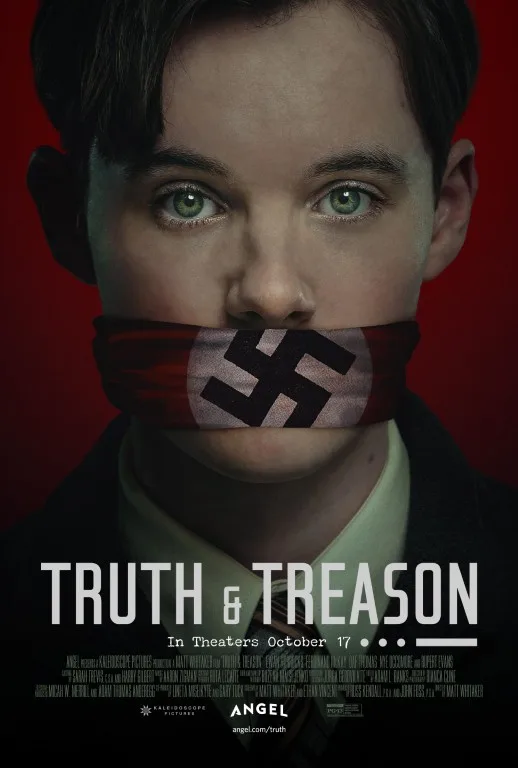

“Truth & Treason” is painfully straightforward. Matt Whitaker’s World War II period piece about the 16-year-old German resistant writer Helmuth Hübener (Ewan Horrocks) moves, looks and sounds like plenty of other stiff biographical films. In this Angel Studios produced film we’re quite literally plunged into the Spring of 1941 in Hamburg, Germany where four adolescent boys: Helmuth, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe (Ferdinand McKay), Rudi Wobbe (Daf Thomas), and Salomon Schwarz (Nye Occomore)—are riding their bicycles through the countryside. When they arrive at a river, they take turns jumping from the bridge down into the tranquil waters. Though a frightened Helmuth is the last to leap, the scene serves as the metaphorical moment he and his friends decided to face a challenge, foreshadowing their eventual defiance of Nazi Germany.

That entry point is a fairly on-the-nose piece of symbolism that isn’t necessarily cheap, but it isn’t exactly memorable either. The film’s structure is literal and chronological, guiding us through the final year in Helmuth’s life, from that daring jump into the river to his eventual conviction for treason in the Fall of 1942. Considering Whitaker previously wrote and directed “Truth & Conviction,” a 2002 documentary about Helmuth, you would expect that familiarity would grant him the safety to take a spontaneous approach. But outside of the curious decision to rely on a British cast, that mostly isn’t the case here. Instead, “Truth & Treason” is a staid drama whose observations about Helmuth could easily be summed up in a quick encyclopedic blurb.

By all outward appearances, Helmuth seemed to be the ideal product of Nazi Germany. He served in the Hitler Youth and attained an internship at City Hall (he was the youngest intern ever to be hired at the time). His parents were both devoted National Socialists; his father devoured the local propagandist newspaper. His older brother also served in the German army. Helmuth’s faith is shaken, however, when said brother returns home with a shortwave radio that’s capable of tuning into the BBC (the very act of listening to banned foreign music was considered treason). On those channels he hears a different perspective about the war. Solomon, his Mormon-Jewish friend, also begins to be targeted, specifically by the antisemitic bishop of his Latter-day Saints church. When you combine those factors with the fact that working at City hall gave a smart kid like Helmuth access to banned books, then well, you’ve now got a revolutionary.

By borrowing a typewriter from church, Helmuth begins to type out anti-Nazi pamphlets on red paper, which he then stuffs in people’s mailboxes on neighboring windshields. Before long, he even enlists his friends Karl-Henze and Rudi to help. Their seditious acts quickly come to the attention of Gestapo investigator Erwin Mussener (Rupert Evans), who becomes obsessed with discovering their identities. That pursuit doesn’t engender many surprises. Sometimes we switch perspectives, which includes Erwin’s vantage point, which gives us a sense of the investigation and why he might be crueler than your standard-issue Nazi. The film also grants Helmuth a love interest in a fellow worker at City Hall while it dispenses Helmuth’s literary influences.

Despite that work, Helmuth remains a symbol for defiance rather than psychologically complex person, with his religious consternation in particular falling by the wayside. Instead, the film fashions Helmuth as a kind of Joan of Arc figure. That saintly perception aesthetically occurs via an overuse of backlighting, a favorite approach of far too many cinematographers attempting to frame their protagonists with a kind of visual heroism. When the film shifts to Helmuth’s imprisonment, Whitaker then opts for extreme closeups whose intent is to embed us in Helmut’s resoluteness in the face of his traumatic torture—an objective given great weight by Horrocks’ physically intense performance. While these technical methods certainly engender empathy, they’re so one-note their bluntness offers little room for an enlightening thought.

To be clear, “Truth & Treason” is exactly the movie it wants to be. In fact, through Angel Studio’s pay-it-forward system, which will grant you access to a longer four-part limited series—which will probably explain this film’s cliff notes shallowness—you might discover that the series is exactly what it wants to be too. It’s just that what it wants to be isn’t all that interesting. And while there’s value in learning a lesser-known story, particularly one about defying fascism, especially at this present moment, shouldn’t the rarity of telling this story provide an even greater desire to reach beyond one’s stylistic safety net? Shouldn’t the approach be as defiant as the subject?