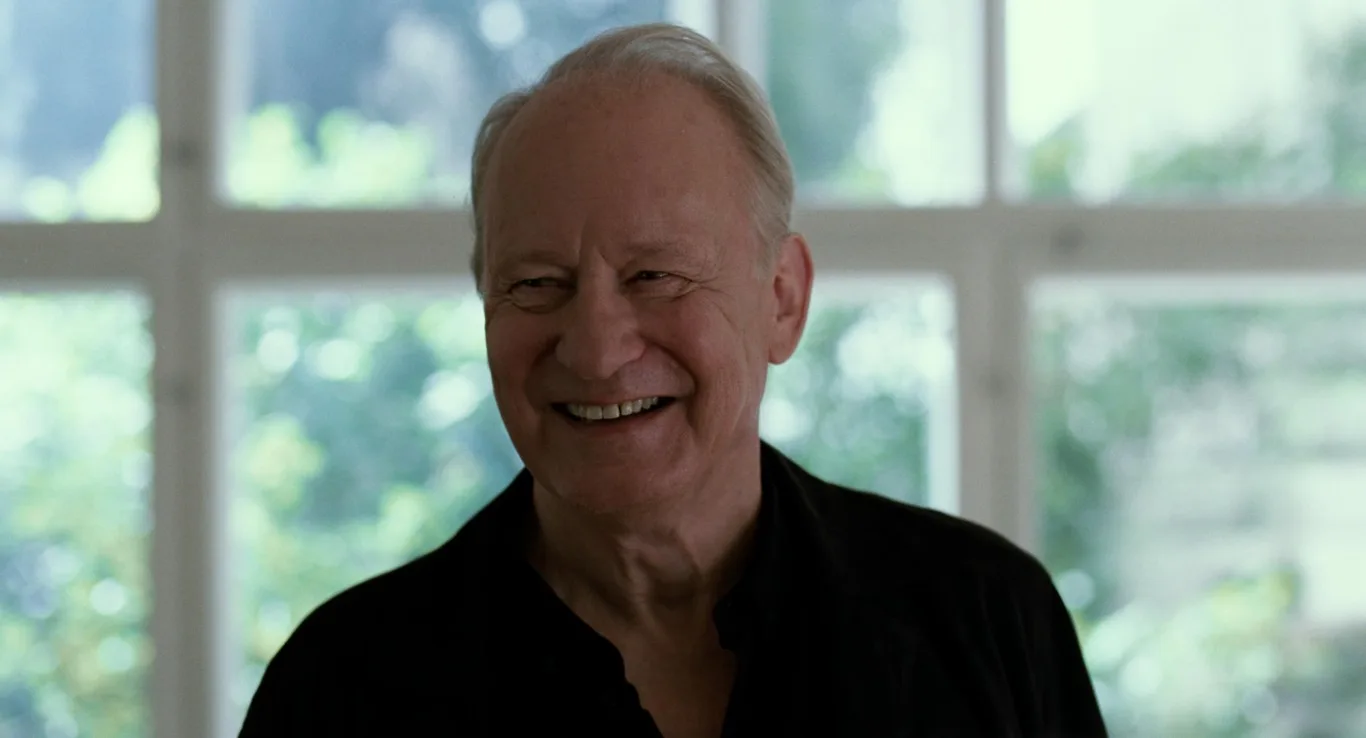

A profoundly moving portrait of a family reckoning with the painful memories embedded deep within the walls of their ancestral home, Joachim Trier’s “Sentimental Value” finds the filmmaker reflecting once more on the existential themes—of time, love, identity, and history—that have abounded throughout his career.

The film reunites Trier with Renate Reinsve, a Norwegian actress whose performance in “The Worst Person in the World” earned her the award for Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival; as a theater actress revisiting old wounds, her performance—opposite that of Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas as her younger sister—distills the kind of agonized emotional clarity that has governed Trier’s recent work.

Stellan Skarsgård stars as Gustav Borg, their father and a once-celebrated filmmaker whose efforts to repair his relationship with his two daughters are complicated by his interest in revisiting his own, fraught familial experience—including the suicide of his mother, who suffered during World War II under Nazi occupation, and whose lingering loss factors into this recent work. For Trier, the film is personal; his maternal grandfather, Erik Løchen, was one of Norway’s better-known filmmakers, as well as a jazz musician. During WWII, he was in the resistance and was captured, spending time in work camps and barely surviving; though that trauma lingered throughout his life, Trier believes his grandfather made films in part to process his pain. His presence is indirectly felt in “Sentimental Value” through the voiceover narration of Bente Børsum, who appeared in Løchen’s “The Hunt.”

Ahead of “Sentimental Value” opening in theaters, Trier sat down for a wide-ranging discussion of his film’s poignant themes, the challenges and joys of working with time, his unique personal connection to this story, the inescapable influence of Ingmar Bergman, and much more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

I’ve always felt that you identify so strongly with your characters—that the empathy of your filmmaking flows from your impulse to understand and connect with them. You come from a film family, and I’m curious about drawing on that personal experience in shaping the characters of Gustav Borg, his daughters, and Rachel Kemp.

It’s true. I think the idea of identification comes first from a writer’s point of view, then from a director’s, and finally from a collaboration with the actors. I need to understand them and identify their yearnings and their struggles. But that’s not the same as saying that the characters are biographically like me, or that you don’t need to vary up the characters. Still, this is a polyphonic kind of story, and so it’s nice to have that identification.

For example, Gustav is a film director. As you say, absolutely correctly, I come from a film family background. Without him being anyone I know, I understand the struggles and the joys, the passion for making films, so I identify with that—and also the anxiety, perhaps, that it will come to an end, that “one day they won’t let me,” which is what he’s going through. But this film was also about having characters like the younger sister, played by Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas, who was in Gustav’s film as a child and certainly didn’t want to be in front of the camera again—something completely different.

With her, for example, I found this identifiable point: she wants everyone to connect and feel good. I have that in me. I always want people to get along. You do find something with all of them, after a while, when working on them. But the last thing I’ll say is that I don’t want to hinder the possibility of the actors coming in and taking charge of the characters. It’s good to leave an open space for them to fill in, as well.

The term you use, “polyphonic,” refers specifically to sound. I’m curious about your creative relationship to music, score, and especially sound design, as this was your father’s craft. Your film opens and closes with two wonderful tracks, Terry Callier’s “Dancing Girl” and Labi Siffre’s “Cannock Chase,” but how do you think about the role of sound design in your filmmaking?

Thank you very much for asking that. I really care about it. When I talk to friends about using music in film, I also tell them that one of the joys of life is the system of loudspeakers and the richness of frequency you get in a good cinema. It’s the best sound you’ll hear anywhere in the world. It’s a super hi-fi, complex, surround-sound experience. I feel that sometimes filmmakers forget how subtle you can be while still including a lot of sound and using the full range of frequencies. Hammering, loud sound doesn’t necessarily use the possibilities of a theater.

That’s something I think I’ve learned from my father: that you can create what feels like silence but is actually a full sound design of atmospheric subtlety. I love loud pieces of music; I love noise, but I also love the dynamics of daring to be quiet and gentle with sound. It’s almost like you draw the audience into the image by being very cautious about sound in certain areas.

For example, towards the end, there’s an almost climactic scene between the two sisters, full of emotion and action. And there’s no music. I tried to really build towards that feeling of presence: being there, hearing the breathing, all the movements of clothes. That can ultimately be so strong. Sometimes, when it comes to people talking about sound, they always talk about the loud films—And I think that the opposite could be equally complex and interesting.

Everyone has a childhood home, a place where they grew up; this film explores the poetics of such a location. You’ve referred to the house as a “witness of the unspoken.” But there’s an emotional residue in the house’s atmosphere; it reflects all this lived experience. What can you say about first conceiving of the house and its presence, and of mapping your story onto this setting once you had a physical location?

First of all, our spatial treatment of the narrative—to refine it so that it fit the space—was an exciting, visual task. When we write, Eskil Vogt and I write for the image in a way, and for the actors, but I think the sound aspect is really interesting as well.

Hania Rani was our wonderful composer; this was the first collaboration I’ve had with her. She wanted to go to the house and record its reverb and other sonic qualities, which, to me, was fascinating. I’ve never had anyone think like that, but she said it inspired and affected her approach to reverbs for certain pieces of music as well. The idea of sound always being present is very interesting to me.

And to elaborate on that spatial treatment of the narrative, this film required characters to move between rooms and down corridors, and it needed a location with a room that could be dressed to play different roles over time. We first see Nora enter the house through what had been her mother’s psychology office, where there’s still an empty chair… How much did the story change once you had a location, and how much did the narrative dictate the location you were looking for?

It was a bit of both. The first draft contained pretty much the story you see in the film, but the relationship between the upstairs and downstairs—and that hallway corridor towards the room where such dramatic events we realize throughout the story had occurred, all of that repetition of angles that is so fun to play with in movies—I think this house really gave itself to that. Along with our wonderful production designer, Jørgen Stangebye Larsen, we also built a replica of the house. In addition to shooting in the real house, we had a studio version so we could go between them.

The studio version got dressed for every 10 years of the 20th century, with different wallpapers and different moods. A lot of that was done through research; we also had in the studio these VP walls—virtual production walls—where we created an exterior, based on research, photo-realistically showing how foliage grew over time and how buildings were erected suddenly as others disappeared. We drew a map of time through the house and its surroundings.

You actually built a replica of the Borg family house on a soundstage to film a montage of the house across generations. What effect did that have for you, given the relevance of that filmmaking technique to the story? Gustav is so fixated on filming this deeply personal story in the actual house where so much has happened.

I’m primarily a location director, so I always feel it’s wonderful to look out the window and receive a gift, as something will happen that makes it feel close to life. But, actually, with the team we had, the studio experience was wonderful, as was the feeling of being able to create specific moods with a lot of control. So, control and chaos were both alive in this process, in new and unusual ways for me.

The replica house made me think about how directly you depict time in this film. How has your temperament toward dealing with time, which you’ve described as one of the primary aesthetic considerations a filmmaker can have, evolved with this film?

It’s such a great question, and it’s an essential one to the core of this story. The aspect of time begins with the film’s opening, which shows Nora, the eldest daughter, and her essay on the house’s perception of her family history. It’s the idea that, for the house, a human life is very short, because the house is a constant, in a way; it’s this longer, lasting structure. I thought that was a nice setup for a story about reconciliation, where the adult realization of the sisters that they’re not going to have their father around forever—even though he’s a complicated character—means they, in their own individual ways, have to reconcile their relationship with him.

That’s one aspect, but it’s also a possibility to put the idea of social history into context when we realize through the film that the Second World War and the Nazi occupation of Norway were affecting the lives of families, and many people’s lives, in ways that still impact us. Many people say that a war trauma takes three generations before it lets go. For people who haven’t seen the film yet, that’s not in the forefront of the story, but it’s there in the house, and the idea of the house witnessing life helps us tell that story.

It’s Agnes who seeks out more knowledge about her grandmother’s experiences during the war, and this has a profound effect on her. It’s my understanding you’ve personally been through that process of tracing your family history back into that conflict.

My grandfather was in the resistance during the war; he was captured and spent time imprisoned by the Nazis across two different camps, and he was very traumatized by that. He made films after the war, and I think that was a way to survive and find a place in the world again. He was creating something and seeking meaning in it.

I think that’s at the core of the process of making this film for me, but also the idea of the National Archive, the accounting of facts in a society, is fundamental. It’s a different narrative from the fictional one of the National Theater, where the older sister works; it’s the historical aspect of how necessary it is for democracy and society to hold themselves accountable to facts.

I found, through a piece of paper, a witness to the accounts of my grandfather’s imprisonment. It’s provable. No one can deny there’s proof that a terrible thing happened to him. With where the world is right now, that’s a very important thing to remember: that we need to learn from history. And I think the film asks this question of the ambivalence of history and memory. On one level, we need to forget, to forgive a difficult parent.

On the other hand, we owe it to the past to remember certain things, not to repeat those faults. And we owe it to the people who experienced certain things. That’s the space where we live in time, in between those two notions.

It’s better to live in impermanence than in any kind of finality, in how we reconcile with the past.

Life is a process—and making films is a process. Now that I have talked a bit about this film, and you’re asking me about memory and time and our relation to it—and also the process of making a film—there’s always that retrospective narrative that now is slowly being created as I’m talking to journalists.

But it’s a narrative that will never quite mirror the process, because in making it, you’re lost along the way. You think it’s about something, then you discover something else. It’s ongoing, but it’s nice, at the end, to try to summarize: “What the hell did we make?” and to meet people who can mirror it back to us.

To bring Gustav into that theme of excavating memory… Nora works within the theater, and Agnes explores the archives. As we see in Deauville, during a retrospective of his work, Gustav has been speaking through his art, making films like the one whose ending we see: a wartime drama about an orphan’s ordeal. What is he reckoning with?

“Anna,” yes. We thought a lot about that, actually, since we knew that Gustav is a character who’s quite clumsy at relating to people socially, particularly his family and his daughters, but whom we realize has a more sophisticated, emotionally engaging way to create art. It was very important that those films expressed some aspect of him; in the piece of his film we see, though more pieces didn’t make it into the final cut, the ending of “Anna” obviously deals with some sense of survivor’s guilt.

We later realize perhaps why that is a major theme with him. It was important for us to use everything in this film to get into character and to explain the layers of observation about human beings’ incapacity for communication, while still revealing them. That was an interesting way into him, the films.

Gustav speaks through his art in a way that he cannot in life; with the film he wants to make, it’s about his mother and his daughter, but it’s also about him. He’s trying to express something deeply personal by speaking through them. But one wonders whether he wrote this script specifically to bring about personal reconciliation, or whether he wrote it to revitalize his career because he knew it would be creatively stimulating.

My feeling is that you have a really great understanding of the complexity of that in your question, and I’m almost hesitant to answer, because I think you’ve put it very beautifully. There are a lot of different things going on with him, I think you’re right. It’s interesting for the audience to consider whether Gustav’s primary urge is reconciliation. Does he want to do something with his daughter? Or is it primarily just wanting to make a film? Or is it mainly to resolve his relationship with his mother and the trauma around her death? Or is it everything, and he’s confused, and he doesn’t know, and he doesn’t quite have to know, because at the end of the day, he knows how to craft a movie, and that’s what he does? All of those things could be playing out at different levels of his psyche at the same time or at different times.

Tell me about your relationship with both Eskil Vogt, your co-writer, and Olivier Bugge Coutté, your editor. You’re long-time collaborators. How do you work together?

Those two are people I’ve worked with since my short films and have made all six features with. I think Eskil is a starting point, then he leaves the project for a while, and I go and direct it—he’s not very involved at that point—and then, halfway through the edit, Olivier and I feel we have reached a place where we need feedback, so we show it to Eskil, and he comes back in. We sometimes have terrible arguments, but we always end up friends, all of us.

Olivier is all about what is actually at play in the material, and what the best version is now, while Eskil sometimes reminds us of the thematic complexities we shouldn’t lose. I’m the director in the middle, trying to listen as skillfully as I can to these smart people, to try to get it to land in the right place. It’s one of the most exciting things to have collaborators you’ve worked with for a long time. You have shorthand, so you can go deep quickly and get into the core of the challenges every new film will automatically present. It’s tricky making films and getting the balance right. That’s the art of it.

To the point, I felt your use of close-ups on your actors’ faces was beautifully balanced in this film. I know that’s been a fascination of yours through your career—and I love this film’s reference to “The Piano Teacher,” a film featuring one of the most unforgettable close-up shots: at the end, her with the knife. What’s the secret to maintaining that kind of proximity with actors, and what’s your process of knowing when you’ve found what you’re looking for in an actor’s expression?

I sit next to the camera and have a handheld monitor to check the frame, but I look at them with my eyes and try to feel what’s going on. That’s the best way of judging it. There is a very inspiring clip of Ingmar Bergman on set for one of his last films, in which an actor questions whether they got it right. And Bergman says something along the lines of, “Well, I felt it, and I don’t squander emotions with you guys. Let’s move on. I’m sure we could do a million other great versions, but I felt it now, so I’m done with this. Let’s move on.”

At the end of the day, we try a lot of variations, but if I feel that we’ve explored it properly, it’s not a rational thing. You’ve got to trust your gut and say to the actor, “I’m really pleased with this. Thank you. You gave me a lot of your experience of the scene. Let’s move on.” And that’s the art again: when do you call it? There’s a programmatic side to it, of course, having limited time and all that. But I felt that, in this one, we got to explore the material at hand deeply. I’m very grateful and happy for that.

I’m glad you brought up Bergman. One film I sense reflecting into this one, and not just because of the family Borg, is “Wild Strawberries.” I’m curious about how film influences you. But to frame that question more expansively, “Sentimental Value” is narrated by the Norwegian actress Bente Børsum, now 93, who worked with your grandfather on “The Hunt.” How did you think, with this film, about working with both your own family’s history and this larger lineage of Scandinavian cinema?

There are a lot of interesting things to talk about there. I’ll start with Bente, and then go to Bergman. Yes, Bente played the lead in my grandfather’s 1960 film, “The Hunt”; both were very young. It was her first lead role. It was his first film.

Long story short, I actually have a gym close to my house where there are a lot of old people present—a physiotherapy center, really—where it’s cheap to go and work out. And I went there and suddenly felt very young amongst all the old people; suddenly, I realized that Bente Børsum was there. I’d just met her briefly, but we got to know each other. We met there on Sundays, sometimes during our workouts/ I thought, “What a magnificent chance to work with her.” I never really had a part I could offer, but I could do the narration, and it suddenly clicked that she knew my grandfather.

She also has this beautiful narration about Agnes going to the National Archive, which you and I spoke about earlier, and she could talk about those things with great authority, as her mother was captured during the war. I know that’s a very dear theme to her: the grief and woundedness of the war, even though it was so long ago, she still carries that. That was a really wonderful thing, to have a little homage back to my grandfather’s first film.

When it comes to Bergman, I am very happy you brought up “Wild Strawberries.” That’s such a gentle yet deeply melancholic film about an old man asking questions of whether he lived the life he was supposed to. Did he connect, or why didn’t he connect with certain people? I think that’s very relevant to Gustav’s story.

It’s hard to talk about Bergman because he’s at play in so many indirect and unconscious ways for me, I’m sure. It’s always a problem when I say at home that Bergman inspires me; everyone wants to take me down a notch. “Oh, you’re not Bergman. He was much greater.” I’ve had a couple of asshole critics who are, like, “Oh, he thinks he’s Bergman.” I never thought I was anything. Ozu from Japan inspires me, as do many American filmmakers, as well as Bergman.

It’s just the ongoing process of being a film lover and seeing what film is capable of, trying to take that energy and bring it somewhere else. I think that’s unavoidable—because I’m Scandinavian, everyone thinks it’s Bergman, and that’s not a lie, but it’s so many other things as well, is my point. [laughs]

“Sentimental Value” is now playing in select theaters, via Neon.