This feature is a part of a series on the best films of the 2010s, resulting from our ranked top 25, which you can read here. This is #10.

It is odd to be asked to write about “The Master” in 2019. Primarily because the movie features one of the actor Joaquin Phoenix’s most searing, uninhibited, and revelatory performances. A performance from which he borrows, or at least echoes, or recalls maybe, extensively in this year’s “Joker.”

In “The Master,” Freddie Quell is first seen in the Navy, near and at the end of World War II; his actions and his small but vivid patches of dialogue (as when he describes the best way of getting rid of crab lice) suggest an infantilized sexuality and a near-constant state/pursuit of inebriation. Arthur Fleck of “Joker” has no enthusiasm for drink—he’s already on a bunch of ineffectual meds in any case—and his infantilization extends not so much to the realm of sexuality as to idealized romance.

But both are marginalized people—guys who, in a less enlightened age, many of us might call “losers.” Phoenix gives both men a peculiar, often contorted, physicality. Freddie often hunches his back while putting one or both hands on hips. He’s kind of crablike, especially when he stands on a beach and as masturbates, or feigns masturbation, into the incoming ocean tide. Fleck is more extended, like he’s trying to stretch himself out of his body.

But both characters display their spinal curvatures in disturbing ways. Both show little compunction about putting unfamiliar substances into their mouths. Freddie takes a swig of Lysol, Arthur licks white face makeup off a brush. Freddie freaks out an army psychologist with his answers to a Rorschach test, Arthur alienates his social worker with his complaints that she doesn’t really listen to him.

I’m comfortable admitting these characters are not-so-secret sharers despite the fact that I feel entirely differently about “The Master” than I do about “Joker.” And this essay is not the vehicle in which to contemplate/complain that one of these performances occurs in a box-office-record-breaker while the other, the portrayal of Freddie Quell here, is in a film that made a mere $16 million in the U.S. But that is an interesting factoid, in any event.

Kent Jones’ essay on “The Master” in the September/October 2012 issue of Film Comment remains, to my mind, definitive. In it, he writes of Anderson and Phoenix’s creation: “Phoenix’s Freddie seems like genuinely damaged goods. He and his director feel their way into this man-in-a-bind from the inside out, and they establish his estrangement from others in those opening scenes through awkward smiles and out-of-sync body language alone. A lot is made of Phoenix’s wiry physique and misshapen upper lip, which seems to direct the tilt of his head up and away from whoever he happens to be talking to through a clenched mouth as he feigns an air of skepticism which covers an urge to run. He handles objects with the fragile tentativeness of a child, and his gait is so furiously deliberate and imbalanced that he seems to be avoiding spastic convulsions. This is a performance with a difference, the behavioral creation of an actor and a director with a fierce devotion to the ragged, the unkempt, the authorless.”

Unlike Arthur Fleck, though, ragged and unkempt Freddie finds a savior, or at least a shepherd.

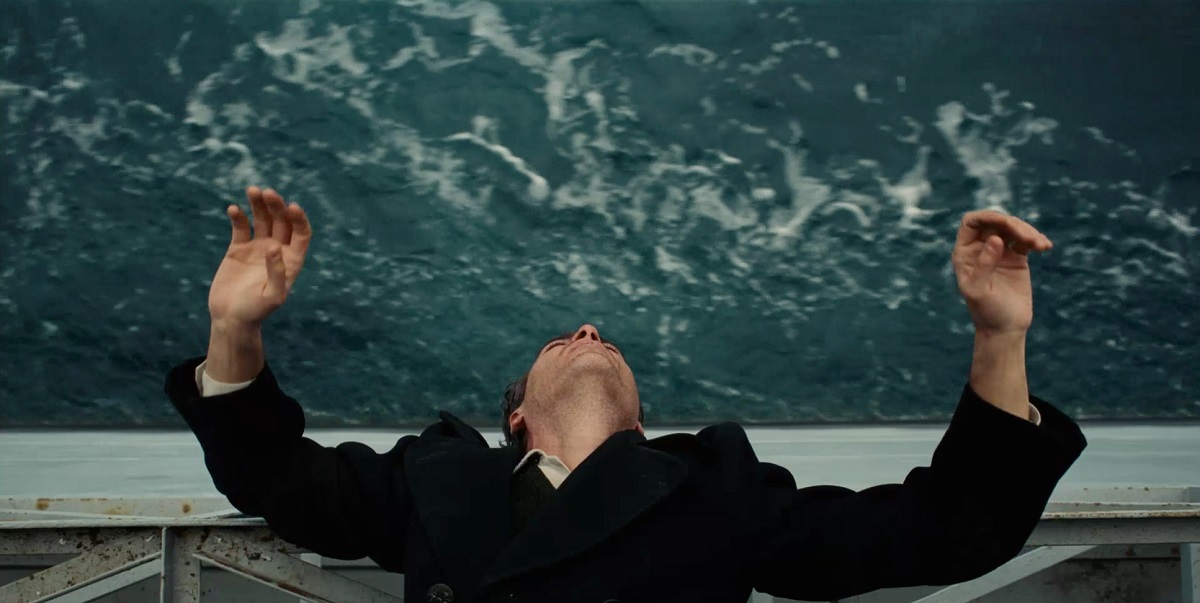

We are with Freddie alone, and very uncomfortably, for the first 20 minutes of the movie: his drunkenness, his drooling sexual humor, his “nervous condition,” his rages, his lying, his desperation, his “nervous condition.” We are with him as he runs across a field chased by those who would possibly kill him, and have maybe not good but definitely coherent reason to, and then we are behind him as he advances toward a pier. Festive music and an array of out-of-focus lights ahead greet him; a steamboat on which there’s a party comes into focus and goes out again. The Alethia is the party boat. Freddie’s salvation and curse are aboard it. We see him from afar, from Freddie’s perspective, doing a silly dance to the silly faux Latin music, in a black jacket and white shirt, fingers pointing upward as he bops. He is Lancaster Dodd.

Freddie wakes up on that boat. His “rescue” has a near-fairy tale quality to it. “You’re safe. You’re at sea,” a woman tells him as her rouses from his slumber. He is then ushered to the quarters of the title character, Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s Dodd, who upbraids Freddie for abusing alcohol and then asks him to recreate the concoction he made for Dodd the blacked-out night before.

“I do many many things,” Dodd tells Freddie. The character is based on L. Ron Hubbard, the founder of Scientology. Perhaps “inspired by” is the more apt term, despite the fact that writer/director Anderson seeds the scenario with a substantial amount of esoteric Hubbard lore. Hoffman, in one of his final screen performances, plays Dodd with a contained strength that masks, sometimes barely, a hopeless and virulent insecurity, one that is fiercely guarded against by Amy Adams’ Peggy, Dodd’s wife. Even as he lies, cheats, commits fraud, damages property, he hangs on to the notion that he is doing good, that he is innovating, that he is contributing to human progress.

One could say that, after Dodd takes on Freddie as a “guinea pig and protegé,” Freddie becomes an enforcing id on Dodd’s behalf. And yet Dodd needs no such thing, as we see when he ends an argument with a skeptic by sputtering “Pig. Fuck.” The relationship of the two characters is more complex in its intertwined nuances and conundrums. “Man is not an animal” is one of the Dodd adages that Freddie hears repeated on first coming into the fold. “Do you often think of how inconsequential you are?” asks Dodd of Freddie during their first round of “processing.” (Freddie answers “yes.”) When Freddie spontaneously destroys the toilet in the jail cell next to Dodd after they’ve both been arrested (and as he does this he wrestles free of his shirt as if it’s a straitjacket, and pops out his right shoulder blade as if trying to dislocate it), Dodd, calmly but almost truculently, notes, “Your fear of capture and imprisonment is an implant from millions of years ago. This battle has been with you from before you know.” And he believes it. And he’s not wrong. This is mere minutes after Dodd’s son waves off Freddie’s concern that he hasn’t been properly following his father’s teaching: “He’s just making it up as he goes along.”

The scene of the two men, side by side, one on a feral rampage, the other trying to illuminate him with an outlandish line of quasi-philosophical sci-fi nonsense that he himself may actually believe, culminating with schoolyard-like taunts—“Who likes you except for me?”—is terrifying and awe-inspiring not just for its blatant content, but for all it implies about human desire and human loneliness and the elaborate, peculiar, destructive mechanisms we construct to cope with them.

This is a movie of unusual density: in all of its two hour and 17 minute length, there’s not a word uttered or gesture made that lacks for numinosity, for presence. Its details become more illuminating and more mysterious, simultaneously, on every repeat viewing. (The movie now also offers the pleasures of seeing early glimpses of now-more prominent talents, including Jesse Plemons, Rami Malek, and Jillian Bell.) And it is not just the particulars of the dialogue and the action. The mural and the chandelier behind Freddie and hometown sweetheart Doris, for instance, and its evocations of courtly love, stuck out on my most recent engagement with the picture.

There’s a sense in which “The Master” paints itself into a corner because there can be no satisfying or just resolution to the Freddie/Dodd intertwining. Perhaps that is the reason why, in the movie’s final quarter, it shifts from dream to reality and back again who knows how many times—but the point, finally, is that in the movie’s circumscribed world there’s no effective difference.

When Dodd sings “Slow Boat To China” to Freddie near the movie’s end, it is emblematic of both the strangeness and the acuity of Anderson’s concept. “If we meet again in the next life, you will be my sworn enemy, and I will show you no mercy,” he says before he begins the not-quite-standard, a 1948-penned Frank Loesser song that’s both inconsequential and evocative. “All to myself, alone,” Dodd sings, in tune, with a slight lilt in his voice and a grave look on his face. There’s no “explanation” for what is going on here nor, I think, any proper or correct interpretation—it’s a scene that calls, critically, for what Susan Sontag called “an erotics of art.”

Which is not to say that there is no “meaning” to the scene. In these two characters, one “inconsequential,” one “not,” flow currents of cultural history feed directly into the present moment, in ways that grow more terrifying by the day.