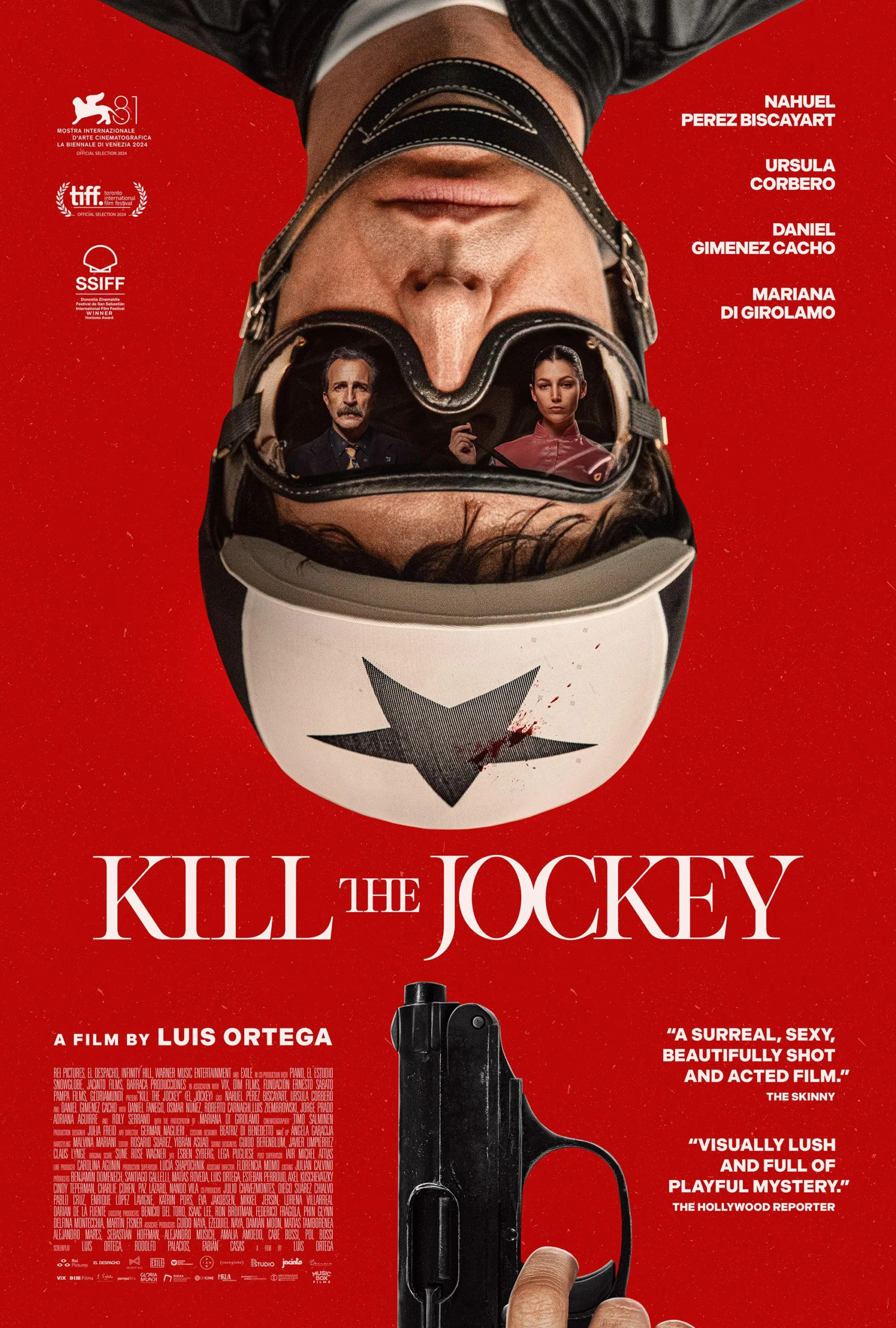

Cigarette smoke is trapped inside a glass where ketamine and liquor swirl around to make a self-destructive cocktail. That concoction, as visually enticing as it is detrimental to the body, encapsulates the essence of “Kill the Jockey,” an intoxicating crime dramedy about one person’s ordeal to live in their true identity. Equal parts sordid and seductive, the latest film by Luis Ortega, the Argentine writer-director of 2018’s “El Angel” (a similarly stylish proposition), plays like a sultry party, the head-splitting hangover, and the cure for it all.

The clandestine mixologist behind that poisonous drink is Remo Manfredini (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart), a famous jockey whose glory days have vanished in a haze of substances and bad decisions. “Misfortune is the best school,” an older henchman says during a dinner with compassion about the childhood trauma that forged Remo into who he is today. He can no longer race sober, so the wealthy man sponsoring him, Sirena (Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho, recently seen in “Bardo”), has taken matters into his own hands to ensure Remo performs in a grand prize event for which he’s bought an expensive Japanese horse.

When not under the cover of sunglasses, Remo’s bulging eyes, even more noticeable because of their heterochromia, seem to always be staring into a distant future, as if plotting to escape his materially successful, yet spiritually unfulfilling life. In what becomes an unexpected, and revelatory dual role, Pérez Biscayart, best known for his lead part in the French queer drama “BPM (Beats Per Minute),” begins “Kill the Jockey” as a wretched man who went right past rock bottom and slowly blossoms into a figure of such enticing poise and luminosity they might be fit for a sensual Pedro Almodóvar entanglement. (Curiously, the Spanish master’s company, El Deseo, produced Ortega’s previous movie.)

At first, Ortega limits the context to the heightened reality we enter, where a sequence set to an electronic tune of female jockeys in sleek outfits stretching before a race feels like an excerpt from a strangely erotic music video. That set piece, intercut with Remo’s descent into the abyss, as well as one showing him dancing with his pregnant wife, Abril (Úrsula Corberó), also a prominent jockey who’s in love with a woman, lends “Kill the Jockey” a delicious, absurdist decadence. Yet, though Ortega’s vision may suggest he’s going for more panache than substance, the theme of self-transformation and even some clarity about how Remo rose and fell from grace emerge unhurriedly.

An actor with an imposing presence, despite his small frame, a magnetic Pérez Biscayart disappears into the character. That kind of full-bodied performance is necessary to play an individual ready to set ablaze nearly every aspect of his existence, except for Abril, in order to obtain freedom. That ravenous desire to be unchained has been present before in Ortega’s work. Whereas in “El Angel,” the young antihero, an innate criminal, exercises his free will to challenge the status quo via bloodshed and mayhem, here Remo must harness violence but for self-liberation. “Kill the Jockey” can itself be described as mischievous, as if the director also wants to test the story’s boundaries of genre and form.

Remo’s internal questioning permeates the other characters in “Kill the Jockey.” Giménez Cacho’s Sirena, an even-headed villain, feels lost when attention for Remo’s drug-related antics hinders his disturbing acts of benevolence. At the same time, Abril finds that romantic love lies elsewhere, even if her affection for Remo remains unwavering. Ortega goes as far as to invite the henchmen into this party of self-reflection about the person the world thinks they are and the way they see themselves. If no one is truly anybody, then everyone has the chance to reinvent themselves, to evolve, to shed one’s old skin and start again anew.

The aesthetic in “Kill the Jockey” might prompt an association with the visual precision of Wes Anderson’s meticulously shot films, including an exquisitely conceived color palette in the costumes and production design. But Ortega’s tone and the deadpan behavior of his droll ensemble, as well as his use of evocative music harnessed for lingering emotional effect, feel closer to those in the work of Yorgos Lanthimos, without entirely reaching for the same bleakness. There’s a farcical charm to Ortega’s latest that reads uniquely Latin American.

The middle section in “Kill the Jockey,” when an injured Remo—in an extravagant coat, a bandaged head, and holding a purse—wanders through Buenos Aires, functions as a period of transition for both the character and the narrative. A deadly turning point gives way to the final portion of the film, which leaves Remo behind and centers on a new protagonist, now fully in the spotlight, whose name is Dolores (or Lola). That’s when Ortega’s surrealist flourishes, which have been present throughout, fully take hold to ponder the possibility of reincarnation.

If the director’s spell has taken hold as presumably intended, by the time the most outlandish touches appear, one has already surrendered to its visceral, chaotic allure.