In my drinking days, some of us would gather around noon on Saturdays at Oxford’s Pub for what we called Drunch. We would commence with shots of creme de menthe and pint glasses of real Coke, in the hope that a combination of alcohol, sugar and caffeine would restore us. Then we would laugh until the tears ran down our faces about the hilarity of the dreadful things that had happened the night before. In doing this, I would often quote “We laugh, that we may not cry,” although just now I have discovered that no one originally said that. I always thought it was Shakespeare. It was me.

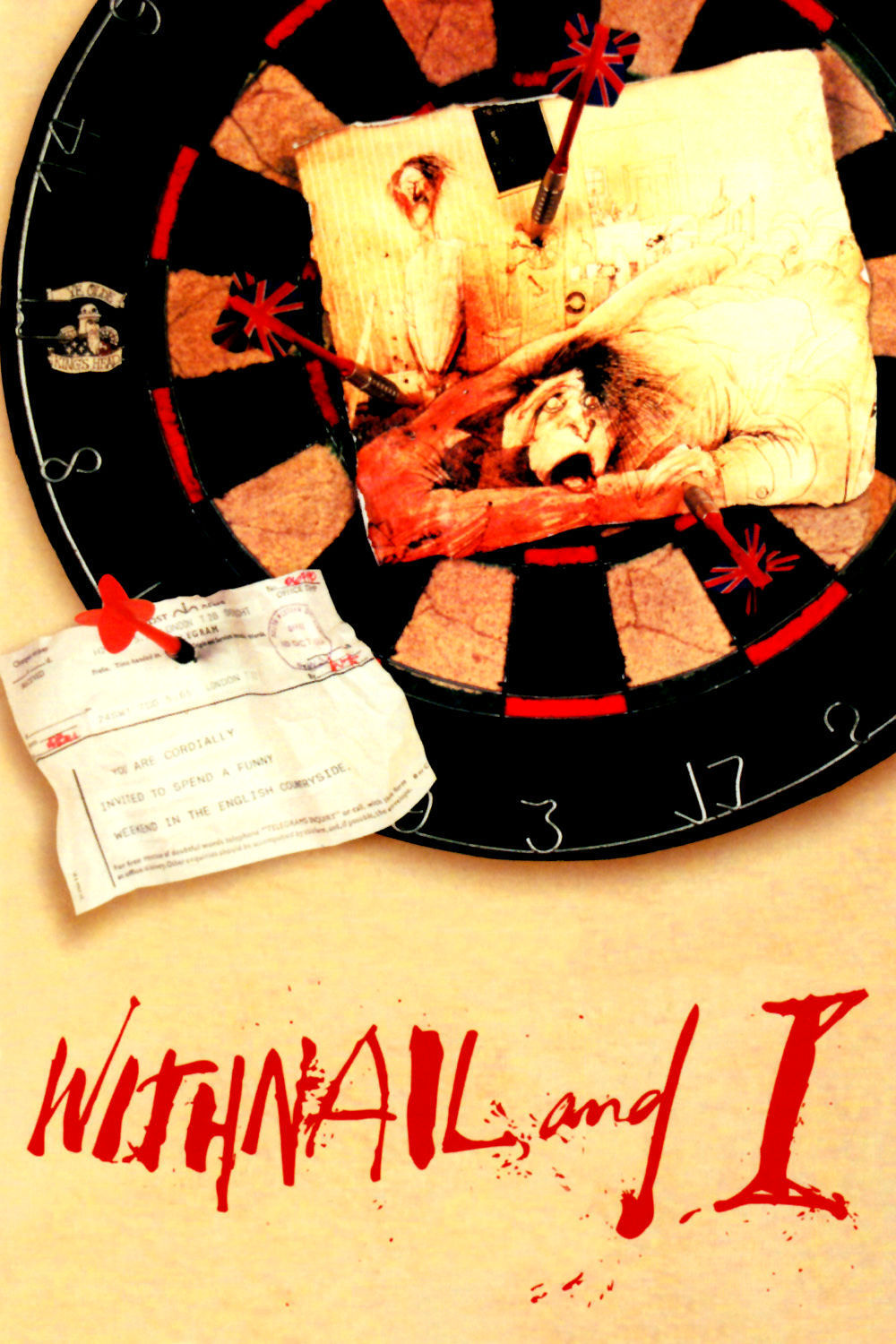

I relate this story to explain why I identify with “Withnail & I” (1987), which conveys the experience of being drunk so well that the only way I could improve upon it would be to stand behind you and hammer your head with two-pound bags of frozen peas. It is said that Bruce Robinson, the film’s writer and director, based it largely on his friendship in the 1960s with Vivian MacKerrell, a usually unemployed actor and full-time alcoholic. They shared lodgings and misery in London, where Robinson recalls being down to one light bulb and taking it with him from room to room. The critic Mark Morris, in an article titled “The real Withnail,” writes:

“Robinson knew it had to end when MacKerrell returned from a trip home to Scotland armed with bottles of a drink — 200 percent proof, Robinson claims — that distillery workers made by sticking used whiskey filters into spin driers. Deranged by the drink, Robinson and MacKerrell, armed with a hammer and an artificial leg, smashed down one of the walls of their house. It still took another six months for Robinson and MacKerrell to work up the will go their separate ways.”

In the film as in life, Withnail and “I” live in poverty and disarray and do not waste valuable drinking time by doing anything else. Since drink costs money, and Withnail (Richard E. Grant) can be quick to order “four quadruple whiskeys and a couple of pints,” there is the presumption that he receives funds from his well-off homosexual uncle Montague Withnail (Richard Griffiths). It is to Uncle Monty that they appeal for the loan of his country cottage, when they are seized by the need for a change of scene. Perhaps they are seeking a geographical cure.

Robinson based the character of “I” on himself. Students of the film have learned from one glimpse of a telegram that the character’s name is Marwood; it never appears in the dialogue. Marwood has within himself the seeds of sanity and prudence. He drinks heavily, but Withnail is consumed by an unslakable thirst. Withnail is also possessed by fury. He is angry at everyone and everything almost all the time, except when a brief window sometimes opens between his last hangover and his next binge. He drops the f-bomb as punctuation, and his face reveals bitter resentment. What does he resent? That the world and everyone in it, except possibly Marwood, have conspired to make his life miserable.

The performance by Richard E. Grant is a tour de force. “Withnail & I” was his second film. IMDb lists 76 other credits, but it is his destiny to be forever linked with this early role that has become iconic. To this day there must be those who imagine Grant himself to be hostile and furious, yet in person, he is just another talented acting bloke. Withnail could possibly have become a comic drunk in the wrong hands. Richard E. Grant never, ever, not for a second, breaks character; he is relentlessly wounded and aggressive. He never goes too far, he never relaxes, he aims at the end of the movie and charges.

Paul McGann, as Marwood, reflects a tenuous grip on reality. And he makes the right choices in the role; he doesn’t play a straight man or a sparring partner, but a fellow trekker on a daily journey to oblivion. He retains shreds of common sense. When Withnail snatches a can of lighter fluid and squirts in down his throat, Marwood is horrified. When Withnail starts looking for antifreeze, Marwood cries out: “Don’t mix your drinks!” Incredibly, not even this scene is invented; Vivian MacKerrell did drink lighter fluid and went blind for several days; Robinson thinks that may have contributed to his death from throat cancer at 51. That, and his smoking. Withnail smokes as if his cigarette is the source of life.

Their sojourn in the country cottage is the centerpiece. They are hopelessly inadequate for such tasks as building a fire and cooking, and our last sight of a rooster being placed in the oven is not one we shall soon forget. They have difficulties with the locals, including the poacher who is accused by Withnail in a pub: “You’ve got an eel down your leg!”

Uncle Monty comes to visit and grows amorous toward Marwood: “I mean to have you even if it must be burglary!” Robinson says this advance was inspired by the romantic overtures of Franco Zeffirelli when he was playing Benvolio in his “Romeo and Juliet.” Richard Griffith is wonderful in the role, plummy and insinuating, self-effacing in an affected way. (Withnail says, “Monty used to act,” and he replies: “I’d hardly say that. It’s true I crept the boards in my youth, but I never had it in my blood.”)

The dialogue is famous and quoted; in the U.K., certain lines are widely recognized. “I can’t get my boots on when they’re hot,” “Those are the kind of windows faces look in at,” “Warm up? We may as well sit round this cigarette,” “My thumbs have gone weird!” and Danny the drug dealer’s “Hairs are your aerials. They pick up signals from the cosmos and transmit them directly into the brain. This is the reason bald-headed men are uptight.”

Danny (Ralph Brown) has dialogue that speaks to the bottom line of the movie: “We are 91 days away from the end of the 1960s, the greatest decade in human history.” The film is a time capsule, not least because booze is more central than drugs, although Danny’s theory of the politics of uppers and downers is prophetic. Withnail and Marwood share the delusion that release and elation can be found in a bottle. If you asked them if it made them happy to drink, they would probably claim that it did, and that’s why they do it.

Well, maybe not Withnail. For reasons remaining obscure and certainly never mentioned by him, he seems to be courting suicide. He pours bottles down his throat, sucks on cigarettes, alienates the world, always looks enraged. At the end of the film, he has a famous scene when he stands in the rain beside a fence and performs the Hamlet soliloquy including, “What a piece of work is a man!” He is one of the rare characters in modern films who can quote it with accuracy about himself.

That scene reflects on a quality in the film: Withnail, Marwood and Monty for that matter, are well educated, steeped in literature and drama, and so their speech is not sodden but shows intelligence and wit even in the worst of times. (Marwood, after being threatened by a man in a pub: “I don’t consciously offend big men like this. And this one has a decided imbalance of hormone in him. Get any more masculine than that and you’d have to live up a tree.”)

Why does the film, which I have made sound so depressing, remain so popular after more than 20 years? It achieves a kind of transcendence in its gloom. It is uncompromisingly, sincerely, itself. It is not a lesson or a lecture, it is funny but in a consistent way that it earns, and it is unforgettably acted. Bruce Robinson saw such times, survived them and remembers them not with bitterness but fidelity. In Withnail, he creates one of the iconic figures in modern films. Most of us may have known someone like Withnail. It is likely that Withnail never knew someone like us. His mind was elsewhere.