The day is May 24, 2011, a grey, drizzly, and mostly unremarkable Tuesday. I am sitting in a room with a number of other people, all of whom would no doubt prefer to be somewhere else at that particular moment. Finally, a man steps up into the front of the room, briefly introduces himself to us and then begins earnestly discussing the career of William Wyler with a focus on the latter portion—the success of “Ben-Hur” (1959) and how he turned down the chance to make “The Sound of Music” (1965), though not a mention, as I recall, of “The Children’s Hour” (1962). Under normal circumstances—say a college class or an introduction to a screening—this talk might make some sort of sense, but these are not normal circumstances, and I am convinced for a moment that I am finally cracking up. Not only that, I can feel the stares of some of the others in the room who are a.) equally confused by all the movie talk and b.) presumably convinced that I am somehow responsible for it.

You see, when I said, “these are not normal circumstances,” what I meant to say was “this is my father’s funeral,” and when I said, “a man,” what I meant to say was “the pastor conducting the service.”

Dad, Raymond W. Sobczynski, had passed away a few days earlier the age of 76—he had been in poor health for the previous few years and had spent about three weeks in the hospital before finally passing on. As such things go, I suppose that he went as well as one could under the circumstances—my mother, my brother, his wife, and I were all there at his bedside. While it hurt, it was perhaps not a shock, and it at least brought an end to his suffering. As anyone who goes through the death of a loved one can attest, the next couple of days can be an oftentimes surreal whirlwind that finds them caught between trying to emotionally process the loss while at the same time trying to take care of all of the various details that suddenly crop up, especially regarding the funeral and all that.

Since dealing with people is not exactly my forte, one of my key jobs was to jot out a brief obituary that the pastor at the funeral home could use to glean details for the service he was going to deliver for someone I don’t think he had ever actually met. Therefore, this extremely bizarre opening is probably the result of something I wrote but I do not have the faintest idea of what it could have been—I can assure that even under the best of circumstances, I would rather eat glass than contemplate the existence of “The Sound of Music,” let alone make reference to it regarding my dead dad. Finally, at just about the moment when I am about to stand up and ask some variation of “WTF?” (and while the talk thus far may not have gone on for too long in real time, it feels to be as if it has gone on forever), he shifts the talk from the nun musical to the film that he made instead of that one, “The Collector.“

Finally, it all makes sense, sort of. I may have temporarily forgotten that Wyler directed “The Collector,” but there is no way that I can ever forget the film itself. To these eyes, it is probably the most significant movie ever made, because if it didn’t exist, there is a good chance that I wouldn’t exist either. (Granted, after a few more paragraphs of this, some of you may be thinking that might be a bad idea, but let us play nice for the time being.)

In 1965, Raymond met Patricia Kribble while riding the train into Chicago for work. From what I have been led to understand, she did not seem especially interested at first—I gather she was under the mistaken impression that he was already married—but she eventually agreed to go out on a first date with him. The evening planned was typical enough for the time—a movie at one of the city’s big theaters, dinner afterward at the Playboy Club, and perhaps coffee if all went well. Now, around this time, there were any number of films that one could have chosen from—“What’s New, Pussycat?,” “Cat Ballou,” “The Great Race,” “Von Ryan’s Express,” “The Family Jewels”—but Dad, in his wisdom, picked “The Collector.” Now this may not seem like a big deal to those of you who are unfamiliar with the film but let me hasten to assure you that if you were to compile a list of the absolute worst movies to choose to see on a first date—ones that would almost certainly guarantee that there would not be a second—“The Collector” would have to reside pretty near the top.

Based on the 1963 debut novel by John Fowles, the film introduces us to Freddie (Terence Stamp), a socially maladjusted young man with a fascination for capturing and collecting butterflies. After winning a sizable chunk of money in a football pool, he uses it to purchase a remote 17th-century farmhouse in the countryside. He then begins following—we would call it “stalking” today—pretty art student Miranda (Samantha Eggar) around London, and one night, he quietly pursues her outside a pub, chloroforms her in the street, and takes her back to the farmhouse, where she wakes up in the cellar. Miranda at first assumes that she has been kidnapped for ransom and insists that her family is not wealthy, but the truth turns out to be much ickier. It seems that Freddie has been following her for years, ever since they used to ride on the same bus line. He now proclaims his love for her and states that he will keep her for four weeks, which he feels will be enough time for her to really get to know him and reciprocate his feelings. If she doesn’t, he assures her that he will let her go with no problem.

As you can probably surmise, this plan does not go especially well. Freddie offers her certain concessions—things like access to sunlight and supervised baths—in the hopes that they will prove the sincerity of his intentions towards her. Instead, she begins to undermine him psychologically—at one point, she informs him that while she will not offer resistance if he attempts to rape her, such an act would be greatly disappointing to her. She still makes attempts to escape or get word out that she is being held captive, but is stymied at every turn. The end of the four weeks finally arrives, and with it, Freddie’s proposal of marriage—Miranda accepts, but he does not quite buy it, and she then tries yet another escape attempt. This kicks off a chain of events that leads to Miranda’s dying and Freddie, after burying her body out back, deciding that the failure of his plan was all her fault and commencing the stalking of a new and different woman with whom he might have more success.

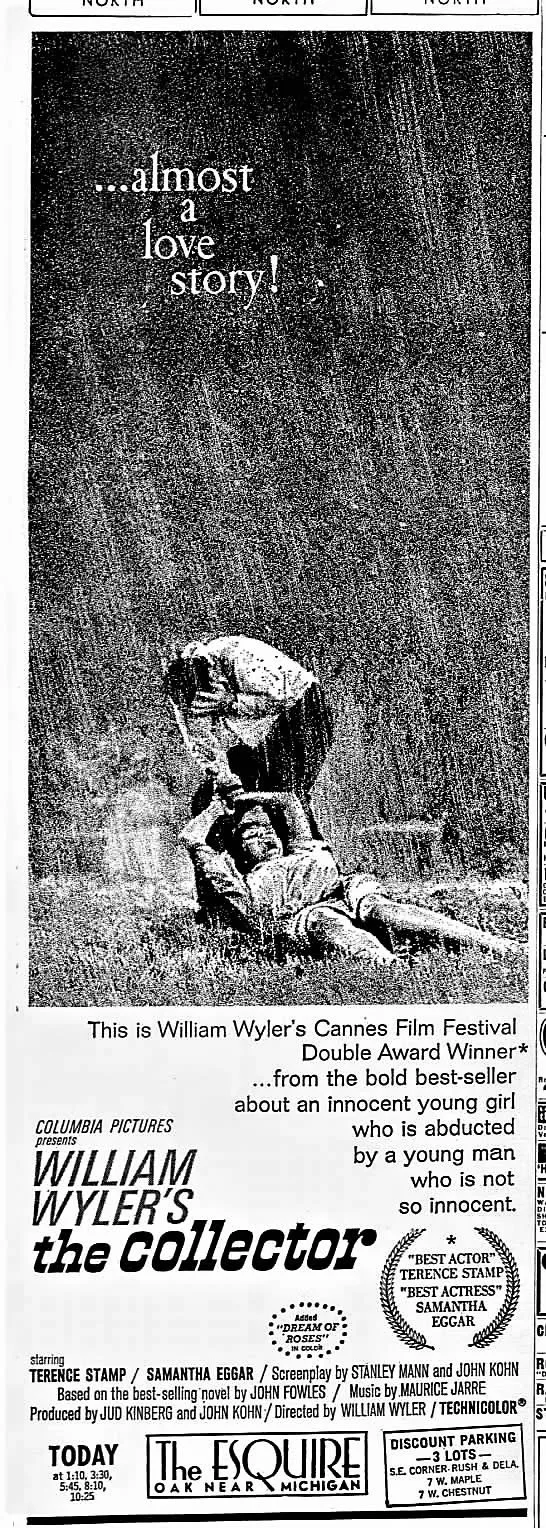

Now make no mistake about it—“The Collector” is an undeniably creepy and compelling psychological thriller featuring excellent performances from the two leads (who both won awards at Cannes a couple of months earlier for their work), a real sense of mounting tension through Wyler’s direction and a finale that stayed true to the bleak nature of the novel instead of gutting it by slapping on a wholly inappropriate happy ending. (Supposedly, an alternate ending, one written by Terry Southern in which Miranda did manage to escape, was prepared but quickly rejected by Wyler.) That said, it is definitely the kind of film that you do not want to spring on someone completely unawares, especially in a first date situation. Somewhere in the archives, I have a scan of the newspaper ad that ran during its run at the Esquire, the gorgeous Art Deco theater where it was playing. It is not exactly restrained—the visual is of Freddie dragging Miranda on the ground, the tag line is “…almost a love story!” and it goes on to read “…from the bold best-seller about an innocent young girl who is abducted by a young man who is not so innocent.” Hell, even the legendary “Keep Telling Yourself—It’s Only A Movie!” ad from “Last House on the Left” (1972) showed more subtlety and nuance by comparison.

What could have possibly led him to believe that this was the right call to make? If he had read the book or if he had seen that ad, I have to believe that he might have rethought the decision. I cannot imagine that the Cannes victories would have made any difference to him. Did a friend recommend it to him, perhaps not entirely explaining what transpired in it? I have to assume that he simply had no idea what the film entailed and just figured it would be one of those straightforward British dramas that were making headway in the U.S. around that time. The only other explanation that makes sense—the one that actually makes the most sense, now that I think of it—is that he was thinking more about the dinner and picked the film simply because the Esquire was just about the closest theater to the Playboy Club.

What made “The Collector” such an insane choice is that if you were to try to pick a film that was guaranteed to alienate and upset my mother, you could hardly do better or worse than that one. Never exactly a big cinema buff under the best of circumstances, she hates most things that smack of the horror and thriller genres and especially dislikes movies that have the temerity to end on a down note. (She was so consistent on this point that she even used it to explain why she didn’t like “Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood,” stating that she knew what had really happened in the end.) If she had even an inkling of what the film consisted of, not only would she have said “not a chance,” but there is an excellent chance that the entire date would have been scuttled. Think I am kidding about this? She once regaled me with the story of how the guy she was seeing a few years earlier had invited her to see “Psycho” (1960), and she absolutely refused based on the title alone. (Insert facepalm emoji here.)

Needless to say, the movie did not go over very well with her and as someone who has seen her react to movies that she doesn’t like with a form of low-key hostility that could freeze the blood (after sitting through the film of the same name, simply invoking any derivation of the phrase “Comin’ at Ya” would invoke a response roughly akin to the typical response to asking the location of the Susquehanna Hat Company on Bagel Street), I can practically see the look of disapproval on her face she must have sported throughout. However, she must have been in a forgiving mood—that or the food at the Playboy Club and the coffee at Cafe Bellini must have been spectacular—because she did agree to see him again after all. Two years later, on the same date that this piece is being published, they got married—an occasion that featured something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue and a bomb threat at the reception (a tale that to be told another time)—eventually got around to having me and, a few years later, my brother and stayed together until the day he passed.

Sadly, not much tangible remains from that fateful date. Venerable Mom passed away a decade after my father, and the Playboy Club and Cafe Bellini are long gone. The Esquire, which inexplicably was denied landmark status, underwent a conversion that reduced its grand 1,400-seat auditorium to a bland six-plex before being closed in 2006. As for “The Collector” itself, its premise would get a comedic spin from Pedro Almodovar a couple of decades later with his controversial hit “Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down,” and I suspect that nearly every one of the violent police procedural shows of the last decade, things like “CSI” and the various permutations of “Law & Order,” has probably lifted chunks of its plotting for an episode or two. While the film may not have a profile as high as something like “Psycho” or other suspense thrillers of its type, it still packs a considerable punch even today. And yet, when the occasion comes when I do happen to watch it, I cannot see the brutality, the bleakness, or the psychological torment at all. All I can see is the romance. Thank God William Wyler picked this instead of The Sound of Music. Same goes for my dad.