Turkish filmmaker Nuri Blige Ceylan is undeniably a world-class filmmaker, but he does not, as they say, crush it every time up. To go back a few films, his 2006 “Climates” was a moody and mordantly funny relationship sulk; his 2008 domestic drama “Three Monkeys” was too impressed by its allegorical leanings; his 2011 “Once Upon A Time In Anatolia,” while searing, also felt a little too self-consciously ambitious. The running time of his new picture “Winter Sleep,” three hours and change, suggests a similar weight, but at it happens, this movie struck me as both Ceylan’s plainest, and perhaps his finest.

On its surface, “Winter Sleep” seems to partake, if not indulge, a familiar European art-film staple, placing a male protagonist in various forms of isolation/alienation from relatives and friends as he and they discuss burning issues of philosophy and emotion. Ceylan invokes/evokes Chekhov in his scenario: protagonist Aydin, an aging former theatrical actor, runs a hotel in a picturesque section of Anatolia and desultorily deals with surly tenants on some land he owns, a disenchanted (and much younger) wife, a watchful sister, and various others, revealing the discontents at the roots of all their relationship and a deep dissatisfaction with life itself, despite the prestige and autonomy and leisure that Aydin enjoys.

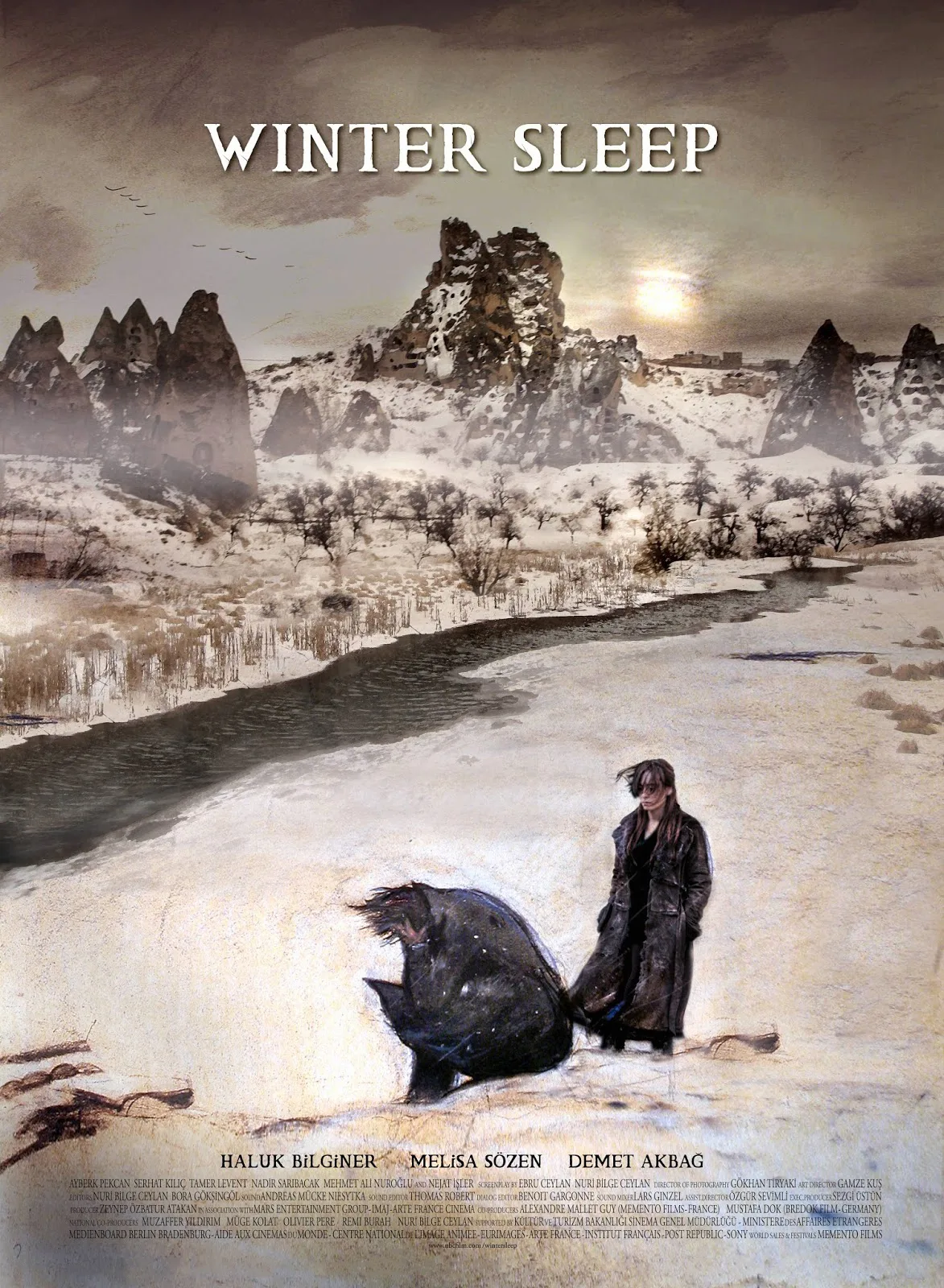

The movie, which won the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, has been disparaged by some skeptical critics as a gabfest, and it’s true, there’s a lot of talk here, and very little of it’s small. But that’s not to say that the film is glacially paced; even when staying in the same settings, Ceylan’s camerawork and editing are terrifically alert. The talk, for all its abstractions, gradually lays bare the poor regard with which most of the characters hold each other, and, at about the halfway point, when Aydin (played with glum tenacity by Haluk Bilginer) calls his put-upon spouse (Melisa Sözen) a “bored neurotic,” the fur really begins to fly. Not much of what is said by these characters is particularly novel or earth-shaking it’s true, but I think that’s central to what Ceylan is doing here. This is a work of cinema, not theater or prose, and what counts most in “Winter Sleep,” to me at least, is not the commonplace sentiments of dysfunction and dread, but spaces between the words. The accumulation of images imbues the film with a kind of bleak coziness that brings to life the accusation that Aydin’s sister Necia (Demet Akbag) levels at him: “In order not to suffer, you prefer to fool yourself.”

The strength of “Winter Sleep” is not so much in what any of the characters say as much as what it needs its near-monumental length to actually show: which is the way the most seemingly banal circumstances can throw you into a dark night of the soul before you even know what’s going on, a state of wide-awake despair so calamitous one has no choice but to make a companion of it. That sounds like a paradoxical state—and it is, a painfully paradoxical one, but it’s a real one, and the signal accomplishment of “Winter Sleep” is that Ceylan’s empathy and technical facility make it palpable in the artistic realm. It’s a daunting achievement and in a strange way also a comfort.