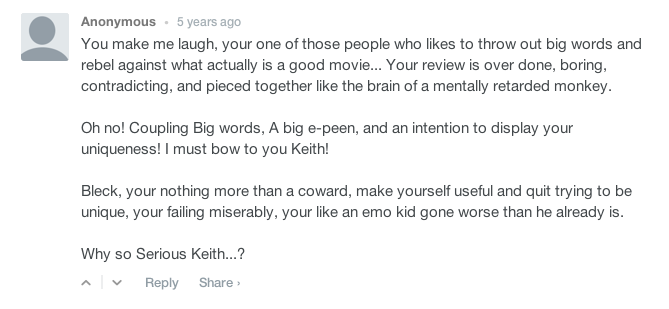

The House Next Door‘s Keith Uhlich was attacked with similar viciousness four years earlier, for the same perceived sins, when he panned “The Dark Knight.”

The video game website Kotaku recently noted the similarities between the violent sentiments expressed by fans of the Call Of Duty military shooting video games to those sent to GQ by angry fans of the clean-cut boy band One Direction.

The word “fan” is usually to describe anyone with a particularly specific enjoyment of, well, anything, and it’s usually done in positive or at least neutral tones. That makes it easy to forget that the term is derived from “fanatic”—meaning one whose adherence to religious dogma renders them incapable of critical thought, and sometimes inclined toward violence.

Many of these examples fit within the framing of product-as-religion. The Call Of Duty threats, for example, came to the PR guy who announced changes in multiplayer game balance—i.e., altering the game’s bible by strengthening some weapons and weakening others.

Yet even religious fervor is insufficient to explain how game culture controversies relate to the wider world. After all, most of these situations aren’t simply cases of gamers behaving badly. They’re very specifically oriented, targeting primarily women or trans people. These are issues of sexism, not issues of video games.

A parallel example: a year or two ago, at the height of the anti-bullying fad, I read a cogent article about how “bullying,” when detached from larger issues of social justice, became meaningless. Most bullying fits within existing issues—boys bullied for not being masculine enough, girls for not being feminine enough, race, sexuality, body size, and so on and so on, all relate to wider societal issues.

Making rules against specific acts of bullying was insufficient if the culture at large still agreed with all the reasons for the bullying. The culture agrees with what Chris Franklin’s definition of “gamer culture” believes.

It’s not just sexism, either. This past Sunday, longtime sportscaster Bob Costas used his time on Sunday Night Football to criticize the Washington football team’s use of the ethnic slur “Redskins” as a nickname, to predictable backlash.

One of the most common criticisms was that Costas should “keep politics out of sports.” Franklin’s post discussed the same sentiment with regard to games. “Politics,” according to this narrow view, essentially means “caring about anyone who’s not a member of the dominant groups of society.” Or, as political writer Jamelle Bouie put it, “The anger at Bob Costas re: the Redskins is a reminder of how angry people get when you challenge any privilege, regardless of how trivial.”

Just being asked to care about less well-represented people causes large groups of people to express abhorrent sentiments.

A huge contingent of Breaking Bad fans identified so strongly with the series’ anti-hero/villain protagonist, Walter White, that they framed the entire show as the tale of a henpecked genius pulling heroically away from the shrewish claws of his wife, Skyler—a notion they expressed via monumentally sexist diatribes.

Lauren Mayberry, the singer of the rising band CHVRCHES, recently described what it was like to be a woman who was a public figure, including some of the more vile quotes that men had sent her—especially after she’d mentioned receiving harassment.

Jezebel’s outspoken writer and comedian, Lindy West, wrote in June about the aggressive response she received after attempting to discuss rape jokes on television. The piece’s title (“If Comedy Has No Lady Problem, Why Am I Getting So Many Rape Threats?”) makes the point clear, although there are dozens of examples in the text to hammer it home.

The hate isn’t just confined to Twitter streams and comments sections. It’s increasingly common in politics.

In the 2012 American election, a significant chunk of one of the two major parties devoted itself to attacking women. Rush Limbaugh, PR arm of the Republican party, cast grad student Sandra Fluke as a Democratic slut-demon for the crime of publicly asking that women’s health be included in her health care package. Bashing Fluke has become a pastime for “family values” types—just a few days ago Gary Bauer made attacking her a key part of his speech at the “Values Voter Summit.”

When the dominant culture is threatened, it responds with vile and violent rhetoric, attacking all who dare question it.

That rhetoric is not always idle. Two recent stories demonstrate the willingness of communities to turn against any threat to the comforts of their powerful. In both Steubenville, Ohio and Maryville, Missouri, teenaged girls accused football stars of rape, and they, their families, and their defenders were anonymously and publicly vilified for it—in Maryville, the girl’s house was burned down.

There are a lot of different terms for the culture that the virulent mobs defend: the privileged, the dominant, the elites, the comfortable, and so on. And it’s usually, but not always, related to those common points of analysis: gender, race, class, body size, and sexuality.

But the pattern is consistent: a subset of the dominant group responds with irrational violence and cruelty to any perceived threat.

When the mob attack happens in relation to video games it can appear more notable, because games are rarely discussed with nuance in mass media, and gamers are really good at using the Internet (games and porn built the mass Internet, after all, and pornographers see much more value in being quiet).

Thus it’s not “game culture” or “sports culture” or “political culture” or “music culture” or “comedy culture” or “film culture.” It’s simply culture.

The worst aspects of American, or Western culture will rise up when the comforts of the status quo are scratched or dented in even the mildest of fashions.

Attempting to damn one subculture without acknowledging where that subculture intersects with others, and with culture at large, will always be insufficient and misleading.

That’s why I’m not willing to cede the entire concept of “gamer” to the people who embody its worst impulses. Those impulses have nothing to do with video games. They are versions of impulses that are repeated over and over throughout society.

It is disturbing to comprehend that this defensive and poisonous mob mentality is an intrinsic part of American culture. Yet it is. The monster surrounds us.