Reid Davenport is a brilliant filmmaker who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. He is part of what he calls the Disability New Wave of movement in filmmaking. He makes movies about the experience of being disabled and society’s attitudes towards the disabled, from condescension and pity to discrimination and hostility.

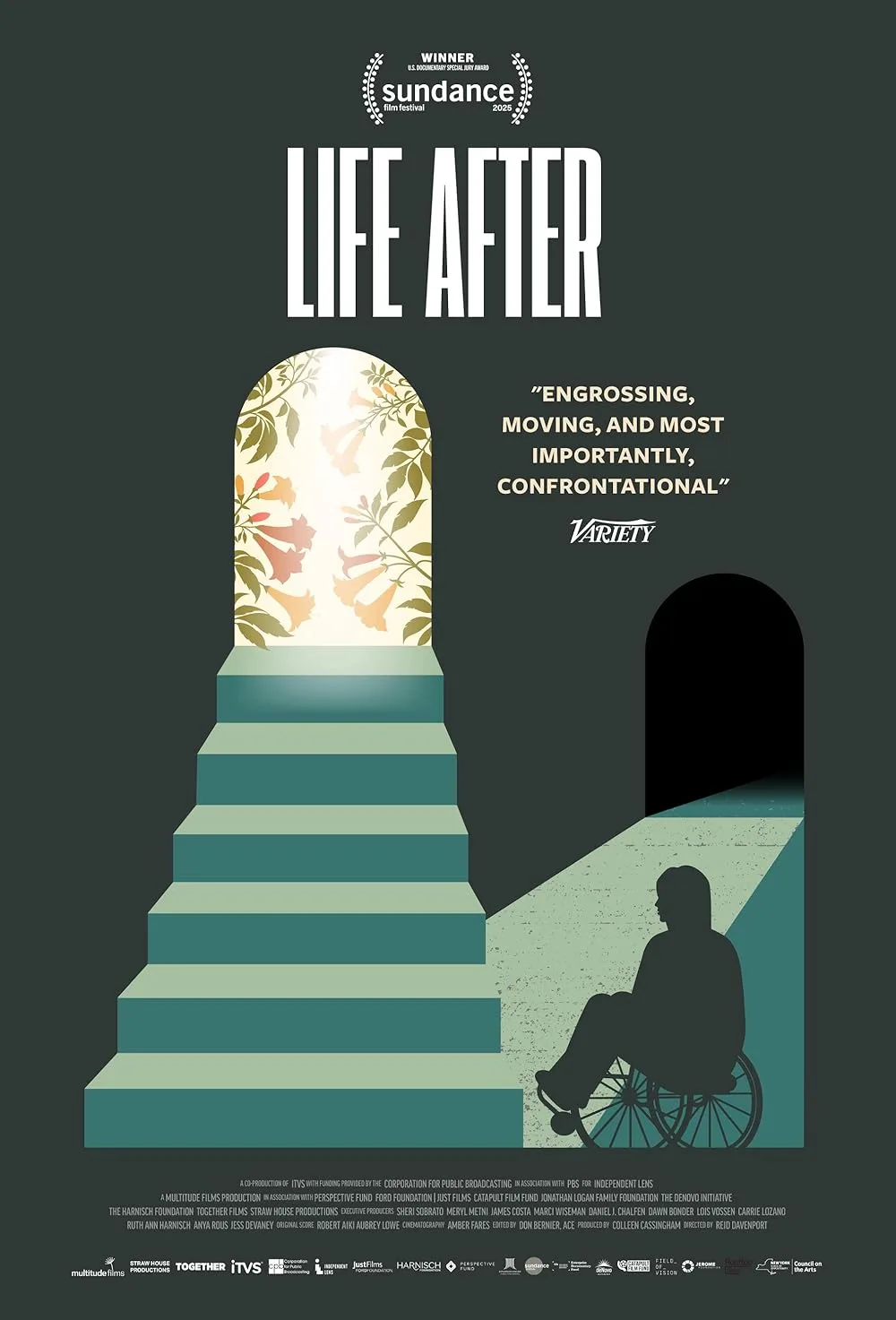

Davenport’s newest work, the documentary “Life After,” expands the radically first-person approach of his last feature, “I Didn’t See You There” (my favorite movie from its release year, 2022), in a way that feels much more traditional. There are techniques borrowed from TV news magazines that are ultimately more of a distraction from the film’s point than a clever means of getting to it, such as Davenport constructing a mystery around the seeming disappearance of a prominent disabled person, Elizabeth Bouvia. Regardless, “Life After” is a powerful movie that examines the political and social structures that surround and control people with disabilities, and comes to a conclusion that will spark many arguments.

The movie begins with footage of Bouvia in the 1980s entering a courtroom in Riverside, California. She’s spent many years in a psychiatric facility because the pain from her cerebral palsy and arthritis was so severe that she couldn’t function, or even move, and wanted the hospital to allow her to starve to death rather than continue living. The hospital force-fed Bouvia. She’s in court with ACLU representation to argue that she has the right to decide whether she will live or die, and that no one else should be able to veto her decision.

Davenport expands out from there, presenting the stories of many disabled people and/or their family and survivors, all of which revolve around some aspect of assisted suicide. Davenport’s unifying focus is a piece of Canadian legislation, C-7, that was passed in 2016. Known as MAID (for Medical Assistance in Dying), the legislation allowed disabled people who had a terminal condition and a rough idea of their future time of death to decide to end their lives rather than endure additional suffering. A 2020 amendment expanded the law’s purview in ways that made it controversial and that are examined in this movie. In the words of an Ottawa politician, it allowed people “to choose a peaceful death if they determined that their situation is no longer tolerable to them, regardless of their proximity to death.”

“I don’t think it’s gonna be a happy ending [for me] unless I control it myself,” Bouvia says in an interview.

You can see from the wording why people would want to argue about the addendum. Their hypotheticals lead to extreme scenarios, like a teenage girl who’s sad about her boyfriend breaking up with her, not merely being legally allowed to end her life but to get the government’s help in doing it. (I didn’t come up with this; it’s part of a news story about MAID that’s partially excerpted in the movie.) But in the end, this sort of talk is a gateway into a wider discussion of moral and political questions that don’t have obvious answers, such as: what is “quality of life”? Do individuals get to decide that without input from any other party? And isn’t right-to-die legislation like MAID a way of encouraging disabled people to end their own lives rather than transform society so that they’re properly supported and taken care of?

That last question is one that Davenport circles throughout the movie. His take is that by encouraging governments to embrace the idea of disabled people ending their own lives instead of suffering additional pain, they are punting on their responsibility to their citizens. It’s expensive and complicated to take care of yourself if you are disabled, or for caregivers to do it for people who can’t do it themselves.

Assisted suicide, Davenport ultimately argues, is a way of not engaging with a much larger problem, which is that disabled people’s lives are not valued like those of abled people, and that some of the support for assisted suicide is coming from the point-of-view of institutions that don’t want to expend time and money on disabled people—and, in some cases, from relatives or mates who are exhausted by their obligations and want out. A disability rights advocate featured in the movie puts it more bluntly: “You can’t address human suffering by killing people.”

One illustration of Davenport’s position is the case of Michael Hixon, an Austin man who in 2017 suffered an anoxic brain injury that made him blind and damaged his spinal cord. The hospital that was treating him wanted to end life-saving measures. There’s a shocking piece of audio in which Hixon’s wife, Melissa, argues with a doctor about the idea of “quality of life.” It becomes clear that the doctor views himself as the representative of a government that believes caring for someone like Hixon is ultimately futile and doesn’t want to “waste” more money on it.

Davenport’s eloquent narration guides us through a thicket of thorny subjects. It’s quite clear by the end how he feels, but the movie leaves room for the viewer to feel some other way. “Life After” is a valuable addition to an emerging canon of work.