RogerEbert.com editor Matt Zoller Seitz and film critic Simon Abrams have just released a new book, Guillermo del Toro’s ‘The Devil’s Backbone.’ Below is an excerpt from the new release, which can be purchased here.

38

M: I want to talk to you about the opening of the movie. I actually wrote down the sequence of shots here. First there’s a shot of the entrance of the basement—

G: The door.

M: The door, right. Then comes the falling bomb, then Santi on the floor, and Jaime covering his mouth, and Santi sinking behind him by the water. Then the title image of the fetus with the devil’s backbone floating in amber. You have a lot of metaphors at play here, and that bomb is the biggest one of all.

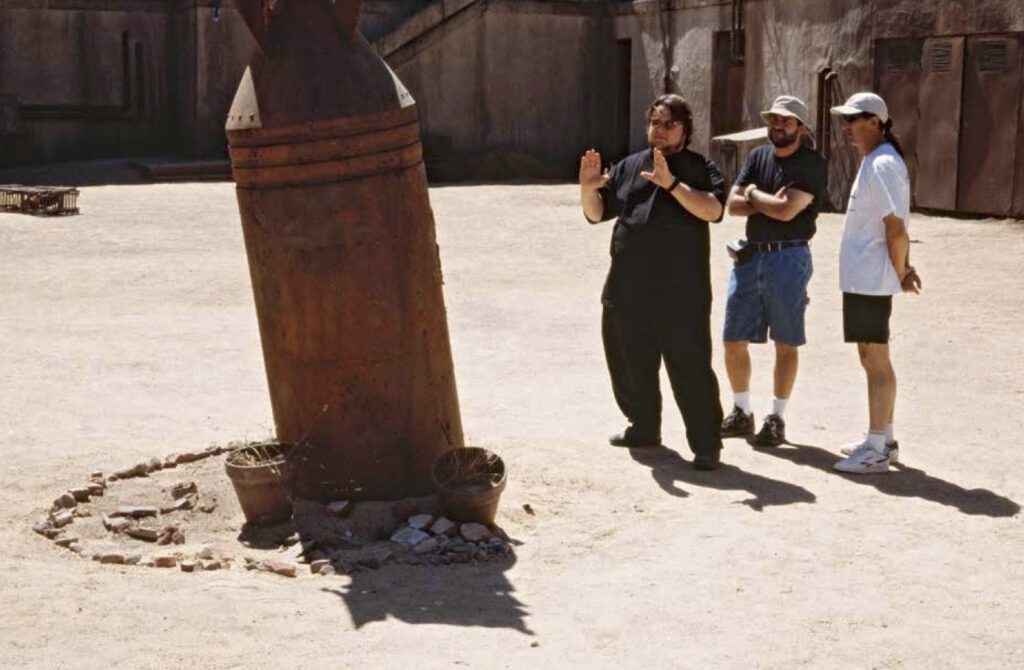

G: That’s exactly what it is. The bomb is omnipresent in the middle of the courtyard much like the war, you know? Like, it just says, “The war is here,” you know? And it’s watching over you. I wanted it to be almost a mother figure to the kids. They plant flowers around it and put ribbons on it, like it’s a fertility goddess, a totemic figure. But I wanted it to look over them the whole time. If you have a bomb in your backyard, unexploded—which I’ve never had, but [laughs]—basically it becomes the north of your entire geography. You know? Whether you sleep close to or far from the bomb, or you cross the bomb to go to the well, it’s always there at the center. But even if you live with a bomb, it’s still a bomb. That’s the essence of a civil war. You live with a conflict and it can become matter-of-fact, everyday, but you’re still living with this bomb at home.

M: I like to think of that bomb as Chekhov’s bomb, except it doesn’t go off.

G: Never! [Laughs.] It’s not funny in a comedy way, but it is ironic that everything explodes except the bomb.

M: That’s true! [Laughs.] There is an explosion, but it’s not the bomb. There is no victory. Some people get out alive; that’s the only victory.

M: Yes—and, connecting the political to the personal for a second, the bomb is a resonant image for all the major characters. When we meet them, there is latent potential—sometimes destructive, sometimes not—that hasn’t been tapped yet, and it’s going to be tapped as the story goes on.

G: You see Carlos put his ear to the bomb.

M: Yes. And the first time we see Carlos is right after he has been orphaned. He’s just lost his parents. This is a kid who’s in shock. This is a kid who’s depressed and withdrawn. In essence, Santi is him.

G: He is.

M: This is a story about Carlos coming back from the dead, which is the story of grief and trauma for anybody who goes through it.

G: If you watch [The Devil’s Backbone] again, you’ll see that I try to give you misleading clues in the beginning. I think that every movie gets better the second time around if you love it. And sometimes you don’t understand why, but it has a pull on you and you want to see it again. Some of the movies I like most, I liked on the second and third viewing, and disliked on the first viewing, but something kept bringing me back to them.

M: Can you give an example of one of the clues?

G: The movie opens like it closes, except at the end of the movie I add one more line: “A ghost, that’s who I am.” That’s the doctor recognizing that he’s narrating the movie—that there are two ghosts in the movie, one doing the narration, and Santi. But that line shows that Casares has made peace with his reality: This is who I am. Spain is a very haunted country, and it’s mostly haunted by the Civil War. So I open with images that, even if you don’t know the story, you think you just saw a kid murder another kid. You see Jaime killing Santi, because Santi’s on the floor bleeding. You see an act of war—the bomb falling. You don’t know you’re going to see that bomb again in the middle of the courtyard. You see the kid with the blood coming out of his head, which was important for me to set up because it’s a visual characteristic of the ghost [that’s] very strong once you see it. Then we come back to all these little snippets in a different way at the end of the film. At the end, you understand how the ghost—the kid that you see get killed—was killed. And you see the floating memories of Jacinto in the water, his photographs that he had in his pocket. And you see the professor trapped within the frame of the building, and the kids going into the distance. Santi has caught Jacinto, but he’s still standing in the middle of the pool. Santi was not liberated.

44

M: “The ghost is frightening but not evil.” That’s a big thing for you. One of the movies you produced for another director, Mama, is a thematic variation on that idea as well. I really like it.

G: Me too. And you know, in terms of investment to return, it’s the most successful movie I’ve ever been involved in. It was done for nothing, and we made over $130 million!

M: The Babadook was a good movie, but I think Mama is a better movie on the same subject. I prefer it in part because of the ending. That’s what really puts it over the top for me.

G: I think so, too.

M: The Babadook is therapy that actually solves the problem, to some degree, whereas in Mama—

G: There’s a loss.

We strategized up the wazoo about that ending. Actually, we talked about it, and we ended up deciding it’s much more anarchic and iconoclastic if the happy ending for one character is inconceivably wrong for the other. The little girl in Mama was raised by the ghost. The other girl was five years old when she lost her mother. The older girl had a sense of right and wrong. But because the little girl was raised by the ghost, she wants to go with the ghost. To live with the normal couple would be incredibly boring for her.

The result is one of those endings that is rare in commercial cinema. I said, “Look, if we make the audience cry, the ending will stay. But if they are outraged about the kid going with the ghost, we’re gonna be in such trouble.” We were bracing ourselves when we tested the movie because it was the only testing we had. The entire audience was weeping at the end.

M: One of the many reasons I love horror so much is that it’s the only commercial genre left where people go in knowing there’s a chance of an unhappy ending, and they accept it. I mean, so far they do. It might eventually get to the point where science fiction is now. I think audiences have lost that openness to unhappy endings in science fiction, for the most part. Once in a while you get a sci-fi film with an unhappy ending that makes money, but it’s pretty rare now. The action film has succumbed, and I think thrillers have succumbed. Even the paranoid thriller, which in the sixties and seventies was defined by ambiguous or unhappy endings, has succumbed.

G: Most of them. You don’t get a Parallax View or Three Days of the Condor nowadays.

M: Truly paranoid movies have to leave you feeling uneasy. They can’t end with the corrupt official falling off a ledge and getting impaled on the American flag and everybody goes home. In 1998, Gene Hackman played essentially the same character in Enemy of the State that he played in The Conversation a quarter century earlier. The Conversation has a downbeat, ambiguous ending where the faceless, sinister institution is still in control. In the other movie, Gene Hackman exposes the bad apples and the good guys win. That’s not a paranoid thriller; that’s escapism.

G: There’s always a senator who is honest and a senator who is dishonest; a cop who is nice and a cop who is bad. It’s not so honest, it’s not so black-and-white, in real life. And you know, textually, some of these movies are very real. You watch them and think, That’s very gritty and real. But anecdotally, no. They’re very, very simplistic. That’s why almost every single movie about drug dealing in American cinema is completely hypocritical, because the attitude is, Yeah, if we can just get the bad guy . . . There is no bad guy. The fucking system is what is the bad guy. Drugs are used to pay for black-book operations in America. The participants in the Iran-Contra scandal were using cocaine to pay for a dirty war! All the billions of dollars that go into the black books of the CIA to finance infiltrations, you know—it’s not happening because of “bad guys.” It’s systemic! And no one in movies addresses this. Look, the genre I love and the genre that influences me, even if I don’t do straight horror, is the fantastic. It is what I want to do, and it is not a prestigious genre. Somebody broke down all horror movies into three structures: the horror within, the horror from outside, and the horror that either gets within from outsid —or goes out into the world from within. That’s every horror movie ever made. In Alien, the threat is from the outside in.

M: And yet, the Xenomorph also reflects the sickness in that society. This corporation wants to use the alien as a weapon.

G: Yes, and the monsters are more valuable to the company than the humans.

M: The alien stands in for the capitalist system that runs everything in the galaxy.

G: And wants to devour it all.

M: It’s a remorseless, devouring creature that just wants to replicate more of its own kind. Alien’s a political film!

G: It is! Every film is a political film—

M: The good ones are!

G: And the bad ones, momentarily, too!